Black economic boycotts of the civil rights era still offer lessons on how to achieve a just society

Published in News & Features

Signed into law nearly 60 years ago, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in the U.S. based on “race, color, sex, religion, or national origin.”

Yet, as a historian who studies social movements and political change, I think the law’s most important lesson for today’s movements is not its content but rather how it was achieved.

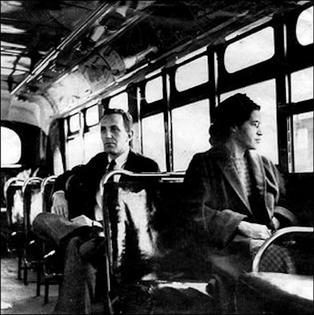

As firsthand accounts from the era make clear, the movement won because it directly hurt the interests of white business owners. The 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, the 1963 boycott of Birmingham businesses and many lesser-known local boycotts inflicted major costs on local business owners and forced them to support integration.

A view common among scholars, activists and the general public holds that the Civil Rights Movement succeeded because violent attacks against peaceful Black protesters mobilized white public opinion in the movement’s favor.

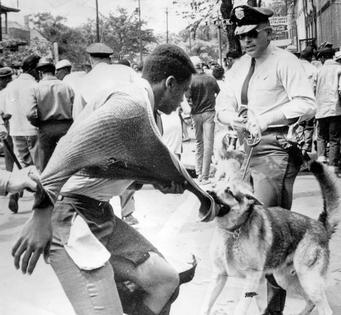

One of the most famous incidents occurred in Birmingham, Alabama, in May 1963, when the city’s public safety commissioner, Eugene “Bull” Connor, turned fire hoses and dogs on Black demonstrators.

The conventional wisdom is that Connor’s actions outraged Northern whites, and in response, the Kennedy administration sent federal troops to Birmingham and a civil rights bill to Congress.

But this view misunderstands the source of the movement’s power.

For one thing, it overstates public sympathy for the Civil Rights Movement. Three months after the attacks against Black protesters in Birmingham, for instance, almost two-thirds of the public opposed the famous March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom of August 1963.

Moreover, the Kennedy administration predicted that civil rights legislation would hurt the Democrats electorally. “The President never had any illusions about the political advantages of equal rights,” wrote Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger in his memoir “A Thousand Days.” “But he saw no alternative” given the movement’s actions.

So what were those actions?

...continued

Comments