Newly discovered photos of Nazi deportations show Jewish victims as they were last seen alive

Published in Political News

The Holocaust was the first mass atrocity to be heavily photographed.

The mass production and distribution of cameras in the 1930s and 1940s enabled Nazi officials and ordinary people to widely document Germany’s persecution of Jews and other religious and ethnic minorities.

I co-direct an international research project to collect every available image documenting Nazi mass deportations of Jews, Roma and Sinti, as well as euthanasia victims, in Nazi Germany between 1938 and 1945. The most recently discovered series of images will be unveiled on Jan. 27, 2025 – Holocaust Remembrance Day.

In most cases, these are the very last pictures taken of Holocaust victims before they were deported and perished. That fact gives the project its name, #LastSeen.

A few of the images we’ve tracked down were taken by Jewish people, not Nazi officials, offering a rare glimpse of Nazi mass deportations from a victim’s perspective. As descendants of survivors help our researchers identify the deportees in these images and tell their stories, we give previously faceless victims a voice.

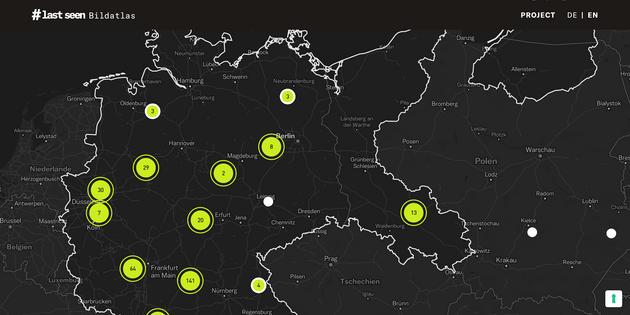

The #LastSeen project is a collaboration between several German academic and educational institutions and the USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research in the United States. When it began in late 2021, researchers knew of a few dozen deportation images of Jews from 27 German towns that had been gathered for a 2011-2012 exhibition in Berlin.

After contacting 1,700 public and private archives in Germany and worldwide to find more, #LastSeen has now collected visual evidence from 60 cities and towns in Nazi Germany. Of these, we’ve analyzed 36 series containing over 420 images, including dozens of never-before-seen photo series from 20 towns.

Most photographs of Nazi mass deportations from local archives published in our digital atlas were taken by the perpetrators, who documented the event for the police or municipality. That has heavily shaped our visual understanding of these crimes, because they display victims as a faceless mass. When individuals were depicted, it was most often through an antisemitic lens.

We have, however, obtained a handful of images taken from a victim’s perspective. In January 2024, the #LastSeen team shared newly discovered photographs showing the Nazi deportations in what was then Breslau, Germany – today Wroclaw, Poland.

They were sent to us for analysis by Steffen Heidrich, a staff member of the Regional Association of Jewish Communities in Saxony, Germany, who came across an envelope titled “miscellaneous” while reorganizing his archive. It contained 13 deportation photographs – the last images taken of dozens of Jewish victims before they were transported from Breslau to Nazi-occupied Lithuania and massacred in November 1941.

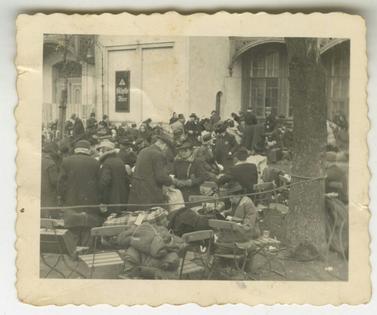

Many of these pictures in this series show a large, mixed age group of men and women wearing the yellow star – the notorious Nazi-mandated sign for Jews – gathering outside with bundles of their belongings. Some are taken from a peculiar angle, from behind a tree or a wall, suggesting they were snapped clandestinely.

Given the deportation assembly point for the Breslau Jews, a guarded local beer garden, our researchers knew that only a person with permission to access that property could have shot these pictures.

For these two reasons, we concluded that an employee of the Jewish community of Breslau must have documented the Nazi crimes – most likely Albert Hadda, a Jewish architect and photographer who clandestinely photographed the November 1938 pogrom in Breslau.

Hadda’s marriage to a Christian partially protected him from persecution. Between 1941 and 1943, the city’s Jewish community tasked him with caring for the deportees at the assembly point until their forced removal.

These 13 recently discovered pictures constitute the most comprehensive series illuminating the crime of mass deportations from a victim’s perspective in Nazi Germany. Their unearthing is testimony to the recently rediscovered widespread individual resistance by ordinary Jews who fought Nazi persecution.

Our project has also identified new deportation photos taken in the German town of Fulda in December 1941, during a snowstorm.

Previously, historians knew of only three pictures of this deportation event. Preserved in the city archive, they show the deportees at the Fulda train station during heavy snowfall.

We discovered two new images of the same Nazi deportation, apparently taken by the same photographer, in a videotaped survivor interview in the Visual History Archive of the USC Shoah Foundation in Los Angeles.

In 1996, the Shoah Foundation interviewed Miriam Berline, née Gottlieb, the daughter of a successful Orthodox Jewish merchant in Fulda. At the end of the two-hour interview, Berline held two photographs up to the camera. They clearly show the same snowy deportation in Fulda.

Berline, born in 1925, escaped Nazi Germany in 1939. She did not remember how her family obtained the images but recalled the photographer as Otto Weissbach, a “wonderful” man who had helped Fulda’s Jewish families.

Our researchers investigated and learned his name was Arthur Weissbach, a non-Jewish neighbor of the Gottliebs. The factory he owned still exists. Descendants of Jewish families have since confirmed that he kept valuables for them and took care of elderly relatives who stayed behind.

Weissbach’s niece said he was a passionate hobby photographer. Since Weissbach kept contact with survivors after the war, he might have given the images to the Gottlieb family. Today, the family’s copies are lost, but their existence is preserved in Berline’s video interview at the USC Shoah Foundation.

The pictures show the Jews at the Fulda train station on Dec. 9, 1941 – revealing how Nazi deportations happened in plain view.

The day before, Jewish men and women from around Fulda had been summoned and spent the night at a local school gym. In the morning, they were taken to the train station and forced by police to board a train to Kassel, in central Germany, and then eastward onto Riga, in Nazi-occupied Latvia.

In total, 1,031 Jews were deported from Kassel to Riga. Only 12 from Fulda survived.

It is difficult to identify the people in the photos we discover. So far, we’ve published 279 biographies in the digital atlas.

In the future, artificial intelligence may help us identify more people from the photos in our collection. But for now, this process takes exhaustive research with the help of local researchers and descendants of survivors, whose names are known from archived transport lists.

Families often struggle to recognize individuals in these images, but sometimes they have family photos that help us do so.

Take, for example, this posed family portrait of two young girls. They are Susanne and Tamara Cohn.

Relatives of the Cohn family had this photo. It, along with data from the local Nazi transport list, established that two girls photographed in one of his Breslau deportation shots were the daughters of Willy Cohn.

Cohn, a well-known German-Jewish medieval historian and high school teacher in Breslau, kept a detailed diary about the persecution of the town’s Jews from 1933 to 1941. It was unearthed and published in the 1990s.

This photo, below, may be the last picture ever taken of his children with their mother, Gertrud.

The #LastSeen research project is generating new insights into the history of Nazi mass deportations, new methodologies for photo analysis and new tools for Holocaust education.

In addition to the digital atlas, which has been visited by more than 50,000 people since its launch in 2023, we have developed several award-winning educational tools, including an online game that invites students to search for clues, facts and images of Nazi deportations in an artificial attic.

In workshops for teachers and seminars with students, #LastSeen teaches the history of Nazi deportations and demonstrates how historical photo research works. In Fulda, for example, high schoolers helped us locate the exact places where the photographs were taken.

Those pictures will be published in our atlas on Holocaust Remembrance Day 2025. A public commemoration in Fulda will feature the local students’ contributions.

Depending on fundraising, we hope to extend the #LastSeen project beyond Germany. Collecting images from all 20-plus European countries annexed or occupied by the Nazis will help us better understand these crimes and advance research and education in new ways.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Wolf Gruner, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Read more:

Descendants of Holocaust survivors explain why they are replicating Auschwitz tattoos on their own bodies

Why we need to rethink how to teach the Holocaust

Digital technology offers new ways to teach lessons from the Holocaust

Wolf Gruner is the director of the USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide, which is a partner of the multiinstitutional research project #LastSeen.

Comments