Sports

/ArcaMax

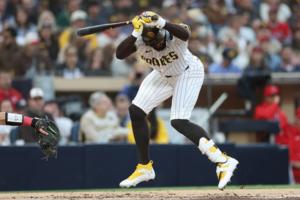

Fernando Tatis Jr.'s walk-off homer saves Padres after another bullpen blow-up

The Padres keep professing faith in their bullpen.

“Why wouldn’t I have the confidence?” manager Mike Shildt said Tuesday afternoon. “I mean, everybody gets a little bit of grace, right? … I mean, track record gives you confidence.”

A few hours later, another Padres reliever continued the bullpen’s ride off the rails.

But the ...Read more

Koss' grand slam leads SF Giants' three-homer day to break cold spell

SAN FRANCISCO — The Giants carried two starkly different trends into Tuesday. They’d never lost a game where Robbie Ray started. They’d also never won a game with their new City Connect jerseys.

Something had to give. By night’s end, their four-game losing streak was a remnant of the past.

Christian Koss hit a grand slam for his first ...Read more

Brett Baty homers, Kodai Senga battles in Mets win over Pirates

NEW YORK — Maybe this isn’t exactly what the New York Mets envisioned when they drafted Brett Baty in the first round of the 2019 draft, and his timeline certainly isn’t what the club envisioned. But Baty has finally blossomed from prospect to big leaguer.

The second baseman/third baseman broke a tie in the bottom of the seventh inning to...Read more

Rockies' offense AWOL again in 4-1 loss to Rangers

The director might have changed, but the Rox Show looks the same.

In their second game under interim manager Warren Schaeffer, the Colorado Rockies’ offense was once again a no-show in a 4-1 loss to the Texas Rangers on Tuesday night at Globe Field. Schaeffer was named interim manager on Sunday when Bud Black was fired.

The Rockies ...Read more

Mitch Keller's dominant start again wasted by Pirates' futile hitting against Mets

NEW YORK — Manager Don Kelly shuffled the Pittsburgh Pirates’ lineup on Tuesday night, likely hoping some changes would change the Pirates’ offensive fortunes.

Those changes had little effect. The Pirates lost to the New York Mets 2-1 on a rainy Tuesday at Citi Field. The Pirates have now scored four or fewer runs in 19 consecutive games,...Read more

Rays blow lead, rally in 9th, then hang on to beat Blue Jays

There were several points Tuesday when it appeared the Rays did enough to beat the Blue Jays.

But it wasn’t until rookie reliever Mason Montgomery retired Daulton Varsho, who had already homered twice, with two on to end it that they did, 11-9.

After taking an early 4-0 lead and carrying a 6-4 advantage into the eighth, the Rays saw it go to...Read more

Tigers' Báez hits three-run homer in 11th inning to beat Red Sox

DETROIT – The Javier Báez renaissance is real.

Báez's second three-run home run of the night, this one in the bottom of the 11th, gave the Tigers a dramatic, walk-off 10-9 win over the Boston Red Sox at Comerica Park.

His three-run homer in the sixth had put the Tigers up 6-4.

The Red Sox had taken a 9-7 lead in the top of the 11th when...Read more

Kris Bubic shines again, but Royals fall to Astros, 2-1, on walk-off homer

HOUSTON — Kansas City Royals starter Kris Bubic continued his torrid start to the 2025 campaign Tuesday night against the Houston Astros, but it wasn't enough as the Royals fell, 2-1.

Bubic limited the Astros to one run across 6 1/3 innings. He allowed six hits and added nine strikeouts in his ninth start of the season.

Houston (21-20) ...Read more

Patrick Saunders: Bud Black's firing was inevitable, but messy -- even by the Rockies' standards

DENVER — Sunday was a bizarre day at Coors Field, even by Rockies standards.

The club’s decision to fire manager Bud Black was no surprise. It was like a thunderstorm building over the Rockies. Anyone paying attention could see it coming. Big league managers don’t survive 7-33 starts after back-to-back 100-loss seasons.

Black surely saw ...Read more

Paul Zeise: Pete Rose and 'Shoeless' Joe Jackson are reinstated. Now put them both in the Hall of Fame.

PITTSBURGH — Rob Manfred removed Pete Rose and “Shoeless” Joe Jackson from the permanent ban list, which means both men are now eligible for the Hall of Fame. In total, Manfred removed 16 players, all deceased (including Rose and Jackson) and one deceased owner from the lifetime ineligible list.

It marks maybe the first time I have ...Read more

Royals sign 45-year-old MLB veteran Rich Hill to minor league deal

HOUSTON — The Kansas City Royals are always in search of quality pitching. On Tuesday, the Royals landed an experienced veteran in left-hander Rich Hill.

Hill, 45, signed a minor league deal with the Royals. He will report to the Royals' spring training complex in Surprise, Ariz., before eventually joining Triple-A Omaha.

“We were looking ...Read more

Bill Shaikin: Anaheim wants an Angel Stadium deal. Angels fans see inspiration in San Diego.

ANAHEIM, Calif. — Alicia Mink wanted to see her Angels play Monday. She never had been to Petco Park.

"Super nice," she said. "Love the stadium."

Petco Park is the best ballpark in Southern California, by far — integrated into a vibrant neighborhood; spacious and modern; packed with delectable food and drink options; a community gathering ...Read more

Pete Rose is now eligible for the Hall of Fame. But that doesn't mean he'll get the votes for induction.

Let’s be clear: It was quite a thing Tuesday that Pete Rose’s name — 16 others’, too, including “Shoeless” Joe Jackson’s — was posthumously removed from Major League Baseball’s permanently ineligible list.

But it was only one thing.

Because although commissioner Rob Manfred’s landmark decision that a lifetime ban lasts only...Read more

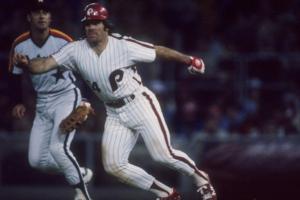

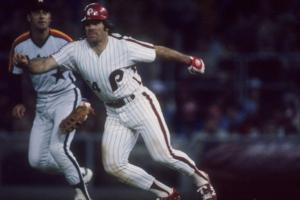

Marcus Hayes: Donald Trump gets former Phillies star Pete Rose's permanent ban lifted. So, what's in it for Trump?

PHILADELPHIA — Our bizarre president wanted the Gulf of Mexico renamed the “Gulf of America,” wanted to rename Veterans Day to “Victory Day for World War I,” and now wants to redefine the word “permanent.”

Well, like former Phillies star Pete Rose on a typical day at bat, President Donald Trump‘s 1 for 3.

In February, shortly ...Read more

Pirates' Paul Skenes to pitch for Team USA in 2026 World Baseball Classic

NEW YORK — The Pirates' best player intends to showcase his talent on an international stage.

In an appearance on MLB Network, Pirates ace Paul Skenes announced his commitment to Team USA for the 2026 World Baseball Classic.

"When I was coming through high school, the thing that I thought I was going to be doing right now was flying jets ...Read more

Pete Rose, 'Shoeless' Joe Jackson reinstated by Major League Baseball, making Hall of Fame election possible

LOS ANGELES — Pete Rose was posthumously removed from Major League Baseball’s permanently ineligible list Tuesday, making the all-time hits leader eligible for induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

“Shoeless” Joe Jackson, banned after his participation in the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, also was reinstated in a sweeping ...Read more

Pete Rose reinstated by Major League Baseball, which makes Hall of Fame election possible

LOS ANGELES — Pete Rose was posthumously removed from Major League Baseball’s permanently ineligible list Tuesday, making the all-time hits leader eligible for induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Rose had been exiled from the sport since 1989, after he was found by then-commissioner Bart Giamatti (yes, the father of actor ...Read more

Jason Mackey: It's OK to root for new Pirates manager Don Kelly, 'the most regular person alive'

PITTSBURGH — Neil Walker was driving to PNC Park on Sunday morning when the excitement in his voice became even more obvious, the former Pirates second baseman and current broadcaster sounding like he was on his third or fourth cup of coffee.

"He's had other opportunities," Walker said, talking about new Pirates skipper Don Kelly. "But he ...Read more

Nightmare ninth inning allows Angels to walk past Padres with win

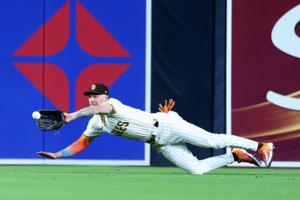

Jackson Merrill has hit the ground running —literally.

But the Padres’ bullpen continued leaking, and the Angels rallied to beat them 9-5 on Monday night at Petco Park.,

This time, it was closer Robert Suarez who could not do his job.

With a two-run lead that Merrill helped build and preserve, Suarez simply could not throw strikes.

He ...Read more

Giants' cold offense prolongs Verlander's longest winless streak

SAN FRANCISCO — It’s sounding like a broken record.

Justin Verlander, once again, put himself in position to win his first game as a Giant. He pitched six innings and allowed two runs, both on a pair of solo homers by Corbin Carroll. He recorded his fourth quality start in his last five outings, posting a 2.76 ERA over this stretch as ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Mitch Keller's dominant start again wasted by Pirates' futile hitting against Mets

- Kris Bubic shines again, but Royals fall to Astros, 2-1, on walk-off homer

- Marcus Hayes: Donald Trump gets former Phillies star Pete Rose's permanent ban lifted. So, what's in it for Trump?

- Rays blow lead, rally in 9th, then hang on to beat Blue Jays

- Tigers' Báez hits three-run homer in 11th inning to beat Red Sox