The world’s fourth mass coral bleaching is underway, but well-connected reefs may have a better chance to recover

Published in Science & Technology News

The world’s coral reefs are like underwater cities, bustling with all kinds of fish and sea animals. Coral reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean, but they support an estimated 25% of all marine species, including many important fish species. The economic value of the services that these complex ecosystems provide is estimated at over US$3.4 billion yearly just in the U.S.

Today, rising ocean temperatures threaten many reefs’ survival. When ocean waters become too warm for too long, corals expel the colorful symbiotic algae, called zooxanthellae, that live in their tissues – a process called coral bleaching. These algae provide the corals with food, so bleached corals are vulnerable to starvation and disease and may die if the water does not cool quickly enough.

With global ocean heat at record levels, scientists have confirmed that a global coral bleaching event is underway. Since the beginning of 2023, corals have been dying in the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic oceans, both north and south of the equator.

The current bleaching event in the wider Caribbean region is longer and more severe than any previous bleaching episode recorded since the first global one in 1998. I study large-scale climate and ocean dynamics and am analyzing how biological connections between coral reefs – sometimes extending over great distances – may help reefs recover from heat stress.

Given how quickly ocean temperatures are warming, scientists are working to develop response strategies. These include making corals more heat-tolerant; restoring damaged areas with healthy corals; relocating coral nurseries to cooler areas; breeding “super corals” that are more resistant to these stresses; and enhancing natural chemical signals and sound cues to attract larval corals and fish to damaged reefs.

Many species of fish found on coral reefs play valuable roles in keeping these communities healthy. For example, seaweeds compete with corals for space and light, and often will take over reefs after bleaching episodes.

Corals remain healthier and recover faster if they are surrounded by fish that eat different types of seaweed, such as parrotfish, surgeonfish and rabbitfish. Reflecting their role, these species often are referred to collectively as grazers.

Sea cucumbers – leathery bottom-dwellers, distantly related to starfish and urchins – also are important reef partners. They feed on bacteria and other organic materials in ocean sediments, cleaning up the area around reefs.

My Georgia Tech colleague Mark Hay recently published a study which showed that removing sea cucumbers from reef communities led to an increase in organic waste materials and a 15-fold rise in coral deaths. Protecting sea cucumbers, which are overharvested as a food source, could help keep coral reefs healthy.

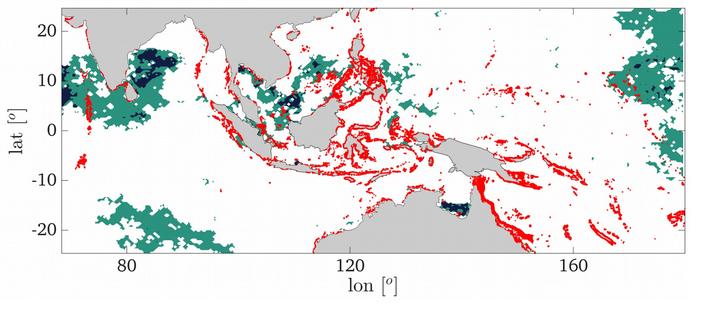

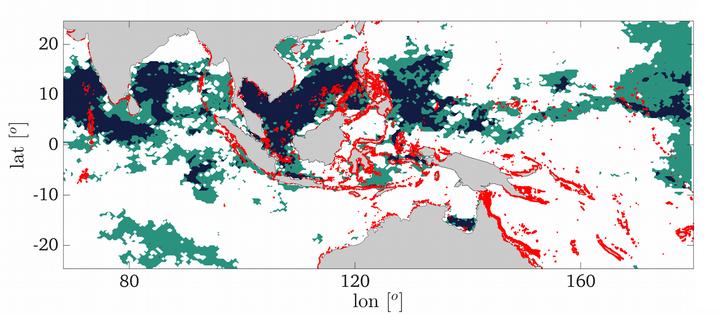

Coral reefs are not isolated outposts. When fish and corals spawn, they release millions of larvae that drift on currents and are exchanged across reefs through mixing and transport processes. These exchanges make up the connectivity of coral reefs.

...continued

Comments