Philadelphia’s 200-year-old disability records show welfare reform movement’s early shift toward rationing care and punishing poor people

Published in Political News

Charles Kingley was a widower and a single father of four who lived in the Northern Liberties neighborhood of Philadelphia in 1829. He worked at a brewhouse but struggled to secure care for his youngest child, William, who was about 5 years old and nearly blind.

Barbra Sion, a 74-year-old woman living in Southwark, was recorded by welfare officials as “old, sickly, cared for by an adopted child.”

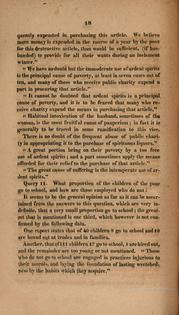

In order to remain in their homes and care for their loved ones, both Philadelphians sought financial support through the Guardians of the Poor, the elected government officials who managed local welfare programs. But in the 1810s and 1820s, these pensions came under suspicion in Philadelphia. Were families like the Kingleys or the Sions really deserving of support, or were they faking it?

As a scholar of early American history, a historian of disability and a disabled individual, I am acutely attuned to arguments about disability spanning the founding of the U.S. to the present day. While researching the daily experiences of disabled Philadelphians in the early 1800s, I discovered the records of the Guardians of the Poor at the Philadelphia City Archives.

In my research, published in the spring 2024 issue of the Journal of the Early Republic, I explore how and why the Guardians of the Poor, alongside other welfare reformers, began rationing care and outlawing pensions.

In the early 1800s, Philadelphia, like most early American cities, had a diversified welfare state.

The Guardians of the Poor levied poor taxes on every home. They used this money to purchase everyday goods such as firewood, food and clothing for the poor, and also to distribute weekly pensions to families in need.

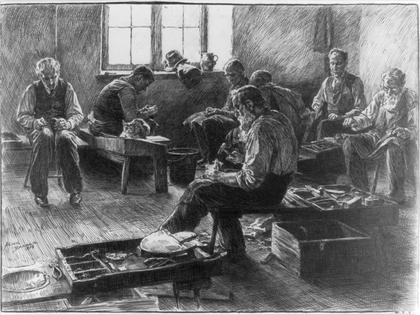

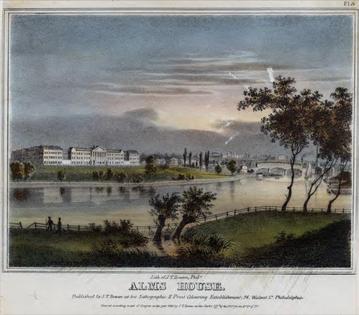

They also supported public institutions like the Philadelphia Almshouse, which provided shelter and met the basic needs for the city’s poorest people. And they purchased spots in the Pennsylvania Hospital, where they referred poor people for medical care.

While the almshouse and hospital were important sites of healing, many disabled households relied on the pension system. Pensioners could get health care in their homes, delivered by physicians hired by the Guardians of the Poor. When provided supplemental income, they could continue working and living independently.

Like most Eastern Seaboard cities in the early 1800s, Philadelphia was home to thousands of immigrants and a growing free Black community. It was also experiencing rising unemployment and vagrancy rates, debts from the War of 1812 against Great Britain, and inflation from the Panic of 1819.

...continued

Comments