Miamians are the most rent-burdened people in America -- and they're stressed about it

Published in Business News

Their budgets strained, Miami metro residents are distressed about life in their increasingly unaffordable community.

More than three-quarters of South Floridians report difficulty paying for usual household expenses, according to the Census Bureau’s newest Household Pulse Survey released on Thursday.

That makes greater Miami — which encompasses Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties — one of the most financially stretched metropolitan areas in the country, surpassing even notoriously costly cities like New York City, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

According to the survey, 76% of people in greater Miami — the second-highest rate in any major metro area in the nation and just one percentage point behind the beleaguered Dallasites — are at least moderately stressed about rising costs where they live.

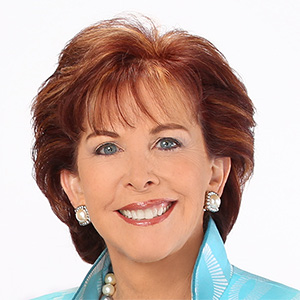

Stephania Germain is one of those people. A 24-year-old single mother and program associate at the affordable housing nonprofit Miami Homes for All, Germain, like many of her stressed-out neighbors, points to rising rents as a primary cause of her financial woes.

For her one-bedroom apartment in Miami Lakes, which Germain shares with her 17-month-old daughter, rent is $1,320. Come Nov. 1, it’ll be $2,072.

Even with the Section 8 housing assistance that covers the bulk of her rent, almost a third of Germain’s salary will go toward housing.

Germain is “cost-burdened,” a Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) term for people who spend at least 30% of their monthly income on housing.

It’s an attribute Germain shares with almost 60% of renters in greater Miami, the most cost-burdened major metropolitan area in the country, per the Census Bureau’s 2023 American Communities Survey, its most recent such report. Nearly a third of renters in the Miami area are severely cost-burdened, meaning they spend at least half of their monthly income on housing.

Miami homeowners with mortgages fare a bit better — 42% are cost-burdened — though they still spend a greater portion of their incomes on housing than their counterparts in every major American metro region.

General inflation in recent years has contributed to that squeeze. But while price changes have largely stabilized, wages haven’t caught up, said David Altig, executive vice president and chief policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, whose purview includes Florida.

Diminished purchasing power, particularly for Miami’s middle- and lower-income residents, has coincided with a rise in local rent costs.

Thanks in large part to an influx of out-of-state high-income earners, local real estate prices went through the roof during and since the pandemic, noted David Andolfatto, chair of the economics department at the University of Miami.

“The cost of living has gone up very rapidly, and rent, particularly in Miami, has gone up dramatically,” he said.

HUD tracks what it considers to be fair market rents across the country. The department estimates that the average monthly rent of a two-bedroom apartment in the Miami area has risen more than 21% — from $1,923 to $2,324 — since last year. No major American metro area has seen such a steep rise.

In Atlanta, which saw the second-highest rent spike in the U.S., the average monthly cost of a two-bedroom apartment jumped 18%.

As she emptied $171 worth of loose change into a coin collector at her local Publix, Johanna Villafranca, a Flagami resident, shared that her rent jumped more than 50% this year.

The mother of six estimates that her household spends half of its income on the $2,300 monthly rent — sometimes more, depending on how much her husband, who works in construction, and her adult children make.

In order to pay rent, Villafranca has shelved necessary repairs for her car, including a new battery. “I can’t fix my car, pay rent and pay for food,” she said.

Germain has also had to make serious spending cuts after the rent hike.

“I can’t buy my baby no clothes. … I can’t buy her shoes,” she said, her voice harried and quickening as she lamented her daughter’s wardrobe, which is fit for a child half her age. Germain’s budget is almost entirely nondiscretionary, and her ability to save is nonexistent.

Though she is grateful for it, Germain wants to be able to live without the government assistance she receives. But because of rising housing costs across South Florida, she finds herself perpetually “stuck.”

So acute is her feeling of economic immobility that she has considered leaving Miami altogether.

“My brother lives in Oregon, and he pays $1,700 for a two-bedroom,” said Germain, reflecting on a potential relocation.

Those at the lower end of the income spectrum feel the pressure of rising rents most intensely, said Annie Lord, executive director of Miami Homes for All. The organization estimates that to relieve cost-burdened households earning less than $75,000 per year, Miami-Dade County will need to build at least 90,000 housing units.

Lord said Miami Homes for All has identified 14,000 units in varying stages of predevelopment in Miami-Dade that are still in need of funding — roughly $1.5 billion total — in order to get built.

While some fear Miami has little space to build, Lord remains optimistic. Across the county, she sees underutilized facilities — buildings owned by hospital systems and the school district, as well as empty commercial units — that could theoretically be converted to affordable housing.

“We can handle this,” she said, “we just need to get over the hump of committing to funding it.”

©2024 Miami Herald. Visit at miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments