Andreas Kluth: Trump's trash talk revives the worst of world politics

Published in Op Eds

Donald Trump, just days from returning to the Oval Office, wants friend and foe to know that he’s wrestled with an alligator, tussled with a whale, murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalized a brick — because he’s so mean he makes medicine sick.

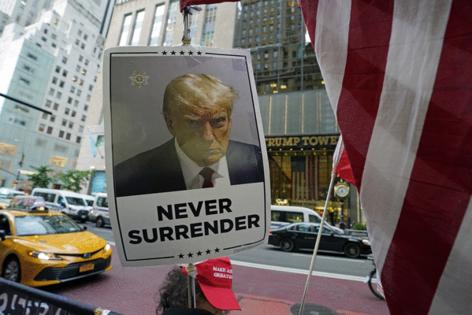

Oh wait, that was Muhammad Ali, in the heyday of his boxing and epic trash-talking before bouts. Trump — especially in the run-up to his inauguration — is clearly challenging The Greatest for his title of GOAT in smack talk, chirping, jawing, or whatever you call it.

That must be why Trump has recently put Panama on notice that the U.S. wants that canal back; Denmark, that he intends to make an offer to buy Greenland that Copenhagen can’t refuse; and Canada, that it should start looking forward to becoming the 51st American state.

Trump (probably) doesn’t mean much of this literally, just as Ali left most rocks, stones, bricks and other masonry unmolested. But that’s not the point of trash talk. With his constant and winky microaggressions, Trump, like Ali, is trying to put psychological pressure on foreign nations and their leaders, the better to destabilize them now and bend them to his will later. That way, he reckons, there may be a chance of a technical KO in the ring, or as Trump calls it, “peace through strength.”

Even so, trash talk is never just talk. It’s as open to exegesis as body language, tea leaves or tarot cards are.

The first curio is that Trump as president-elect is directing his chirping at nations — Panama, Canada, Denmark — that are small, pro-American or even allied. Why not Russia, China, or North Korea? This is like Muhammad Ali preparing for a bout by intimidating a gentle opinion columnist instead of George Foreman. Whatever message Trump thinks he’s sending to Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping or Kim Jong-Un, it’s not exactly one of strength.

A clue may hide in another pattern to this trash talk, for there’s definitely method in the madness. If you discard principles in foreign affairs — as enshrined in international law — and analyze the world purely in terms of power and interests, each of the three taunts makes an eerie sort of sense.

Start with the Panama Canal. The United States built this passage linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and managed it for most of the 20th century before irrevocably giving it to Panama in 1999. Since then, the canal has been neutral and run — very professionally — by an independent authority.

Of late, that agency has struggled with drought (which complicates filling the locks). But it does not, contrary to Trump’s absurd accusation of a “complete ripoff,” discriminate between vessels of different flags. Nor does the canal teem with “the wonderful soldiers of China,” as Trump risibly claims.

If you look more closely, though, there is indeed a company based in Hong Kong, the allegedly “special administrative region” that China clasps with an increasingly dictatorial grip, which runs two of the ports at its entrances on the Pacific and the Atlantic. China is also the canal’s second-highest user, after the U.S. (Perhaps coincidentally, Panama switched its diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing during Trump’s first term.)

A British or French statesman in the 19th century would look at a world map and these circumstances and conclude that his country, and no other, should control this strategic node, decorum be damned. Trump seems to share that instinct.

A similar rationale applies to Greenland. It’s an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, but also rich in rare earths and other treasures. Even more importantly, it’s a gateway to the Arctic, which is becoming more important geopolitically as its ice thaws and allows ships to pass for more of the year.

For that and other reasons, the U.S. already has a base in Greenland for missile defense and space surveillance. And now China is eager to get in too. (For a nail-biter version about Greenland as a plaything between the great powers, watch season four of the Danish series Borgen.) Whether Trump looks at Greenland with the eyes of a real-estate developer or a strategist, it certainly looks tempting to own.

Nudging Canada to become the 51st state, while simultaneously threatening it with trade war, is of course the height of cheekiness. Then again, it’s hardly a punch line that Canadians haven’t heard (or told) before. In geopolitical terms, the two North American countries have long resembled Tweedledee and Tweedledum: As Ronald Reagan used to say when crossing the northern border, “we’re more than friends and neighbors and allies; we are kin.” Trump probably feels the same way; he just wants more money and lacks Reagan’s manners.

The rejoinder is obvious. As Panamanian President Jose Raul Mulino puts it, in a way that his Canadian and Danish counterparts would endorse: “The sovereignty and independence of our country are not negotiable.” So say the letter and spirit of international law, including a treaty (ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1978) in the Panamanian case, and more generally the charter of the United Nations, as drafted and signed after World War II under the benevolent gaze of the U.S.

All American presidents since then except for Trump have accepted its principles as self-evidently good and conducive to America’s own national interest. The resulting system is what Washington has long called the “liberal” or “rules-based” international order. Imperfect as it has been, it strives to balance might against right, interests against values, and realism with idealism.

Trump, with his trash talk, is once again hinting that he disdains this larger, albeit more abstract, definition of America’s interests, and that he instead means to emulate rather than oppose the likes of Putin and Xi as they speak the language of raw power and spheres of influence.

So he picks on three countries in the western hemisphere, deemed to lie within Washington’s domain since James Monroe proclaimed his doctrine two centuries ago. If there is a signal to Moscow and Beijing, it may be that Trump will indulge hallucinations about “the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” or equivalent theories about the Taiwan Strait, as long as he can talk bigly and carry any kind of stick closer to home.

There is nothing new about this worldview; it’s simply a reversion to the historical norm in international affairs, which scholars call anarchy, and which can at times resemble a boxing ring. Today as ever, this default state may suit the great powers. But smaller nations everywhere should re-read the chapter in Thucydides on the rape of Melos and shudder. Trump won’t invade Panama, Greenland or Canada. But he wouldn’t defend Ukraine either; nor, possibly, Taiwan or even Japan or Estonia.

I love a good trash-talking as much as anybody, but on literal arenas, not on the world stage. Once an American president gets in this game, the risk is too high that he really does make medicine sick.

____

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering U.S. diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments