Philadelphia’s 200-year-old disability records show welfare reform movement’s early shift toward rationing care and punishing poor people

Published in Political News

In 1902, the facility was renamed Philadelphia General Hospital. It was closed in 1977 and soon thereafter leveled. Today, the space houses a range of facilities owned by the PGH Development Corp.

As the Guardians of the Poor manuscript collections held at the Philadelphia City Archives make clear, Blockley Almshouse hired medical professionals to screen those who were admitted and supposedly weed out welfare scammers from those deserving of care.

Sick and injured individuals were sent to the hospital wards, where they encountered physicians and medical students. Students at the University of Pennsylvania completed their clinical rounds at the almshouse, where they performed surgeries, concocted medications and learned how to diagnose patients.

Both disabled and able-bodied poor were sent to the workhouse, where they would perform tasks such as picking oakum – in which you unravel rope into individual fibers – spooling thread, sewing clothes or making shoes. Whatever they produced was sold to local markets to fund the institution.

Reformers presumed that most people would find conditions so abhorrent at the almshouse that they would leave and find work in the city instead.

It’s hard to imagine what the almshouse could provide for families like the Kingleys or the Sions. These families are just two out of 656 listed in the Register of Relief Recipients maintained by the Guardians of the Poor for the year 1829.

Transcribing the record book, I found that all 656 households on the pension lists were home to single parents raising children, elderly persons, persons with disabilities, or some combination of the above. Most had lived in the city for decades.

Ironically, Blockley never turned a profit. Philadelphians continued to fund the institution through poor taxes, and the facility never broke even.

The real costs, of course, were borne by those forcibly institutionalized, separated into wards by gender and health condition, and detached from family members by the expanse of the river.

Many lived in abject poverty to escape the facility. In 1830, Mathew Carey, an economist and public figure in Philadelphia, complained that hundreds of Philadelphians who “have been gradually reduced to the most severe distress and penury – whom honourable men would shudder at seeing inmates of an alms-house, and who, in fact, would rather die than go there” deserved pension support.

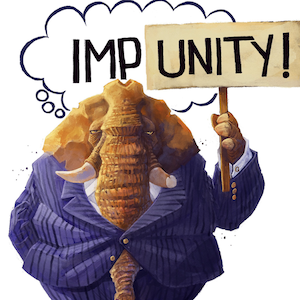

The shift in welfare laws – to defund pensions and fund institutions instead – acted like a net to catch and punish people who were economically dependent. Welfare reformers could have turned an eye on employers, businesses, rental costs or other systemic drivers of poverty. Instead, they focused on supposed scammers who didn’t really exist.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Nicole Lee Schroeder, Kean University

Read more:

Living with a disability is very expensive – even with government assistance

People of color have been missing in the disability rights movement – looking through history may help explain why

US prisons hold more than 550,000 people with intellectual disabilities – they face exploitation, harsh treatment

Nicole Lee Schroeder is thankful to the American Philosophical Society, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Dolores Liebmann Fellowship Fund for supporting this research.

Comments