Rangers led the way in the D-Day landings 80 years ago

Published in Political News

Among the 150,000 soldiers who landed on and fought across the hostile beaches of Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944, were 1,000 members of a new, specially trained unit – the U.S. Army Rangers.

Most of them fought across the German beachfront defenses, supported by nearly 7,000 naval vessels and 11,000 Allied aircraft. More than 200 Rangers fought vertically – up the sheer cliff face of Pointe du Hoc, a craggy outcropping overlooking the two American landing beaches – in an effort to capture what was thought to be a key location of German artillery.

As a military historian of what I call the American Ranger tradition, I’ve traced this martial phenomenon from the colonial period to the 21st century. Their pathway to Normandy and their exploits that fateful morning represent a core component of the modern U.S. Army’s culture and evolution in the decades since.

The idea for the U.S. Army Rangers was inspired by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s idea for what he called a “butcher and bolt” force – small teams that would conduct surprise attacks, kill or destroy key enemy targets, and escape undetected. The Commandos, as these British units were called, conducted high-profile and daring raids into occupied Europe from 1940 to the end of the war. Their sudden and shocking assaults along the French and Norwegian coastlines provided a boost in British morale during the dark early days of the war.

In spring 1942, Gen. George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army’s chief of staff, agreed to send a small detachment of Americans to train with the British commandos to gain combat experience. These American troops were then supposed to be sent to units across the United States’ rapidly growing army to share their expertise as new recruits prepared to go to war.

Gen. Lucian Truscott Jr., who had made the initial pitch to Marshall, believed the term “commando” was too British and instead argued that these men should be called “Rangers.” Truscott recalled the tenacity, flexibility and aggressive nature of colonial forces like Rogers’ Rangers, famous for daring raids during the French and Indian War in the 1750s and 1760s. Truscott believed that “few words have a more glamorous connotation in American military history” than the word “ranger.”

The 1st Ranger Battalion was trained by the British Commandos. A select few of them joined the British and Canadians in an August 1942 raid across the English Channel into Dieppe, France, which resulted in catastrophic losses and hard-learned lessons for the eventual landings at Normandy. Those Rangers were the first U.S. troops to fight in Europe during World War II.

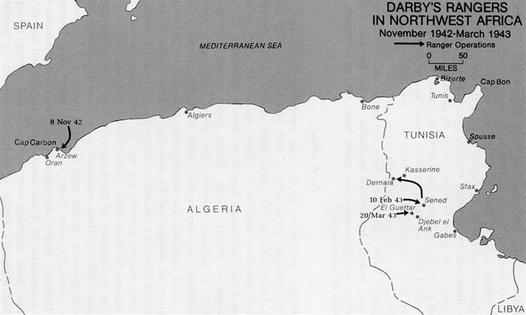

In November 1942, the 1st Ranger Battalion took part in Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of northern Africa. They captured the port town of Arzew, Algeria, without firing a shot during the invasion’s opening hours. They conducted daring nighttime raids, like the one on the Italian military outpost at the Sened Station in Tunisia, and were essential to Gen. George Patton’s breakout at Tunisia’s Djebel el Ank in 1943.

The unit was so successful that the Army created additional Ranger battalions for the invasions of Italy and France, which were still being planned and would be undertaken in 1943 and 1944, respectively.

As these new battalions were forming and training, two in Africa and two in Tennessee, there was some confusion among Army commanders about how they would be used in combat. Were they specialized raiding forces like the commandos, or elite infantry meant to spearhead beach landings and other large-scale offensives? The 1st Rangers had done both in Africa, and these new Rangers would be asked to do so as well.

These new Ranger battalions were less heavily armed than their conventional counterparts. While they fit under the same organizational framework, they lacked the heavier weapons and internal artillery capabilities of a standard American infantry battalion.

As the Allied campaign pushed across northern Africa and into Italy, the Rangers found themselves consistently on the front lines of the Allied advance, where they suffered disastrous casualties fighting in prolonged conventional battles they were neither designed nor equipped for.

Like the rest of the D-Day force, the Rangers prepared for the operation without knowing when or where it would take place.

The newly organized 2nd and 5th Ranger battalions arrived in England in January 1944 and, alongside the more than 2 million other Allied soldiers on the British Isles, started preparing for the Normandy landings. The Rangers completed the murderous Commando training course in Scotland, famous for its grueling hill runs and use of live ammunition, spent weeks practicing amphibious landings along the English coastline, and scaled the towering seaside cliffs near Swanage more times than they could count.

On the fateful morning of the Normandy landings, the Ranger battalions were split into three groups with two distinct assignments.

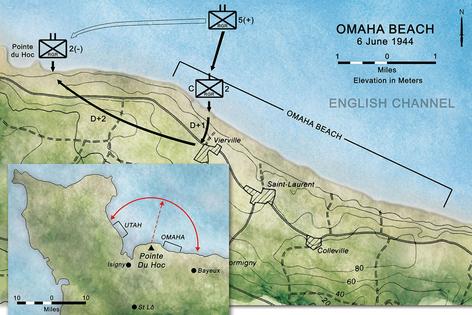

Task Force A, three companies led by Lt. Col. James Rudder, was assigned the most difficult mission: Pointe du Hoc. Using rocket-propelled grappling guns, rope and specialty fire ladders, the Rangers needed to climb 90 feet of sheer rock face under German fire, take the cliff top and destroy a group of 155 mm German guns overlooking the landing beaches.

Task Forces B and C, the remaining Rangers, were insurance. Depending on what happened at the cliffs, these Rangers had to land and fight across Omaha Beach and either rescue a faltering cliff assault or support the 29th Infantry Division in clearing the beach and taking the critical town of Vierville.

Rudder’s Task Force A had a rough start: A wrong turn in their landing craft put them 30 minutes behind schedule. The 225 Rangers finally started their climb well after sunrise and were met with intense German fire from above. Many of the first men to reach the top only did so with their hands and knives – their ropes had been cut.

But 30 minutes after they started climbing, the Rangers had reached the craggy and blasted top of Pointe du Hoc. Numbering barely 70, they found no functional German guns, which had either been destroyed in pre-invasion bombardments or moved by the Germans just days before.

By the time the 800-plus Rangers of Task Forces B and C landed on Omaha Beach, they had not yet heard from the delayed cliff assault team amid the chaos of the morning’s fight.

Within minutes, concentrated German machine gun fire devastated the men struggling up the beach. Nearly half of Lt. Col. Max Schneider’s force were killed or wounded as they made their way onto the beach. The rest hid behind a low seawall. Brig. Gen. Norman Cota approached the gathered troops. After a short and heated discussion with Schneider, the Rangers heard Cota yell something about needing to get troops off the exposed beach.

His order became the current 75th Ranger Regiment’s motto: “Rangers, Lead the Way!” Using explosives specially designed for clearing obstacles, the Rangers cleared a pathway through the German barbed wire, and the assault up the beach began anew.

Famously reenacted by Tom Hanks and his fellow on-screen Rangers in 1998’s World War II epic “Saving Private Ryan,” the Ranger attack kick-started one of the first major breakthroughs of the morning. Before long, American soldiers were face to face with German defenders and opening large gaps in the defenses on their way to taking the beach and pushing inland.

Like most of the troops on D-Day, the men of the 2nd and 5th Rangers experienced combat for the first time on those beaches and cliffsides. They paid a heavy price for the Allied victory: Nearly 400 of the original 1,000 Rangers who set out for Normandy were killed, wounded or missing. Overall, 4,000-plus Allied soldiers were killed on the day of the invasion, with 5,000 more wounded.

The Rangers were a small part of the overall operation, but they epitomize the strength, adaptability and determination of every service member who stepped foot on those beaches, piloted those landing craft, flew air support or toiled on an off-shore warship.

Four decades after D-Day, U.S. President Ronald Reagan visited Pointe du Hoc and paid his respects to the 62 surviving members of the 2nd Rangers who had climbed the cliffs. He honored them – and every other young man who stormed the beaches of Normandy:

“These are the boys of Pointe du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent. These are the heroes who helped end a war.”

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: James Sandy, University of Texas at Arlington

Read more:

A jacket, a coin, a letter − relics of Omaha Beach battle tell the story of D-Day 80 years later

Soviet media downplayed the significance of the D-Day invasion

D-Day succeeded thanks to an ingenious design called the Mulberry Harbours

James Sandy receives funding from the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center at Carlisle Barracks, PA.

Comments