Flirting with disaster: When endangered wild animals try to mate with domestic relatives, both wildlife and people lose

Published in News & Features

Fatal attractions are a standard movie plotline, but they also occur in nature, with much more serious consequences. As a conservation biologist, I’ve seen them play out in some of Earth’s most remote locations, from the Gobi Desert to the Himalayan Highlands.

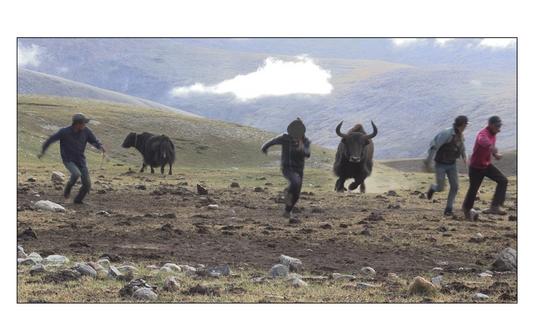

In these locales, pastoralist communities graze camels, yaks and other livestock across wide ranges of land. The problem is that often these animals’ wild relatives live nearby, and huge, testosterone-driven wild males may try to mate with domestic or tamed relatives.

Both animals and people lose in these encounters. Herders who try to protect their domestic stock risk injuries, emotional trauma, economic loss and sometimes death. Wild intruders can be displaced, harassed or killed.

These clashes threaten iconic and endangered species, including Tibetan wild yaks, wild two-humped camels and Asia’s forest elephants. If the wild species are protected, herders may be forbidden from chasing or harming them, even in self-defense.

Human-wildlife conflict is a widely recognized challenge around the world, but clashes in these remote outposts receive less attention than those in developed areas, such as pumas ranging into U.S. exurbs. As I see it, protecting threatened and endangered species won’t be possible without also helping herders whose lives are affected by conservation policies.

The force driving these raids is pure biology. All domestic animals are descended from wild ancestors. Steeped in evolution, natural selection has favored males who inseminate the most females – and females who leave reproductive offspring of their own. Attractions can go both ways: Sometimes smaller or less aggressive domestic males may mate with wild females.

Many herding societies contend with this challenge. In the Hindu Kush mountain system of Central Asia and farther east, Tibetans, Uyghurs, Changpa and Nepalis raise domestic yaks, which provide meat, milk, transportation and shaggy hides for clothing.

Wild yaks were once thought extinct in Nepal, until a team led by wildlife biologist Naresh Kusi rediscovered them in 2014. Now aggressive contests between domestic and wild yaks are headaches for local herders.

In Africa, Namib Desert mountain zebras, a vulnerable species, have been bred by donkeys. In northern China and Mongolia, domestic and reintroduced Przewalski horses coexist in tense zones where herders work to prevent genetic exchanges. In Southeast Asia, wild cattle species, such as gaur and banteng, have mixed extensively with domestic cattle and buffaloes.

In northern realms, caribou and reindeer, which are the same species, Rangifer taranadus, both occur in wild forms. Reindeer have also been domesticated and are central to Indigenous herding cultures in Scandinavia, Russia, Canada and Alaska. Caribou slaughters and separation efforts have not prevented mixing.

...continued

Comments