Sports

/ArcaMax

Jason Mackey: It's OK to root for new Pirates manager Don Kelly, 'the most regular person alive'

PITTSBURGH — Neil Walker was driving to PNC Park on Sunday morning when the excitement in his voice became even more obvious, the former Pirates second baseman and current broadcaster sounding like he was on his third or fourth cup of coffee.

"He's had other opportunities," Walker said, talking about new Pirates skipper Don Kelly. "But he ...Read more

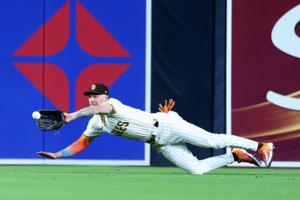

Nightmare ninth inning allows Angels to walk past Padres with win

Jackson Merrill has hit the ground running —literally.

But the Padres’ bullpen continued leaking, and the Angels rallied to beat them 9-5 on Monday night at Petco Park.,

This time, it was closer Robert Suarez who could not do his job.

With a two-run lead that Merrill helped build and preserve, Suarez simply could not throw strikes.

He ...Read more

Giants' cold offense prolongs Verlander's longest winless streak

SAN FRANCISCO — It’s sounding like a broken record.

Justin Verlander, once again, put himself in position to win his first game as a Giant. He pitched six innings and allowed two runs, both on a pair of solo homers by Corbin Carroll. He recorded his fourth quality start in his last five outings, posting a 2.76 ERA over this stretch as ...Read more

Mariners' losing streak reaches four as Yankees pound Emerson Hancock

Julio Rodriguez was, at most, an inch away from taking away Trent Grisham’s first home run in the third inning. The ball, instead, caromed off the tip of center fielder’s glove and just over the T-Mobile Park fence at the deepest part of the yard.

Emerson Hancock was, at most, an inch away from preventing Grisham’s second home run in the ...Read more

Royals offense turns a corner in win over Astros

HOUSTON — The Kansas City Royals were left with a sour taste after dropping a three-game series to the Boston Red Sox last weekend.

The Royals scored just four runs against the Red Sox. On Sunday, Kansas City was held to four hits in a 3-1 loss at Kauffman Stadium.

What a difference a day makes.

The Royals found an offensive rhythm ...Read more

Pirates lose to Mets on Pete Alonso sacrifice fly

NEW YORK — Paul Skenes, pitching in a major market against one of baseball’s best teams, pitched well enough to win. As has happened before, his team didn’t do enough to finish the deal.

The Pittsburgh Pirates lost 4-3 to the New York Mets at Citi Field on Monday night on a walk-off Pete Alonso sacrifice fly in the ninth. Skenes allowed ...Read more

Chase Dollander carries no-hitter into sixth inning, but Rockies falter in Warren Schaeffer's managerial debut

In the first game of the Warren Schaeffer era, Chase Dollander dazzled like the ace he’s proclaimed to be.

But a new manager and the most promising outing yet from the rookie right-hander weren’t enough to flip the script for Colorado. With the offense mostly a no-show, the Rockies lost 2-1 to the Texas Rangers to drop to 7-34 and continue ...Read more

Tigers rout Red Sox 14-2

DETROIT – The Detroit Tigers scored more runs in the third inning against the Boston Red Sox Monday night than they did in the recently-completed three-game series against the Texas Rangers.

Crazy how this game works sometimes.

After being limited to six total runs over the weekend, they sent 14 hitters to the plate and scored nine times in ...Read more

Masyn Winn provides lead and Cardinals' bullpen holds on tight to edge Phillies

PHILADELPHIA — The St. Louis Cardinals had the relievers available they wanted and the matchups they wanted to engineer.

All they needed was to take a lead for a third time.

Masyn Winn provided it.

The Cardinals shortstop lifted a solo home run in the seventh inning to give them their third lead of the game and the one that the bullpen ...Read more

Dave Roberts isn't happy. Rockies fired Bud Black, last limb on Mike Scioscia coaching tree.

LOS ANGELES — When Bud Black was fired as manager of the Colorado Rockies on Sunday, the last limb of the acclaimed Mike Scioscia coaching tree was snapped off and stacked on the mulch pile.

Joe Maddon remains out of work after being fired by the Angels in 2022. Scott Servais was canned by the Seattle Mariners last year. Ron Roenicke hasn't ...Read more

Sean Keeler: Bud Black? Fall guy. If Rockies, Dick Monfort are serious about change, they'll fire GM Bill Schmidt.

DENVER — If the Colorado Rockies were a restaurant, the steaks would bounce. The fish would bite back. You’d need a chainsaw to dent the bread.

With rats roaming the hall, patrons in pain and health inspectors beating down the door, Dick Monfort would fire the maître d’ and declare victory.

The real problem on 20th and Blake wasn’t ...Read more

Kyle Schwarber's two homers, Zack Wheeler's seven scoreless innings lift Phillies to 3-0 win over Guardians

CLEVELAND — For three days last week in Tampa, Fla., the Phillies teed off like the pros at Philadelphia Cricket Club.

Then, they got to Cleveland.

Runs were significantly harder to come by over three games near the banks of the Cuyahoga River. But if ever a series must come down to a pitcher’s duel, it sure does help to have Zack Wheeler ...Read more

Matt Calkins: Mariners' Bryce Miller endures another rough start. Can he right the ship?

SEATTLE — We can’t quantify the pain he feels in his body. But the pain on his face was undeniable.

Perhaps the Mariners’ best pitcher last year, Bryce Miller has gone from lights out to liability.

His ERA through eight starts is 5.22, nearly double the 2.94 he posted last year. His velocity is down, his walks are up — his ability to ...Read more

Yankees ride Ben Rice's grand slam to 12-2 win, take series from A's

Ben Rice swatted a 3-1 offering from Athletics reliever Mitch Spence deep into the right field stands to extend the New York Yankees’ lead in the 5th inning as the Bombers cruised to a 12-2 win, taking the series from the nomadic franchise to boot.

Rice was also plunked twice.

Aaron Judge clubbed four hits on the day to bring his batting ...Read more

Mariners swept by Blue Jays as Bryce Miller struggles again

SEATTLE — You win this round, Canada.

There may not have been quite as many Toronto fans at T-Mobile Park as there have been in years past, but in a time that features some tensions between the United States and its neighbor to the north, the Canadian faithful who did make the trip had plenty to cheer about Sunday as the Blue Jays dispatched ...Read more

Lucas Giolito's gem, Rafael Devers' HR power Red Sox past Royals

Taking their biggest test of the season in this weekend’s road series with the Kansas City Royals, the Boston Red Sox passed with flying colors.

The Royals came into Saturday on a seven-game winning streak, with only two losses in their previous 18 games, and without back-to-back losses since April 19, but it was the Red Sox who took the ...Read more

Tony Gonsolin, Freddie Freeman help Dodgers defeat Diamondbacks

PHOENIX — At the end of a grueling 10-game trek around the country, and in search of their first winning trip this season, the Los Angeles Dodgers got exactly what they needed Sunday afternoon.

A strong start from right-hander Tony Gonsolin. A huge performance from the top of their lineup. And a thorough 8-1 rout of the Arizona Diamondbacks,...Read more

3-run home run by Tim Elko lifts the White Sox to 4-2 victory -- and series win -- against Marlins

CHICAGO — The Chicago White Sox called up Tim Elko on Saturday for a power boost.

It didn’t take long for the designated hitter to deliver.

Elko connected for a go-ahead three-run home run in the sixth inning — the first hit of his major-league career — to lead the Sox to a 4-2 victory against the Miami Marlins on Sunday in front of 16...Read more

Paul Sullivan: Downloading Roku almost as difficult as watching the Cubs' 6-2 loss to the Mets

There will come a day when asking “What’s Roku?” sounds quaint.

Sunday was not that day for some Chicago Cubs fans.

Instead, it was a Mother’s Day morning spent frantically searching for a way to watch the early start between the Cubs and New York Mets.

It was all on the Roku app, which MLB assured fans was free and simple to use. ...Read more

Rockies fire manager Bud Black, bench coach Mike Redmond amid historically bad start

DENVER — The Colorado Rockies fired manager Bud Black on Sunday amid the ballclub’s historically bad start to the season, despite a 9-3 win over the San Diego Padres that snapped an eight-game losing streak. They also fired bench coach Mike Redmond.

The Rockies are 7-33, last in the National League West and own the worst record in Major ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Dave Roberts isn't happy. Rockies fired Bud Black, last limb on Mike Scioscia coaching tree.

- Sean Keeler: Bud Black? Fall guy. If Rockies, Dick Monfort are serious about change, they'll fire GM Bill Schmidt.

- Matt Calkins: Mariners' Bryce Miller endures another rough start. Can he right the ship?

- Tigers rout Red Sox 14-2

- Masyn Winn provides lead and Cardinals' bullpen holds on tight to edge Phillies