Chinese spy balloon over the US: An aerospace expert explains how the balloons work and what they can see

Published in Political News

Officials of the U.S. Department of Defense confirmed on Feb. 2, 2023, that the military was tracking what it called a “spy balloon” that was drifting over the continental United States at an altitude of about 60,000 feet. The following day, Chinese officials acknowledged that the balloon was theirs but denied it was intended for spying or meant to enter U.S. airspace. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that the balloon’s incursion led him to cancel his trip to Beijing. He had been scheduled to meet with Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang on Feb. 5 and 6. On February 3, the Pentagon said that a second suspected Chinese balloon was seen over Latin America.

Monitoring an adversary from a balloon dates back to 1794, when the French used a hot air balloon to track Austrian and Dutch troops in the Battle of Fleurus. We asked aerospace engineer Iain Boyd of the University of Colorado Boulder to explain how spy balloons work and why anyone would use one in the 21st century.

A spy balloon is literally a gas-filled balloon that is flying quite high in the sky, more or less where we fly commercial airplanes. It has some sophisticated cameras and imaging technology on it, and it’s pointing all of those instruments down at the ground. It’s collecting information through photography and other imaging of whatever is going on down on the ground below it.

Satellites are the preferred method of spying from overhead. Spy satellites are above us today, typically at one of two different types of orbit.

The first is called low Earth orbit, and, as the name suggests, those satellites are relatively close to the ground. But they’re still several hundred miles above us. For imaging and taking photographs, the closer you are to something, the more clearly you can see it, and this applies to spying as well. The satellites that are in low Earth orbit have the advantage that they’re closer to the Earth so they’re able to see things more clearly than satellites that are farther away.

The disadvantage these low Earth orbit satellites have is that they are continually moving around the Earth. It takes them about 90 minutes to do one orbit around the Earth. That turns out to be pretty fast in terms of taking clear photographs of what’s going on below.

The second type of satellite orbit is called geosynchronous orbit, and that’s much farther away. It has the disadvantage that it’s harder to see things clearly when you’re very, very far away. But they have the advantage of what we call persistence, allowing satellites to capture images continuously. In those orbits, you’re essentially overlooking the exact same piece of ground on the Earth’s surface all the time because the satellite moves in exactly the same way the earth rotates – it rotates at the exact same speed.

A balloon in some ways gets the best of those. These balloons are much, much closer to the ground than any of the satellites, so they can see even more clearly. And then, of course, balloons are moving, but they’re moving relatively slowly, so they also have a degree of persistence. However, spying is not usually done these days with balloons because they are a relatively easy target and are not completely controllable.

I don’t know what’s on this particular spy balloon, but it’s likely to be different kinds of cameras collecting different types of information.

These days, imaging is conducted across different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Humans see in a certain range of this spectrum, the visible spectrum. And so if you have a camera and you take a photograph of your dog, that’s a visible photograph. That’s one of the things spy aircraft do. They take regular photographs, although they have very good zoom capabilities to be able to magnify what they’re seeing quite a lot.

But you can also gather different kinds of information in other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Another fairly well-known one is infrared. If it’s nighttime, a camera operating in the visible part of the spectrum is not going to show you anything. It’s all going to be dark. But an infrared camera can pick up things from heat in the dark.

Most of these balloons literally go where the wind blows. There can be a little bit of navigation, but there are certainly not people aboard them. They are at the mercy of whatever the weather is. They sometimes have guiding apparatus on them that change a balloon’s altitude to catch winds going in particular directions. But it’s pretty much wherever the wind’s blowing, that’s where you’re going.

There are machine learning-types of approaches that would seek to optimize your path, so that if you’re trying to get from A to B, you can get closer. But if the prevailing winds are just going completely in the opposite direction to where you want to go, there’s really no way to get there with a balloon.

There is an internationally accepted boundary called the Kármán Line at 62 miles (100 kilometers) altitude. This balloon is well below that, so it is absolutely, definitely in U.S. airspace.

The Pentagon has had programs over the last few decades studying balloons, different aspects of what can be done with balloons that couldn’t be in the past. Maybe they’re bigger, maybe they can go higher in the atmosphere so they’re more difficult to shoot down or disable. Maybe they could be more persistent. But I’m not aware of any countries actively using spy balloons these days. There have been unconfirmed reports of potential spy balloons in Asia that have been attributed to China.

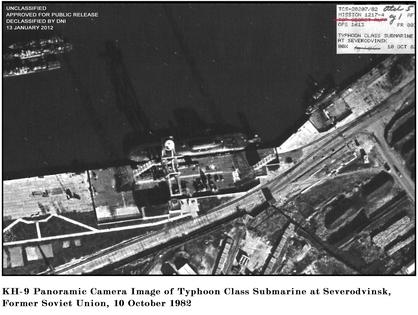

The U.S. flew many balloons over the Soviet Union in the 1940s and 1950s, and those were eventually replaced by the high-altitude spy airplanes, the U-2s, and they were subsequently replaced by satellites.

I’m sure a number of countries around the world have periodically gone back to reevaluate: Are there other things we could do now with balloons that we couldn’t do before? Do they close some gaps we have from satellites and airplanes?

China has complained for many years about the U.S. spying on China through satellites, through ships. And China is also well known for engaging in somewhat provocative behavior, like in the South China Sea, sailing close to other nations’ boundaries and saber-rattling. I think it falls into that category.

The balloon doesn’t pose any real threat to the U.S. I think sometimes China is just experimenting to see how far they can push things. This isn’t really very advanced technology. It’s not serving any real military purpose. I think it’s much more likely some kind of political message.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. Like this article? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more:

War in Ukraine highlights the growing strategic importance of private satellite companies – especially in times of conflict

How many satellites are orbiting Earth?

Iain Boyd receives funding from the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of Energy, NASA, and Lockheed-Martin.

Comments