Airdropping vaccines to eliminate canine rabies in Texas – two scientists explain the decades of research behind its success

Published in Health & Fitness

Rabies is a deadly disease. Without vaccination, a rabies infection is nearly 100% fatal once someone develops symptoms. Texas has experienced two rabies epidemics in animals since 1988: one involving coyotes and dogs in south Texas, and the other involving gray foxes in west central Texas. Affecting 74 counties, these outbreaks led to thousands of people who could have been exposed, two human deaths and countless animal lives lost.

In 1994, Gov. Ann Richards declared rabies a state health emergency. The Texas Department of State Health Services responded by launching the Oral Rabies Vaccination Program to control the spread of these wildlife rabies outbreaks.

Since 1995, the program has distributed over 53 million doses of rabies vaccine over 758,100 square miles (nearly 2 million square kilometers) in Texas by hand or aircraft. Rabies cases in dogs and coyotes went from 141 to 0 by 2005, and rabies cases in foxes went from 101 to 0 by 2014. By 2004, one canine rabies variant was effectively eliminated from Texas, and another variant was substantially controlled.

We are researchers who began studying wildlife rabies and oral vaccination in the 1980s. From providing a proof of concept in using oral vaccines in raccoons to being among the first to use new rabies vaccines in the 1990s, we were on the ground floor of efforts to contain this deadly virus.

Decades of vaccine research led to one of the most successful public health projects in Texas. And we’re hopeful it could provide a road map for the use of mass wildlife vaccination to prevent future outbreaks.

The Texas Oral Rabies Vaccination Program benefited greatly from the work of multiple researchers over prior decades.

The mid-20th century saw several major developments in rabies control. With the failure of efforts to poison or trap infected animals, virologist and veterinarian George Baer at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognized the need for a different strategy to prevent and control wildlife rabies. His and his colleagues’ work in the 1960s led to the concept of oral rabies vaccination. While orally vaccinating wildlife would help combat infection at its source, it was previously thought to be logistically unfeasible given the large range of target animals.

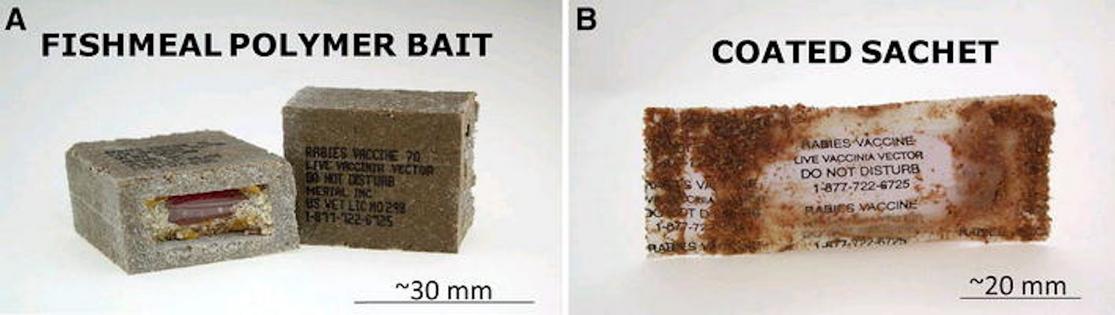

By the late 1970s, European researchers began the first field trials to orally vaccinate foxes against rabies. Small plastic containers were filled with vaccines and placed into baits, such as chicken heads. Over 50,000 of these vaccine-laden baits were distributed over four years in fox habitats in forests and fields.

Researchers in Canada also began similar field trials in Ontario. During the 1980s, an average of 235 rabid foxes per year were reported in the area. Baits containing oral rabies vaccine were dropped annually from 1989 to 1995 and successfully eliminated the fox variant of rabies from the whole area.

The first generation of these vaccines used live viruses modified in an attempt to not cause severe disease. Although effective and generally safe, the original rabies vaccines had to be kept in cool temperatures and had the rare risk of causing rabies in animals.

In the early 1980s, scientists developed recombinant rabies vaccines, which use a separate virus to express the genes of the rabies virus. A collaboration between a nonprofit institute, the U.S. government, and the pharmaceutical industry led to the development of a recombinant viral vaccine that produced a rapid immune response against rabies without the possibility of causing rabies.

In 1984, preliminary work in laboratory animals showed the promise of using an oral form of the recombinant vaccine to vaccinate animals. However, the concept of using genetically modified organisms was in its infancy among both scientists and the general public. While the vaccine was safe and effective in captive raccoons and foxes, major questions loomed over how it might affect other species once released into the environment.

After years of work improving the vaccine’s design and testing its safety in several nonhuman species, the first European trial was held on a military base in Belgium. With data supporting it could safely and effectively control wildlife in Luxembourg and France, the vaccine was licensed to control fox rabies in 1995.

In the U.S., similar studies of the oral recombinant rabies vaccine were conducted. The first trial began in 1990 at Parramore Island off the Virginia coast, and a year of intensive monitoring found no significant adverse effects on the environment or any wildlife species. A second yearlong study on the mainland near Williamsport, Pennsylvania, had similarly positive results.

After the vaccine was successfully used to control raccoon rabies in tests in several other East Coast states, it was approved for use on raccoons in 1997.

In 1998, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service received funding to expand existing oral wildlife vaccination projects to states of strategic importance, to prevent the spread of specific rabies viruses, and to coordinate interstate projects.

In Texas, the oral recombinant vaccine is now primarily distributed by hand and by approximately 75 separate helicopter flights annually.

The Texas Department of State Health Services rabies laboratory worked alongside the CDC to create the Regional Rabies Virus Reference Typing Laboratory. One of us was recruited to both distribute the vaccine in the field and to develop molecular typing tools to discriminate between different types of rabies virus variants in the lab. These techniques allowed us to identify where different rabies virus variants were emerging at any given moment.

Our lab was also the first in the nation outside of the CDC to assist other U.S. states and countries in testing their specimens for rabies virus variants. These techniques helped researchers monitor where the rabies epizootic was ongoing or retreating due to wildlife vaccination and new forms of spread.

With the constant threat of emerging and reemerging infectious diseases like COVID-19 and influenza, the prospect of mass vaccination of wild animals may be one way to address future pandemics. Though there is much work ahead of us, we have hope that we may one day have the option of using mass wildlife vaccination to reduce or eliminate infectious diseases like rabies.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Rodney E. Rohde, Texas State University and Charles Rupprecht, Auburn University

Read more:

Rabies is an ancient, unpredictable and potentially fatal disease − two rabies researchers explain how to protect yourself

In the rare event of a vaccine injury, Australians should be compensated

‘Vaccinating’ frogs may or may not protect them against a pandemic – but it does provide another option for conservation

Rodney E. Rohde has received funding from the American Society of Clinical Pathologists, American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science, U.S. Department of Labor (OSHA), and other public and private entities/foundations. Rohde is affiliated with ASCP, ASCLS, ASM, and serves on several scientific advisory boards.

Charles E. Rupprecht consults for global academic, governmental, industrial and NGO organizations. He receives funding from academic, governmental, industrial, and NGO sources.

Comments