Heidi Stevens: A son's death and a father's loving determination to keep his true, unvarnished story alive

Published in Lifestyles

This will be Craig and Donna Mindrum’s first Christmas without their son Jonathan. He died in January at age 36, leaving their family with a gaping wound where a son and a brother and an uncle should be.

Nothing will fill it, but time and talking may help it heal, Craig Mindrum figures. Hopes.

“It’s got to get better,” he said a few days after Thanksgiving. “I trust people who tell me it does get better.”

Thanksgiving was hard.

“Thank God for football,” he said. “You sort of go back and forth between needing people and not wanting to be around people. At least I could watch the Bears lose.”

(There’s comfort in consistency.)

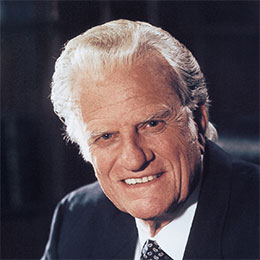

Mindrum is a writer and a teacher and a thinker. He earned master’s degrees at Yale Divinity School and Indiana University. He has a Ph.D. from University of Chicago Divinity School. We connected a couple years ago about writing and have followed each other’s lives through social media. I’m often inspired and moved by the way he processes life’s moments, big and small.

When Jonathan died, Mindrum shared his grief publicly. Generously, I would say. It’s such a bewildering, lonely, unspeakable thing to lose a child and when someone finds a way to speak about it anyway, I am humbled and awed — by their willingness to share such a profound ache with other people, by their courage to ask for and receive comfort from other people, even people who have no earthly idea what it feels like to ache that deeply.

In November, Mindrum wrote about Jonathan’s death in Newsweek.

“On January 24, 2024, my son was having a blast on the dance floor of a Caribbean cruise ship — without warning, he collapsed and died,” Mindrum wrote. “Efforts to revive him were futile. Narcan did nothing, so we presume fentanyl or other opioids were not involved — an MDMA (Molly) probably so.”

Results from the autopsy are still pending.

“Maybe I should be embarrassed or think it scandalous to admit he died from recreational drugs,” he continued, “but that's not how I feel.”

How he feels is that his son was a brilliant, loyal guy who, despite being born more than two months prematurely and weighing in at just 3 pounds that momentous, terrifying day, lived a huge life.

“Jonathan was among the smartest people I ever knew,” Mindrum said in his son’s eulogy. “Tell him news about astronomers discovering a planet light years away that seemed conducive to supporting life and he would give you 20 minutes on it. Talk about the complexities of the Ukraine war and he’d give you 20 minutes.”

Mindrum would give anything for 20 more of those minutes. Instead, he’ll settle for making sure Jonathan is known and remembered exactly as he was — the way he lived, the way he died, and everything in between.

“Close to a year after, I’ll still be writing something or reading something and I’ll think, ‘I gotta ask Jonathan about that,’” Mindrum said. “It’s always kind of a punch in the face. But I’m also glad. I’m glad I retain that impulse.”

It keeps Jonathan close by. So does talking about him. He hopes his friends never stop asking about Jonathan or sharing stories about Jonathan. That’s so much more helpful, he said, than explanations.

“If someone says to me, ‘He's with God now’ or ‘God called him home,’ that's unhelpful,” Mindrum said. “I don't believe in that kind of God.”

He wrote in Newsweek: “My academicized theology does not hold with a God who numbers the hairs on our heads or is aware of the fall of a sparrow — no Santa Claus God who rewards and punishes us according to our beliefs and actions. God did not cause or allow my son to die.”

He does believe this:

“We create and fashion meaning as we live,” he said. “The question is not finding a reason for your loved one's death, but creating meaning in the wake of that tragedy. We are fashioning meaning as if we were working in clay.”

I think I'll carry that image with me forever.

It felt important to me to tell a little bit of Jonathan’s story, a little bit of his dad’s story, as we head into Christmas. So much of what we share this time of year is joyful and saccharine and polished to the point of glittering. That’s beautiful and important, but it’s not everyone’s story. It’s certainly not everyone’s whole story.

And whole stories, true stories, connect us.

“Healing,” bell hooks wrote, “is an act of communion, and rarely, if ever, are people healed in isolation.”

©2024 Tribune News Service. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments