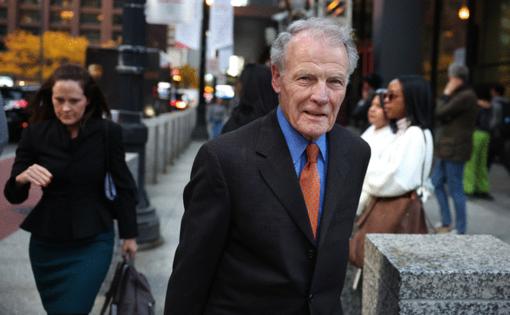

'We have to play hardball': Testimony in Madigan corruption trial turns to 2018 sex harassment scandal

Published in News & Features

CHICAGO — In June 2018, the day House Speaker Michael Madigan’s longtime chief of staff had quit amid a burgeoning sexual harassment scandal, two of Madigan’s top deputies had a frank conversation about trying to save their boss.

“It’s time to get a real PR firm in here…somebody who’s dealt with real (expletive) … like the Clinton impeachment,” Will Cousineau, a lobbyist who had served as Madigan’s political director, told Michael McClain, the speaker’s loyal confidant. “It’s gonna cost us a ton of (expletive) money, but if this saves him, so be it.”

McClain agreed, and told Cousineau he had “three or four different companies” in mind.

“You want me to give you the names or do you want me to call?” McClain said. “I just think we gotta get somebody in here that’s playing hard ball. You’re doing nine other things — this guy would just be focused on saving the speaker.”

“I agree,” Cousineau replied.

The call, which was secretly recorded by the FBI, was played at Madigan’s corruption trial Thursday, where testimony ventured into the #MeToo-era sexual harassment scandal that had engulfed the speaker’s office and posed the most significant threat in decades to his grip on power.

Prosecutors are presenting the sexual harassment scandal as evidence of the lengths that Madigan’s soldiers would go to protect the boss, and to show Madigan had the willingness and power to provide a soft landing for someone close to him who was in trouble. But it also serves as a sort of autopsy of how Madigan’s record reign at the pinnacle of Illinois politics began to fall apart.

In another call played for the jury, Cousineau tells McClain that Madigan had “signed off on a crisis management firm” and that they were looking to bring them to Chicago to discuss the situation.

Cousineau told McClain that the circle of loyalists who would work on it would include him, McClain, former Madigan staffer Mike Thomson, lobbyist Tom Cullen, and 13th Ward Ald. Marty Quinn.

The firm they wound up hiring was headed by Anita Dunn, a longtime political strategist based in Washington.

On the witness stand Thursday, a prosecutor asked Cousineau how big a deal it was for him and the rest of Madigan’s team that the chief of staff, Tim Mapes, had been forced to resign.

“It was a significant event,” Cousineau said haltingly.

Madigan, 82, of Chicago, who served for decades as speaker of the Illinois House and the head of the state Democratic Party, faces racketeering charges alleging he ran his state and political operations like a criminal enterprise, scheming with utility giants ComEd and AT&T to put his cronies on contracts requiring little or no work and using his public position to drum up business for his private law firm.

Both Madigan and McClain, 77, a former ComEd contract lobbyist from downstate Quincy, have pleaded not guilty and denied wrongdoing.

Cousineau is the eighth witness to testify in Madigan’s trial, which began Oct. 8 and is scheduled to last until at least mid-December.

Madigan’s decision to force Mapes to resign as chief of staff, House clerk and executive director of the Madigan-run state Democratic Party over a #MeToo scandal represented the culmination of a year of reckoning in Springfield.

The scandal began in February 2018 when campaign worker Alaina Hampton called out top Madigan lieutenant Kevin Quinn over his relentless string of inappropriate communications, including one text calling her “smoking hot,” despite her saying she wanted him to stop.

The jury has yet to hear such details and may not. Hampton is expected to testify for prosecutors later in the trial, but she will be prevented from speaking about the specifics of her sexual harassment allegations.

Madigan ousted Quinn, the brother of Madigan’s hand-picked 13th Ward Ald. Marty Quinn, but a clamor in Springfield erupted over how Madigan would address mistreatment of women.

Defense attorneys on Thursday morning launched an unsuccessful last-ditch effort to prevent jurors from hearing anything about the Kevin Quinn matter, even though U.S. District Judge John Robert Blakey had already ruled that any specifics about the accusations were off-limits.

Other testimony Thursday centered on an alleged scheme by McClain to secretly arrange monthly payments for Quinn from a cadre of lobbyists loyal to the speaker’s organization, including Cousineau.

The Tribune first broke the story in 2019 that federal investigators were looking at the checks sent to Quinn as part of a criminal investigation, which was later revealed to be the ComEd bribery scheme.

With Cousineau on the stand, prosecutors played an Aug. 28, 2018, recorded call where McClain told Cousineau that Quinn had asked him for a job.

McClain said Madigan “intends to help” Quinn once he was sworn in as speaker and “gets his rules,” but for now, McClain was just trying to arrange some money to get him by, something along the lines of $1,000 a month from a group of five people.

“I’d like to keep the list of people that know this real small,” McClain said on the call. “The more people that know, it’s just too easy for people to babble.”

Cousineau asked, “He would not register, correct?”

McClain: “No, no, no, solely a consultant. As far as I’m concerned except for the people signing on, no one else even knows about it except for our friend.”

Asked on the witness stand who he understood “our friend” to be, Cousineau replied, “The speaker.”

On the call, Cousineau told McClain he wanted to “be a team player” but was worried about whether his company would go for it. He also said that if he did hire Quinn, he could use him for actual work.

Cousineau told the jury he could hear the “hesitancy” in his own voice on the call.

“I was incredibly concerned about it. But again, I wanted to be a team player,” he testified.

A few days after the first call, McClain and Cousineau spoke again about the plan.

“I can give (Quinn) things to do right?” Cousineau asked.

“It’s up to you, McClain responded, saying he’d envisioned Quinn doing a report on a group of legislators and city council members, maybe writing up “little known things … like who their sugar daddies are, things like that.”

Cousineau said instead of “the bull(expletive) report,” he could use Quinn to sit in on hearings when he was double booked and write up what happened.

The jury has heard a stipulation that Madigan was informed of allegations of “misconduct” against Quinn, and that as a result Quinn was terminated. But the misconduct was not specified as sexual harassment to avoid prejudicing the jury.

____

©2024 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments