Fungal infections known as valley fever could spike this fall - 3 epidemiologists explain how to protect yourself

Published in Health & Fitness

As the climate warms, the southwestern U.S. is increasingly experiencing weather whiplash as the region swings from drought to flooding and back again. As a result, the public is hearing more about little-known infectious diseases, such as valley fever.

In May 2024, about 20,000 people attended a music festival in Buena Vista Lake, California. In the months that followed, at least 19 developed valley fever, and eight were hospitalized from their infection. This outbreak follows a dramatic increase of more than 800% in valley fever infections in California between 2000 and 2018.

In 2023, California reported the second-highest number of valley fever cases on record, with more than 9,000 cases reported statewide. And between April 2023 and March 2024, California provisionally reported 10,593 cases – 40% more than during the same period the prior year.

The Conversation U.S. asked Jennifer Head, Simon Camponuri and Alexandra Heaney – researchers specializing in the epidemiology of valley fever – to explain what valley fever is, and what might explain its rise in recent years.

Valley fever is the common name for a disease called coccidioidomycosis, which is an infection caused by pathogenic fungi from the Coccidioides genus. The fungi are primarily found in arid soils of the southwestern United States, as well as parts of Central and South America.

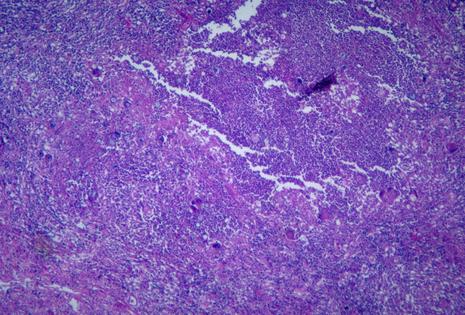

When the fungus has access to moisture and nutrients, it grows long, branching fungal chains throughout the soil. When the soil dries out, these chains fragment to form fungal spores, which can be stirred up into the air when the soil is disturbed, such as by wind or digging. Airborne spores can then be inhaled and cause a respiratory infection.

Cases of valley fever are typically highest in California’s southern San Joaquin Valley and southern Arizona, but they have been increasing outside of these regions. Between 2000 and 2018, the incidence of valley fever cases increased fifteenfold in the northern San Joaquin Valley and eightfold along the Southern California coast. And between 2014 and 2018, incidence increased by more than eightfold along the central coast.

Because of these trends and the virulence of the pathogen that causes valley fever, it is listed as a priority pathogen by the World Health Organization. Historically, fungal infections have received very little attention and resources. By creating this list, the WHO is hoping to galvanize action surrounding listed pathogens, including getting more resources for research as well as the development of new treatments.

After inhaling fungal spores from the environment, Coccidioides initially infects the lungs, causing symptoms like mild to severe cough, fever, difficulty breathing, chest pain and tiredness. Valley fever symptoms can resemble other common respiratory infections, so it’s important for people to get checked by a doctor if they’ve experienced prolonged symptoms, particularly if they have been given antibiotics that they are not responding to.

In California and Arizona, an estimated one-third of community-acquired pneumonia cases – or pneumonia acquired outside of the hospital – are caused by valley fever. However, only a fraction of community-acquired pneumonia cases get tested for it, so it’s likely the number of valley fever cases is significantly higher. Among diagnosed cases, half experienced symptoms for two months or more before being diagnosed.

In 5% to 10% of cases, the fungus can spread from the lungs to other parts of the body, such as the central nervous system, liver and bones, causing meningitis or arthritis-like symptoms. These cases can be severe and possibly fatal.

Antifungal treatment is available, and early diagnosis and treatment is critical for better outcomes.

Valley fever cases can occur year-round, but in California, cases reported via surveillance systems tend to increase starting in August and September, peak in November and return to background levels in January and February.

Researchers believe that patients are likely exposed to the fungus in the summer and early fall months, typically one to three months prior to their diagnosis. This delay accounts for time between when patients are exposed, develop symptoms and are diagnosed with the disease. While cases peak in the fall on average, seasonal strength and timing varies regionally.

Our research shows that this seasonal surge in the fall is especially strong following wetter winters and that alternation between dry and wet conditions is associated with increased incidence in fall months.

Valley fever cases in California nearly doubled following wet winters that occurred one and two years after the 2007-2009 and 2012-2015 droughts.

In 2023, California experienced a similar transition, with an extreme drought occurring between 2020-2022 followed by heavy precipitation in the winter of 2022-2023.

This transition was followed by a near-record spike in cases in 2023. The state experienced another wet winter during the 2023-2024 wet season, furthering concern about continued high risk for valley fever in 2024.

Our research team recently developed a model to forecast valley fever cases that will occur between April 2024 and March 2025 in California. We forecast that the state is likely to see another spike in cases during the fall and winter of 2024, on par with the spike in 2023.

During high-risk periods, clinicians should consider valley fever as a potential diagnosis. This is especially true when evaluating a patient presenting with valley fever symptoms or a respiratory illness who lives in, works in or traveled to an endemic or emerging region.

We are currently working to characterize seasonal disease patterns in Arizona as well, which are different from California’s. This is likely because Arizona has two rainy seasons.

Those who spend time or work outdoors in areas where valley fever is common, especially where they may be exposed to dirt and dust, are more likely to get it.

While healthy people are still at risk of infection, certain factors can increase the likelihood of developing severe disease from valley fever. These include being an adult 60 years or older, having diabetes, HIV or another condition that weakens the immune system, or being pregnant. People who are Black or Filipino also have been noted to have a higher risk of severe disease, which may relate to more exposure to the fungal spores, underlying health conditions, inequities in accessing care or other possible predispositions.

People who live and work in the regions where the fungus is found should avoid exposure to dust as much as possible. When it is windy outside and the air is dusty, stay indoors and keep windows and doors closed.

When driving through a dusty area, limit vehicle speed, keep car windows closed and recirculate the air, if possible. When working outdoors, use dust suppression techniques, including wetting soil before digging to prevent stirring up dust, and installing fencing, windbreaks and vegetation where possible.

For those who must directly stir up soil or be in dusty conditions, such as while doing construction or gardening work, consider using an N95 mask to limit dust inhalation.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jennifer Head, University of Michigan; Alexandra K. Heaney, University of California, San Diego, and Simon Camponuri, University of California, Berkeley

Read more:

A new hybrid fungus is found in hospitals and linked to lung disease

Drilling down on treatment-resistant fungi with molecular machines

Banana apocalypse, part 2 – a genomicist explains the tricky genetics of the fungus devastating bananas worldwide

Jennifer Head receives funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health.

Alexandra K. Heaney receives funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health.

Simon Camponuri receives funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health and from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Comments