Business

/ArcaMax

US consumers face possibility of higher beef prices in 2026

American beef lovers may face even leaner plates and higher prices next year as US production shrinks to a decade low and tariffs limit imports, according to a US government projection.

Total beef supply in the US is expected to drop 2.5% in 2026 to 31.1 billion pounds — the lowest since 2019 — the US Department of Agriculture said in a ...Read more

Boeing plane deliveries dipped in July as company recovery rolls on

Boeing delivered 48 planes in July, including 37 of its popular 737 Maxes, the company said in its monthly recap of orders and deliveries Tuesday.

That’s a dip from June — when Boeing reported 60 deliveries, including 42 Max planes — but in line with the company’s output for the earlier months of the year.

Between January and May, ...Read more

Las Vegas funeral home shut down for failing to cremate bodies: 'The smell was straight up death'

A Las Vegas funeral home has been shut down after a regulatory board found that it was failing to cremate bodies for extended periods and failing to file death records in a timely manner.

The Nevada State Board of Funeral & Cemetery Services revoked the license of McDermott’s Funeral Home and Cremation Services last week after alleging that ...Read more

San Diego's inflation rate is highest in nation at 4%

San Diego’s inflation rate was 4% in July — fueled primarily by rising prices for food, medical care and cars — making it highest in the nation.

Inflation has typically run hotter in San Diego than much of the U.S. because of high housing and gasoline costs. Yet the past few reports, which are released every two months for metro areas, ...Read more

Inflation stayed steady last month as Trump's tariffs hit some prices -- here's what might feel most expensive

Inflation didn’t improve last month, suggesting that businesses may be starting to pass along higher costs from tariffs onto the prices that you see on store shelves.

Consumer prices rose 0.2% between June and July, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)’ latest monthly consumer price index (CPI) report. Excluding food and energy...Read more

US core CPI picks up on services; goods inflation more subdued

Underlying U.S. inflation accelerated in July though the cost of tariff-exposed goods didn’t rise as much as feared, boosting expectations that Federal Reserve officials will lower interest rates when they meet next month.

The core consumer price index, which excludes the often volatile food and energy categories, increased 0.3% from June, ...Read more

US core CPI picks up on services; goods inflation more subdued

Underlying U.S. inflation accelerated in July by the most since the start of the year, though a tepid rise in the costs of goods tempered concerns about tariff-driven price pressures.

The core consumer price index, which excludes the often volatile food and energy categories, increased 0.3% from June, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics ...Read more

Spirit Airlines issues warning about its future. Will company stay in business?

Spirit Airlines on Monday warned investors and passengers that it may no longer be in business in a year even after a successful bankruptcy restructuring and recent attempts to generate new sources of revenue.

The alert came in a 222-page financial statement the Broward company is required to submit every quarter to the U.S. Securities and ...Read more

Ossoff urges Trump official to reinstate millions in Black-owned business funding

U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff of Georgia is urging the Trump administration to reinstate millions in federal grant funding to the Urban League of Greater Atlanta for a program aimed at providing support and technical assistance to Atlanta’s Black entrepreneurs.

Ossoff, a Democrat, sent a letter to Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick in early August ...Read more

Why companies born and raised in California are leaving the state

Last month, billionaire In-N-Out owner Lynsi Snyder announced her move from California to Tennessee, where she plans to open new restaurants and continue raising her family.

It’s a dramatic shift for the leader of the beloved West Coast brand, which has become the latest company to signal its dissatisfaction with California in recent years. ...Read more

Rats! More than 100,000 acres of almond orchards across Central California are infested

Almond growers across Central California say they are battling a surging rat infestation across more than 100,000 acres of orchards, resulting in economic hardship and damage.

Across Fresno, Merced, Kings and Kern counties, almond farmers have reported an increase in rodent populations as the rodents use irrigation canals and other waterways ...Read more

3M's PFAS litigation far from over, billions more in settlements likely

Thousands of Americans who blame 3M’s PFAS-laden firefighting foams for giving them cancer will present their claims to a jury for the first time this fall.

Unless they reach a settlement with the Maplewood-based company first.

“The worst-kept secret in this litigation right now is that these lawsuits are expected to settle soon,” ...Read more

Historic downtown Las Vegas casino taking out all live dealer tables

It is the end of an era, as the oldest casino property in downtown Las Vegas is eliminating traditional table games in favor of a new gambling experience.

Golden Gate will no longer offer live dealer table games, according to owner Derek Stevens. The 119-year-old property will phase out live dealer tables over the next several weeks, replacing ...Read more

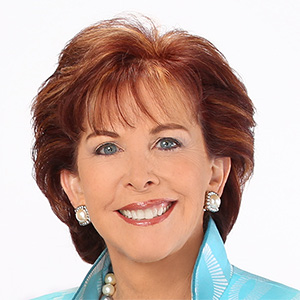

What's next for SAG-AFTRA as Fran Drescher declines to seek reelection

Fran Drescher's decision to not run for reelection as SAG-AFTRA president opens up the race to lead a major Hollywood labor union at a pivotal time as actors face issues such as the rise of AI and a challenging job market two years after a long strike.

Actors Sean Astin and Chuck Slavin are seeking to succeed Drescher in the upcoming election ...Read more

Family sues Stellantis over Toledo Jeep plant death: 'The worst news ever'

The wife of the 53-year-old man who was fatally crushed at Toledo, Ohio's Jeep plant a year ago sued Stellantis NV on Monday, alleging the automaker didn't have adequate safety guards in place that could have prevented his death.

Toledo resident Antonio Gaston, the father of three adult children and a teenager, died Aug. 21 while working in the...Read more

Trump administration pledges to keep, streamline much-maligned EV charger program

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration, months after signaling it might gut the effort completely, unveiled plans on Monday to expedite a Biden-era program focused on building public electric vehicle chargers nationwide.

The U.S. Department of Transportation said it would alter requirements in the $5 billion National Electric Vehicle ...Read more

Nvidia, AMD reach deal to give US a cut of China AI chip sales

Nvidia Corp. and Advanced Micro Devices Inc. have agreed to pay 15% of their revenues from Chinese AI chip sales to the U.S. government in an unusual, legally questionable deal that reflects the Trump administration’s willingness to soften export controls in exchange for financial payouts.

Nvidia plans to share 15% of the revenue from sales ...Read more

Paramount lands UFC rights in $7.7B streaming and TV deal

In a major early move under new ownership, Paramount acquired the media rights to UFC's mixed martial arts events in the U.S., the company said Monday.

Paramount signed a seven-year deal with TKO Group Holdings that will put 13 marquee events and 30 fight nights on streaming platform Paramount+. Some of the matches will air on broadcast TV ...Read more

AOL to pull the plug on dial-up internet after more than 30 years

AOL will pull the plug and end its dial-up internet service after more than 30 years.

The ISP said it will discontinue dial-up — along with its memorable, high-pitched connecting noise and “You’ve got mail” greeting — and “associated software” on Sept. 30.

“AOL routinely evaluates its products and services and has decided to ...Read more

Nvidia, AMD to pay 15% of China AI chip sales to US in deal

Nvidia Corp. and Advanced Micro Devices Inc. agreed to pay 15% of their revenues from Chinese AI chip sales to the U.S. government in a deal to secure export licenses, an unusual if not unprecedented arrangement that stands to unnerve U.S. companies and Beijing alike.

Nvidia plans to share 15% of the revenue from sales of its H20 AI accelerator...Read more

Popular Stories

- Why companies born and raised in California are leaving the state

- Historic downtown Las Vegas casino taking out all live dealer tables

- 3M's PFAS litigation far from over, billions more in settlements likely

- Rats! More than 100,000 acres of almond orchards across Central California are infested

- Spirit Airlines issues warning about its future. Will company stay in business?