Justice Ginsburg's Damage to the Supreme Court

WASHINGTON -- Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's admittedly "ill-advised" remarks about Donald Trump weren't only bad for the justice and her reputation. They were bad for the Supreme Court and, consequently, for the country.

Ginsburg was correct in her scathing assessment of Trump -- and correct to express her "regret" for voicing it publicly. But the damage to the court's image and reputation is already done.

The good news for the justices is that their institution is held in higher regard, for what that's worth, than the other two branches of government.

The bad news is that this support is at an all-time low. According to polling last September by the Pew Research Center, 42 percent of Americans held an unfavorable view of the court, while 50 percent viewed it favorably. By contrast, in January 1988, just 13 percent had an unfavorable view of the court, and 79 percent saw it favorably.

Embedded in this declining assessment is a significant partisan divide: 38 percent of Republicans and Republican leaners viewed the court favorably, compared with 64 percent of Democrats and Democratic leaners. Interestingly, not so long ago, this ideological gap was reversed: in 2008, 80 percent of Republicans viewed the court positively, versus 64 percent of Democrats.

Why does this matter? Why should the justices care? After all, the court is empowered to say what the law is, whether or not the public is happy with its performance and its pronouncements. The justices enjoy life tenure.

Yet stature and public acceptance matter. The court has no independent power, of purse or of sword, to enforce its rulings. The court "cannot buy support for its decision by spending money, and, except to a minor degree, it cannot independently coerce obedience to its decrees," a three-justice plurality noted in the 1992 abortion ruling declining to overrule Roe v. Wade. "The court's power lies, rather, in its legitimacy, a product of substance and perception."

It is naive to imagine that justices don't have political views, or strong political preferences. Of course they do. It is the rare justice who ends up on the court without having ties to politics and politicians.

As the late Justice Antonin Scalia pointed out in arguing that he needn't recuse himself from a case in which Vice President Dick Cheney was a party after the two went on a hunting trip, "from the earliest days down to modern times justices have had close personal relationships with the president and other officers of the executive."

But there is a difference -- a big one -- between having a pre-existing political relationship or predilection that the public might reasonably presume (no one would mistake Ginsburg for a potential Trump voter) and one that is so strongly held that the justice feels impelled to make it public.

That approach is not mere window-dressing. Judicial silence is the tribute that the imperative to appear impartial pays to reality.

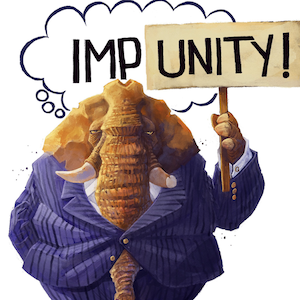

Some people will read this and snort: The justices are political animals like all the others; they decide based on their political views, not on the law.

This dismissiveness ignores and obscures the distinction between ideology and partisanship. Broadly speaking, Republicans and Democrats have differing conceptions of the role of the judiciary, the meaning of the Constitution, and the proper approach to its interpretation; it is no surprise, and no tragedy, that judges appointed by Republican presidents tend toward one set of reasonably predictable conclusions and those named by Democratic presidents another.

But there are, or should be, limits to this linkage. Ruling on the reflexive basis of partisanship is different from a decision guided by ideology. That is one reason the court's 2000 decision in Bush v. Gore was so disturbing. The five-justice conservative majority adopted a one-time-only expansive reading of the Equal Protection Clause that conflicted with their usual narrow interpretation. This was a liberal jurisprudential approach in cynical service of a conservative political outcome: handing the election to George W. Bush.

In this context, Ginsburg's remarks -- like Scalia's duck-hunting -- present a problem, and not just for her. They drag the court down to the level of other political actors, into the partisan muck. They reinforce the public's perception that this game, too, is rigged -- more than it actually is. Evidence of its independence: this term's surprise rulings upholding affirmative action and abortion rights.

Judges aren't the neutral umpires, mechanically calling balls and strikes, of Chief Justice John Roberts' imagining. But they can aspire to that ideal, and should -- on and off the bench.

========

Ruth Marcus' email address is ruthmarcus@washpost.com.

Copyright 2016 Washington Post Writers Group