Mark Gongloff: California fires expose a $1 trillion hole in US home insurance

Published in Business News

The wildfires terrorizing Los Angeles this week have been like something out of a movie: vast, fast-moving, unpredictable, merciless. Their scope and nature have surprised even fire-jaded California.

They are also evidence of the sort of consequences that can be expected as the planet continues to heat up, consequences for which traditional risk-management tools — like, say, home insurance — are increasingly obsolete.

The fires didn’t even exist on Tuesday morning. The only hint of what was to come were forecasts for some of the strongest and most dangerous Santa Ana winds on record to barrel out of the Great Basin and into Southern California. Those hurricane-force blasts can be destructive enough.

But these coincided with drought conditions, dry vegetation, low humidity and relatively high air temperatures, leading the National Weather Service to issue an “extremely critical” fire-weather warning for the area around Los Angeles, the first-ever such warning in the lower 48 U.S. states in January.

It didn’t take long to see the results. Within hours, a serious fire was threatening the Pacific Palisades neighborhood in western Los Angeles, moving so quickly that some residents abandoned their cars on the road and fled by foot.

By Wednesday morning, three out-of-control fires had spread across 4,500 acres around the city, taking at least two lives and destroying at least 100 buildings and threatening hundreds of thousands of people and tens of thousands of homes and businesses. And the emergency had not yet peaked, with strong winds expected to continue the rest of the week.

There have always been Santa Ana winds and wildfires in California. But climate change, along with human development, has made the combination of the two much more destructive. Warmer air dumps more moisture when it rains and snows, which encourages plant life in the spring. But then all those plants become kindling during hot, bone-dry summers and falls. When the Santa Ana winds blow down through the canyons out of the Great Basin in the colder months, all it takes is a spark to create a monster fire that spreads quickly.

And those fires generate new sparks, spreading fires across landscapes that over the past few decades have been filled with houses. These structures, built in what’s known as the wildlife-urban interface, become their own kindling, as Tim Sahay, co-director of the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab, pointed out on Bluesky.

The glut of homes in increasingly fire-prone places has created an insurance crisis in California, with many big insurers pulling out of the state to avoid more losses. Nearly 500,000 Californians have turned to the state’s insurer of last resort, the FAIR Plan, which has doubled in size over the past five years. The state is now exposed to nearly $458 billion in potential damage, a figure that has nearly tripled since 2020.

The neighborhoods in the path of the Palisades and other fires burning this week have been among some of the hardest-hit by insurer defections in recent years. The 90272 ZIP code of Pacific Palisades experienced 1,930 policy non-renewals between 2019 and 2024, according to a San Francisco Chronicle tally, or 28 out of every 100 policies.

Pacific Palisades is also the state’s fifth-largest user of FAIR policies, with nearly $6 billion in exposure. Even a fraction of that amount would exceed the capabilities of FAIR, which at last report had about $700 million in cash. Additional damage can be passed on to private insurers, which would pass those costs immediately to their less-risky customers.

California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara last month announced policy tweaks to encourage insurers to come back to the state. They can now use catastrophe modeling to set rates after long being required to consider only historic losses. But part of their modeling must also include fire-defense measures property owners take. Insurers can also now pass the cost of reinsurance on to their customers. Providers lured back to the state by these incentives must cover risky areas at a rate of 85% of their statewide market share.

The aim of such reforms is to boost the availability of private insurance, keep it affordable and improve the adequacy of coverage — the three “A’s,” as Kenneth Klein, a professor at California Western School of Law in San Diego, puts it. He suggests the new regulations will probably help with availability, but they definitely won’t help with affordability; insurers will raise rates, and they’ll be using black-box models to do so.

Private insurance plans will be more adequate, meaning they will cover more damage, than the FAIR Plan. They are typically “replacement cost value” plans, compared with FAIR’s “actual cash value” plans. But even private insurance plans aren’t always enough to fully reimburse a homeowner, given rising rebuilding costs, especially after a widespread disaster. Klein has suggested 80% of Americans don’t have enough home insurance.

“People buying from private insurers will think they have full and adequate insurance. Their insurer may even think that,” Klein said. “Most of them will not have that, and they’ll never know it because they’ll never have their home destroyed.”

This isn’t just a California problem. Other states on the front lines of climate change are underinsured for fires, floods, hurricanes and other disasters that are becoming more frequent or intense or both as the planet warms. There may be more than $1 trillion in hidden home-value losses from floods and fires alone, posing the threat of a mini financial crisis.

Florida and many other states have their own insurance crises, which they have managed to varying degrees of failure. Many homeowners in these places are turning not only to state insurers but lightly regulated insurers, taking on even more risk for themselves and ultimately taxpayers.

At some point, policymakers and the people living in risky places will have to decide when enough is enough. How many times should we pay to rebuild a home on a wildfire-prone California hillside or a flood-prone North Carolina beach? How many first responders’ lives are worth risking so people can have beautiful views? When does insurance become a Band-Aid on a gushing wound?

The first, best thing we can do is stop burning the fossil fuels that are heating the planet and making the problem worse. Until then, homeowners should understand just how much insurance coverage they truly need and react accordingly. It is possible to build fire- and flood-resistant structures, but can you afford them?

Policymakers need to decide when to let the rising seas or expanding deserts take over land where people used to be and build new, affordable housing for those people in safer areas. This will involve reorganizing how society thinks about property risk. But if we don’t start that process now, it will be forced on us, probably when we least expect it.

_____

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

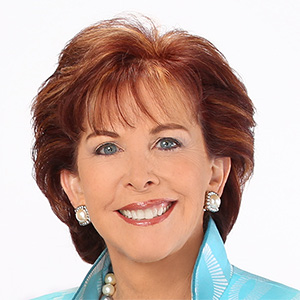

Mark Gongloff is a Bloomberg Opinion editor and columnist covering climate change. He previously worked for Fortune.com, the Huffington Post and the Wall Street Journal.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg News. Visit at bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments