Mike Sielski: Joe and Kobe Bryant were once inseparable. Their deaths bring their bittersweet story to a sad end.

Published in Basketball

PHILADELPHIA — The lasting and most tragic scene from Joe Bryant’s life materialized a month after the death of his son, Kobe. Hundreds of people had filed into the Staples Center in Los Angeles on Feb. 25, 2020, for the memorial service for Kobe and his daughter Gianna. Joe, his wife, Pam, and their daughters, Sharia and Shaya, sat near the front of the arena, but none of the ceremony’s speakers had mentioned them or Wynnewood or Lower Merion High School or much of anything about Kobe’s early life. It was as if Joe and Pam were not there.

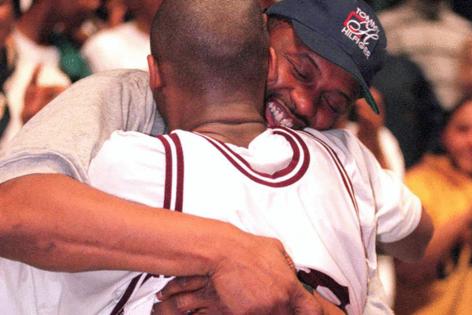

Then, once the service ended, Lower Merion coach Gregg Downer and Jeremy Treatman, an adviser and confidant to Kobe, rushed through the crowd down to Joe and Pam, old friends reuniting and supporting each other in a moment of grief and misery. Among the four of them, there were long, tight hugs and so many tears, and Joe put his hands on Downer’s shoulders and repeated the same phrase to him and Treatman again and again.

“We made a kid for the world,” Joe told them. “We made a kid for the world.”

Joe Bryant died Monday at 69, and he died having lived for the last 4 1/2 years weighed down by the most excruciating might-have-been imaginable. Joe had once been his son’s best friend, his hero, their love so deep that Kobe, as a teenager, used to tell people that he wanted to become the best basketball player in the world to restore the Bryant name to prominence, to give his dad the respect and recognition he deserved yet rarely received.

And Joe Bryant deserved that respect for the player he had been. The best in the Philadelphia Public League in 1972: 27.4 points, 17 rebounds, six assists, and six blocked shots a game for Bartram High. A star at La Salle, averaging more than 20 points and 11 rebounds over his two seasons there. A 6-foot-9 point-forward who could handle the ball like a guard, who was the template for the likes of Magic Johnson and LeBron James, who needed to cross an ocean, to play professionally in Europe after eight years in the NBA, to find the freedom to allow his offensive skills to flourish in full.

No, Joe’s career in the NBA — three teams, including the 76ers, in those eight years, a rep as the kind of guy who’d too often oversleep and miss the team bus — didn’t match his promise. No one could stay angry at him, though. It was impossible. He was a free spirit who got his unforgettable nickname, “Jellybean,” from his love for the candy. Who had a million-watt smile and a gut-busting belly laugh. Who, when he coached girls’ basketball at a Jewish day school on the Main Line, taught his players the ball fakes and flashy footwork that were staples of his game. Who coached the junior-varsity boys team at Lower Merion and was an assistant under Speedy Morris for three years at La Salle.

He didn’t have Kobe’s killer instincts on the court, but he committed himself to guiding his son through the brambles of a life in basketball: how to play on the court, how to carry himself off it. And for all the doubts that people had about Kobe’s decision to skip college, for all the criticism the Bryants took, for all the accusations that they were too arrogant to think Kobe could jump straight to the NBA, no one was more right about who Kobe Bryant was and would be than his father.

“Joe was just a sweetheart of a guy,” Mike Egan, an assistant coach on Lower Merion’s 1995-96 state-championship team, once told me. “One of my favorite memories of all of this was when we won the state title, and Kobe sought him out. They hugged for 60 seconds. They were just so close.”

It should have been a story with the happiest of endings. It was never close to that. Kobe’s relationship with his parents fractured early in his career with the Lakers: disputes over Kobe’s decision to marry his wife, Vanessa, when he was 21 and she was 18; over the sale and handling of some of his personal items and memorabilia; over a young man’s desire to be fully independent after a coddled childhood inside his family’s protective cocoon. Surely, Joe had hoped, had believed deep down, that at some point he and Kobe would mend those wounds and rebuild the bond between them. But once that helicopter — carrying Kobe and Gianna and seven other people — crashed into a Calabasas hillside, that chance and that hope were gone forever.

How does a father go on after that? Does he hang on to the memories that he and his son forged together, or does he force himself to let them go? It was revealed Tuesday that Joe Bryant had suffered a massive stroke last week, but it’s probably truer to say that something else had caused his death.

A broken heart.

____

©2024 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments