Commentary: For voters, what Harris or Trump say may matter less than how they say it

Published in Political News

Imagine someone needs to convince you of a surprising fact — say, that your partner is cheating on you. Your best friend might be direct: “They’re cheating on you!” They might even exaggerate a little to get you extra worked up: “It’s been going on for ages! They’re parading around all over town!” But a stranger would need to be more circumspect and subtle: “I’m surprised to hear you’re a couple, because I saw …”

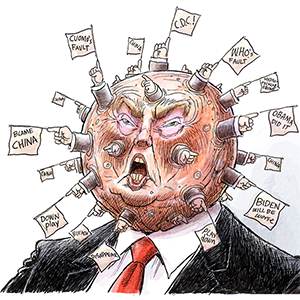

There are essentially two different ways to communicate persuasively, and the differences have everything to do with the communicator’s social authority. We’re seeing it play out on the campaign trail: Donald Trump is regularly characterized as forward and bombastic, while Kamala Harris is often criticized for being too indirect or obtuse. Both styles can be effective, but it’s helpful to consider who uses these different approaches and why.

People we see as trustworthy — either because they are familiar to us or because they are members of a race, class or gender our society treats as authoritative — can use direct and unambiguous language to push others into their way of thinking. If you trust someone, they can convince you of something by speaking straightforwardly about it — and they can be even more effective by taking advantage of their authority and exaggerating the truth. This manner of speech has been historically linked to dictators and fascists, but it’s also something you might see in your day-to-day life from someone in a position of power over you — like your boss — or someone you’re in a close relationship with, like your significant other.

On the other hand, those who are not in positions of authority must be much more subtle and measured. If you are not already inclined to take someone’s word for something, that person doesn’t have the luxury of simply stating the facts as they see them. They have to be more circumspect and make their points implicitly.

One way to be implicitly persuasive is to presuppose something rather than state it outright. One of the differences between the English articles “a” and “the” is that “the” often presupposes uniqueness, i.e., that there is only one. So a politician could bill herself as “an honest politician,” or include a presupposition by claiming she is “the honest politician.” This second option packs a bigger semantic punch but is notably less direct than explicitly saying something like “I am an honest politician, and my rival is not.”

Striving for plausible deniability is another way to be implicitly persuasive. If the point you need to communicate is controversial and potentially socially dangerous and you aren’t in a position of power, it’s a good idea to speak as noncommittally as possible. This is achievable using distancing language or hedging, for example: “If pressed, I might feel that it’s appropriate to suppose your partner might be cheating on you.”

Another way to gain plausible deniability is by using oblique language, such as so-called dog whistles, which signal meaning to one group without alerting others. These techniques rely on a distinction between lying outright and being misleading. Misleading styles are used extensively in persuasion, both by people who can’t afford to be direct and by those with ulterior motives, such as advertisers and public relations experts.

On a day-to-day basis, it’s better to think of indirect language as a natural reflex based on our fluid roles in society, not a sign of weakness to be stamped out. If we had a better understanding of these linguistic power dynamics, we might have, for instance, different legal precedents. One unfortunate court ruling held that saying, “I think I would like to talk to a lawyer” to a police officer does not legally qualify as a request for a lawyer. But stating, “I think I would like a salad” would uncontroversially be seen by a restaurant server as an order — in a context in which the power imbalance is flipped.

Understanding the real motivations for indirect communication also would help us work to avoid gender and racial bias: While Harris is almost always characterized as more indirect than Trump, conversation analysis has shown that Trump used more hedging and uncertain language in their presidential debate. This is consistent with findings that women are disproportionately criticized for using indirect language, when it is more or less equally used by all genders. This is true for tag questions (statements ending with an interrogative question, such as “You watched the debate, didn’t you?”) and vocal fry (a creakiness or raspiness in one’s voice that some assume is an affectation.) Both have been disproportionately associated with women and incorrectly characterized as signaling weakness in the speaker.

It’s important to remember that generally we do not have the luxury of choosing between these two approaches to persuasive communication. The fact that those with power can afford to speak directly, while those without it cannot, means that more than anything, our communication styles reflect the inequities already established in our society.

____

Jessica Rett is a professor of linguistics at UCLA. Her research investigates the meaning of words and how they contribute to the meanings of sentences, either in isolation or in broader contexts.

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments