Judge orders UAW officials to produce records sought in Shawn Fain corruption probe

Published in Business News

A federal judge Monday ordered United Auto Workers officials to stop withholding documents sought by a watchdog investigating claims of wrongdoing by President Shawn Fain and other senior leaders.

U.S. District Judge David Lawson issued the order three weeks after hearing arguments amid a dispute that has delayed by months attempts by the watchdog, court-appointed monitor Neil Barofsky, to investigate new allegations of wrongdoing after a prolonged corruption scandal that ravaged one of the nation's largest and most influential labor unions.

The order marks one of the most significant decisions since a landmark deal was reached in 2020 between federal prosecutors and the UAW that averted a full-scale takeover of the UAW by the Justice Department.

Barofsky is empowered to oversee UAW operations, investigate and file disciplinary charges designed to eliminate corruption, wrongdoing and unethical practices. But he complained to the judge that union leaders are obstructing and interfering with attempts to access information while his team investigates alleged wrongdoing by Fain and other senior leaders

The "UAW must produce without further delay unredacted copies of all documents demanded by the monitor that are responsive to the demands for production, except for minutes and recordings of meetings that involve discussion of collective bargaining strategy or attorney-client privileged conversations," the judge wrote.

The UAW has provided almost 185,000 documents, or 2 million pages, and redacted less than 600 documents, union attorney Harold Gurewitz told the judge last month. The only documents that had been withheld are text messages from Fain's phone that have been requested from the service provider.

Gurewitz declined comment about the judge's order Monday shortly after it was filed.

The dispute marked the first significant tension surrounding a deal that subjected the union to prolonged government oversight designed to root out corruption. The deal, designed to last six years, installed Barofsky, an attorney, to monitor the UAW's operations and act as a court-approved watchdog, a first-in-UAW-history measure necessitated by a prolonged period of criminality that led to two dozen convictions and sent two UAW presidents — Gary Jones and Dennis Williams — to prison.

The order was filed in federal court in Detroit six months after Barofsky sought clarification on whether the union was obligated to provide direct and immediate access to documents requested by the watchdog's team. This summer, Barofsky revealed he was investigating, among other things, allegations that Fain and his team demanded a subordinate take action to benefit the president's fiancée and her sister.

Barofsky's investigation into Fain does not appear to involve criminal allegations. However, Barofsky can try to discipline, remove, suspend, expel and fine UAW officers and members.

An earlier court filing revealed one of the allegations of retaliation against Fain is that he removed Vice President Rich Boyer as head of the Stellantis Department in May because of “refusal to accede to demands by (Fain) and his agents that (Boyer) take actions … that would have benefitted (Fain's) domestic partner and her sister," the monitor's lawyer, Michael Ross, wrote in a motion filed in federal court in Detroit.

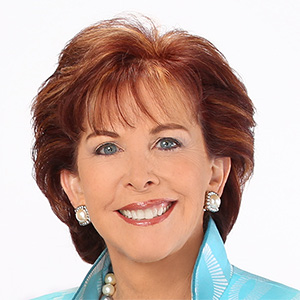

Fain is engaged to Keesha McConaghie, according to his biography on the UAW's website. She is a financial analyst at the World Class Manufacturing Academy at the UAW-Chrysler National Training Center, which was previously overseen by Fain.

Fain has said Boyer's removal was because of a “dereliction of duty” in connection with certain collective bargaining issues. Boyer has defended his representation of members and accused Fain of a "direct attack on my character."

Previous UAW leaders were convicted of a pattern of corruption that included breaking federal labor laws, stealing union funds and receiving bribes, kickbacks and illegal benefits from contractors and auto executives.

In June, Barofsky accused current union officials of interfering with his investigations by delaying the handover of documents sought in connection with the probes. Tensions between the parties increased weeks later when the Detroit-based union filed its own motion requesting that the court clarify whether the union can withhold privileged information covering such areas as collective bargaining and organizing.

Ross wrote that the consent decree was at a “critical juncture.”

“The UAW’s refusal to promptly produce documents requested by the Monitor for use in investigating three current members of the Union’s highest governing body, the International Executive Board … based on assertions of privilege and confidentiality — risks undermining the purpose of the monitor’s appointment and the objectives of the decree,” Ross wrote.

“… The Union has effectively stalled the Monitor’s work,” he added. “These investigations would likely have been resolved by now had the union cooperated with the monitor’s requests.”

The consent decree states the monitor "may require any component of the UAW, or its constituent entities, or any officer, agent, representative, member or employee of the UAW or any of its constituent entities to produce any book, paper, document, record or other tangible object for use in any hearing initiated by the Monitor." It also grants the monitor the right to issue subpoenas requiring "the production of documentary or other evidence pursuant to authority conferred by the Court under this consent decree" and subject to specified federal rules.

The consent decree also gives the monitor permission to attend meetings of the UAW's governing International Executive Board, but states, "The Monitor shall not be entitled to attend or listen to meetings or portions of meetings protected by the attorney-client privilege or concerning collective bargaining strategy."

In the order Monday, the judge also ordered the monitor not to disclose or share documents that could be privileged without giving "reasonable time for the UAW to object."

In February, the monitor sought a range of documents and communications involving high-ranking UAW officials, including Fain. That included emails, text messages and chats sent via the encrypted instant messaging service WhatsApp. As of July, it covered communications from more than 21 elected union officials, staff and outside attorneys and 50 terms like "picket sign" and "exception."

Tensions grew between the union and the monitor over more than just search terms. The requested information came after outside counsel hired by UAW characterized as "inappropriate" actions by Barofsky in raising concerns over UAW statements surrounding the Israel-Hamas war. A statement from a spokesperson for the law firm where Barofsky works said he "has carried out his duties with the highest levels of professionalism and integrity."

In February, Barofsky opened an investigation after the IEB removed Secretary-Treasurer Margaret Mock from overseeing nine departments, including the union's Women’s Department and the Technical Office and Professional Department, over an alleged misuse of her treasury powers. Mock defended her actions in a statement at the time, stating she was adhering to the policies of her role.

Barofsky also is investigating allegations that Mock improperly denied reimbursement requests as well as allegations of retaliation against Fain for the removals of Mock as well as Boyer from their department leadership roles.

©2024 www.detroitnews.com. Visit at detroitnews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments