Will Biden reimpose sanctions on Venezuela? US presidential election muddles decision

Published in News & Features

The United States may decide this week whether to reimpose oil sanctions on Venezuela after strongman Nicolás Maduro violated the terms of an agreement signed in Barbados last year to let opposition candidates run in upcoming presidential elections.

But U.S. domestic politics are complicating the decision.

The Biden administration gave Maduro six months, which are up Thursday, to show he would honor the deal, which was negotiated with support from the United States. However, U.S. officials are struggling to make a decision because they are concerned that immigration and domestic oil prices could be affected as the U.S. heads toward the presidential election in November.

Sources with knowledge of administration discussions said there are ongoing debates among U.S. officials. Some support reimposing sanctions, others are concerned that the impact of sanctions on the South American country’s economy might drive more migration to the U.S., and still others worry about rising oil prices during an election year.

“Domestic context in the United States is critically important,” said Eric Farnsworth, vice president of the Americas Society and Council of the Americas. “You have an election year and concerns about increasing gas prices and migration issues, which are very relevant in the context of Venezuela policy. But we shouldn’t be in this position in the first place because we lifted sanctions prematurely, based on promises that really were never going to be kept by the Venezuelan regime.”

Venezuela, which sits on the largest oil reserves in the world, has been a headache for Republican and Democratic administrations alike as Maduro and his allies have pushed the once-rich country into a spiraling humanitarian crisis, causing the largest migration in the Western Hemisphere’s recent history.

The Trump administration openly sought regime change through a “maximum pressure campaign,” imposing sanctions in 2017 on Venezuelan oil and the regime’s top leaders. The Biden administration has used that leverage to entice Maduro to sit down with the opposition to negotiate a path to free and fair elections despite widespread skepticism.

Those fears have fully materialized, and pressure to reimpose the oil sanctions is mounting.

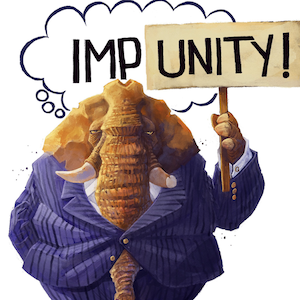

Maduro banned popular opposition candidate Maria Corina Machado from running for president after she got more than 92% of the vote during the opposition primaries in October. He has also moved to block other picks by the opposition’s main political alliance, the Unitary Platform, so he can control who runs — all in violation of the agreement signed in Barbados in October with the opposition and the blessings of the U.S.

Maduro is scheduled to run for president again in the election on July 28, competing only against a small number of little-known opponents. Despite Maduro having a popularity of only 9%, according to polls, regime insiders believe he can easily win, given that the opposition’s vote would be split between the other contenders.

Early on, the U.S. government warned Maduro it would not renew licenses that eased oil sanctions on PDVSA, the Venezuelan state oil company, if he violated the Barbados accord. The relief from sanctions has provided the regime with as much as $3 billion in fresh revenue, according to oil experts from the Venezuelan opposition. Maduro has also taken advantage of the relief to negotiate deals with foreign oil companies in an attempt to boost the country’s output.

Yet the administration has been telegraphing it is considering other options. Under one proposal on the table reported by the Washington Post, the Treasury Department would impose a new sanctions regime allowing Venezuela to continue to sell crude to international customers but in the country’s currency, the bolívar, not hard currencies.

The Maduro regime doesn’t merit “any kind of extension” of the general license granted in October that temporarily allowed transactions involving the Venezuelan oil and gas sectors, said Ryan Berg, director of the Americas Program and head of the Future of Venezuela Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“It’s very clear that they’ve violated almost every single point in the Barbados agreement and what little credibility we have remaining would be completely destroyed if we simply extended that license without any consequences for Maduro,” he said.

Venezuelan observers told the Herald that the three-and-a-half years of the Biden administration’s policies have gained little for the U.S. or the Venezuelan opposition.

“What have we gotten from all of this? Well, I think the facts on the ground speak for themselves; I don’t think Maduro has moved an inch toward free and fair elections,” Farnsworth said.

Some experts argue that Maduro has, in fact, outplayed the administration by gaining concessions and giving up little in return. The administration was able to secure the release of a number of U.S. citizens it deemed had been arrested unjustly in Venezuela in exchange for the release of two of Maduro’s nephews serving a lengthy sentence in New York for drug trafficking and the release of Alex Saab, a key business partner of the ruler who faced money-laundering charges in Miami.

Otherwise, the Venezuelan regime has actually gone backwards in almost all of the other terms it agreed to, increasing the number of people detained as political prisoners and taking steps to fabricate an artificial election victory in July, analysts say.

“Nicolas Maduro has achieved his top priorities: the return of the narco-nephews, the oil licenses, and getting Alex Saab back in Venezuela,” said Eddy Acevedo, a senior advisor at Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. “Maduro will not let Maria Corina Machado [run] and this farce of an election will not be free and fair, so sanctions that Maduro fears and knows will actually bite must be imposed. If not, the US risks losing credibility.”

A State Department spokesperson told the Herald the United States “remains committed to supporting the will of the people and their desire for democratic governance in Venezuela.”

“We continue to urge Maduro and his representatives to allow all candidates to run in inclusive and competitive elections,” the spokesperson said. “We have been clear that we are willing to maintain sanctions relief if Maduro and his representatives uphold their commitments. We don’t have anything to announce.”

A State Department spokesperson told Reuters on Monday the same message although in stronger terms, putting the emphasis on reimposing sanctions if progress is not made.

“I believe it when I see it,” Berg said.

Berg believes that calculations by Biden officials to stabilize Venezuela´s economy to stem migration are misguided, citing data showing that, in the first three months of this year, more Venezuelan migrants traveled through the Darien gap — a perilous stretch of jungle on the borders of Colombia and Panama popular with migrants heading to the U.S.-Mexico border — than during the same period last year.

In an interview with Miami Herald columnist Andres Oppenheimer, Machado warned that Maduro’s victory in July would mean millions more Venezuelans would try to leave the country.

A poll published last week by Venezuelan firm Meganalisis showed that 40% of Venezuelans say they would consider leaving the country if Maduro is declared the winner in the election in July.

“It’s also about the type of regime; it’s about repression at home,” Berg said. “People are leaving repressive conditions. It’s not just about having a little bit of extra oil money on the side or a couple more neighborhoods in Caracas getting some renovations. The numbers haven’t proved that six months of sanctions relief keep Venezuelans in place.”

By focusing on the immigration question, experts argue the administration has given Maduro more leverage. Talking to a Spanish TV station in Miami, Republican Florida Sen. Marco Rubio said last week the Biden Administration “has put us in an extremely difficult position because now Venezuela, through Maduro, is blackmailing the United States” by refusing to accept deportation flights from the U.S.

In a January letter, Rubio, along with Florida Republican Sen. Rick Scott and Republican Louisiana Sen. Bill Cassidy, told Biden, “The time to act is now” to reimpose sanctions on Maduro for breaking the Barbados agreement. But increasingly, the calls to reimpose sanctions are coming from both parties. Maryland Democratic Sen. Ben Cardin issued a joint statement with Rubio and Cassidy last week calling for imposing targeted sanctions on Venezuelan officials responsible for the crackdown on opposition candidates and campaign staffers.

While Biden officials have resisted such calls, experts believe that absent a change in behavior by Maduro, renewed sanctions could at least contain his bad behavior in Venezuela and the region.

“If the purpose of sanctions is to deny resources, raise the costs of oppression, delegitimize the regime in the eyes of not just the global community but the financial community, reduce their ability to conduct their affairs and engage in corruption, identify individuals who are engaged in illegal activities and bring the force of law, the sanctions have worked,” Farnsworth said. “If the sanctions didn’t have any impact, why would the Maduro regime care so much about lifting them?”

Ultimately, if the U.S. doesn’t take any action at this point, Farnsworth asked, “Who’s gonna believe anything we say?”

______

©2024 Miami Herald. Visit miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments