Sports

/ArcaMax

Bill Madden: What's up with these contract extensions for some of MLB's top young stars?

NEW YORK — As the clubs all broke from the starting gates this season, there was an interesting development that no one can quite put a finger on, other than independent coincidence: No less than a half dozen of baseball’s brightest young stars all signed lucrative multi-year contract extensions that will take each of them well beyond their ...Read more

Rockies pull off triple play but lose to A's at Coors Field

DENVER — Ryan McMahon pumped his fist, German Marquez let loose with a roar and Michael Toglia flashed a little kid’s grin. Good times.

Then it all fell apart.

In the second inning, the Rockies pulled off the fifth triple play in franchise history.

But the Rockies blew a 3-0 lead and lost, 7-4, to the Athletics on Saturday night at Coors ...Read more

Chapman delivers on bobblehead night as Giants extend win streak to six

SAN FRANCISCO — Long live the power of the Bobblehead Night.

On an evening where the San Francisco Giants distributed 15,000 bobbleheads bearing Matt Chapman’s likeness, the five-time Gold Glove Award winner totaled two doubles, two RBIs and two runs scored, then turned in a vintage defensive gem to end the game. The Giants beat the Seattle...Read more

Francisco Lindor's walk-off sacrifice fly caps Mets' comeback win over Blue Jays

NEW YORK — For nearly eight innings Saturday, the New York Mets squandered scoring opportunity after scoring opportunity.

They started 0 for 10 with runners in scoring position and left a runner stranded at third base in three of the first seven frames.

But the Mets would not be denied.

Francisco Lindor’s walk-off sacrifice fly in the ...Read more

Yankees' Trent Grisham continues to capitalize on playing time, homers twice in win over Pirates

PITTSBURGH — After hitting his first home run of the 2025 season on April 3, Trent Grisham noted that “getting consistent at-bats” has factored into his hot start.

The 28-year-old barely played for the Yankees in 2024 after joining the team in the Juan Soto trade. A starter throughout his career, the Gold Glove center fielder hit .190 ...Read more

Orioles' Sugano earns first MLB win, 8-1 over Royals

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Entering this season, the Baltimore Orioles’ rotation was expected to be this team’s weak spot.

Without ace Corbin Burnes and with budding aces Kyle Bradish and Grayson Rodriguez on the injured list, Baltimore’s rotation was without the same firepower it had in years past.

How much of a problem the rotation will be ...Read more

Red Sox game postponed, doubleheader scheduled for Sunday

BOSTON — Saturday’s Red Sox game against the St. Louis Cardinals has been postponed due to inclement weather, the club announced.

The game has been rescheduled as the first game of a split doubleheader on Sunday, April 6, and will begin at 1:35 p.m. ET. Tickets for Saturday’s game will be good for admission to Sunday’s early game, and ...Read more

Roki Sasaki shows glimpses of his future star potential in Dodgers' win vs. Phillies

PHILADELPHIA — The Dodgers, as manager Dave Roberts had said repeatedly when asked about Roki Sasaki over the season's first few weeks, knew what they signed up for.

When they signed the 23-year-old Japanese phenom this offseason, the Dodgers were mesmerized with Sasaki's stuff; from his upper-90s mph fastball to a forkball-grip splitter that...Read more

Nick Pivetta roughed up as Padres drop second straight to Cubs

CHICAGO — It was a 180-degree turn for the worse for Nick Pivetta on Saturday, and that is pretty much what has happened to the Padres over the past two games as well.

Pivetta’s first start with his new team was one of the highlights in a 7-0 launch to the Padres’ season, during which they forced the action on the bases, played sterling ...Read more

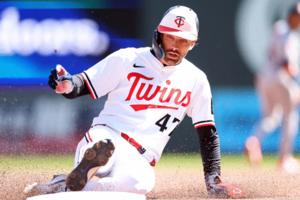

Twins ride six-run fourth inning to 6-1 victory against Astros

MINNEAPOLIS — It’s hard to say the Twins’ offense is fixed, or cured, or found, not when they failed to scratch out a hit in their first three turns at bat Saturday, and their last three, too.

But if they can pile up five hits, six runs and seven baserunners in one inning, at least they can make the other ones irrelevant.

José Miranda ...Read more

Alex Cora has unique plan to maximize Kristian Campbell's versatility

BOSTON — Boston’s last true everyday second baseman was Dustin Pedroia, nearly a decade ago and before Alex Cora began managing the team in 2018.

The Red Sox have since endured a revolving door of infielders, including Ian Kinsler, Eduardo Nuñez, Brock Holt, José Peraza, Christian Arroyo and Bobby Dalbec, and lost too many games to count ...Read more

Malloy's bat sparks Tigers offense to second straight win over White Sox

DETROIT — Justyn-Henry Malloy doesn’t seem like a prototypical leadoff hitter, at least not in any old-school sense. But he has certainly produced like one.

In his first start at the top of the order last Monday in Seattle, after he was hastily summoned early that morning from Toledo, he ignited the offense with a leadoff double, an RBI ...Read more

Everyone is intrigued by the torpedo bat, including the Phillies. Will it be a revolution or a fad?

PHILADELPHIA — Bryson Stott doubled, homered, walked twice, scored three runs and drove in two in the Phillies' victory last Saturday in Washington. By any standard, it was a satisfying day at the plate.

Then, he heard about what the Yankees did.

Everybody heard. Nine home runs — repeat: nine home runs — for one team in a single game ...Read more

How 'torpedo' bats became the fascination of baseball -- even for ex-Dodger Eric Gagné

LOS ANGELES — In his playing days, Eric Gagné's objective was simple.

"My job was to break bats," the former Dodgers closer, and 2003 Cy Young Award winner, joked with a laugh.

Which makes his current occupation, as the CEO of Quebec-based bat company B45, a little more than ironic.

"Now my job is to make sure the bats don't break anymore,...Read more

Walks and injuries spoil Angels' home opener

ANAHEIM, Calif. — On the night the Angels and a sellout crowd of 44,749 celebrated a new season and new hope, sparked by an encouraging first road trip, their performance was frustratingly familiar.

The Angels lost, 8-6, to the Cleveland Guardians in the home opener, a game marked by walks, a defensive misplay, missed run-scoring ...Read more

Orioles' defense unravels in 8-2 loss to Royals

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Through the first two innings Friday, the Orioles scored twice as many runs versus the Royals than they did in two games against them in last season’s American League wild-card series.

The only problem was the result was the same: a loss.

Dean Kremer struggled to get swing and misses, his defense let him down and ...Read more

Dodgers suffer their first loss after ninth-inning rally sputters vs. Phillies

PHILADELPHIA — To many around the sport, the Dodgers have become villains for the way they’ve outspent the rest of the league, loaded their roster with international talent, and stockpiled depth at seemingly every position.

To the Phillies, however, it makes them the standard; one with which their own big-money, star-studded roster is ...Read more

Yankees spoil sloppy Pirates' opener as Pittsburgh fans beg, 'Sell the team'

PITTSBURGH — The last time Oswaldo Cabrera and the Yankees visited the Steel City, he stopped by the Roberto Clemente Museum.

The visit, taken in September 2023, included a chance to hold one of Clemente’s enormous bats. There’s a belief that players who visit the museum and hold the humanitarian’s bats are graced with good luck. Sure ...Read more

Punchless Rockies lose frigid home opener to A's in 11 innings

DENVER — An announced sellout crowd of 48,105 braved snow and frigid temperatures for the home opener at Coors Field Friday afternoon.

The Rockies gave them a cold shoulder, losing 6-3 to the Athletics in 11 innings in a game that took 3 hours and 21 minutes. The A’s won the game with a two-out, two-run double to right by Gio Urshela off ...Read more

Adames hits walk-off, two-run single in home debut as Giants beat Mariners in 11 innings, 10-9

SAN FRANCISCO — The pregame scene at Oracle Park on Friday afternoon — originally known as Pacific Bell Park when it opened 25 years ago — was an exercise in nostalgia.

The jumbotron featured a montage of the best moments in the ballpark’s two and a half decades, from Barry Bonds’ milestone homers to Matt Cain’s perfect game to the ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Chapman delivers on bobblehead night as Giants extend win streak to six

- Yankees' Trent Grisham continues to capitalize on playing time, homers twice in win over Pirates

- Francisco Lindor's walk-off sacrifice fly caps Mets' comeback win over Blue Jays

- Orioles' Sugano earns first MLB win, 8-1 over Royals

- Red Sox game postponed, doubleheader scheduled for Sunday