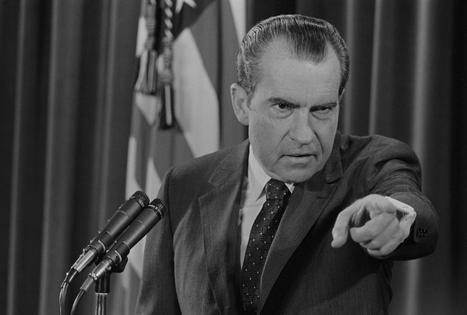

Nixon’s official acts against his enemies list led to a bipartisan impeachment effort

Published in Political News

The Nixon administration’s enemies list inspired bipartisan revulsion. Its purpose was, in the immortal words of President Richard Nixon’s White House counsel, to “use the available federal machinery to screw our political enemies.”

The revelation of the list’s existence during the Watergate hearings of 1973 provoked conservative columnist and Nixon supporter William F. Buckley Jr. to use the f-word in print. Yes, Buckley called the enemies list “an act of proto-fascism. It is altogether ruthless in its dismissal of human rights. It is fascist in its reliance on the state as the instrument of harassment.”

But that was then. Now, Donald Trump has announced his intention to place in charge of the FBI someone who published an enemies list in a 2023 book.

Kash Patel’s “Government Gangsters” includes a list of “Members of the Executive Branch Deep State,” which he describes as “a cabal of unelected tyrants who think they should determine who the American people can and cannot elect as president.”

Despite that description, the list does not include anyone who tried to keep Trump in office illegally after he lost in 2020. It does, however, include a number of high-level Trump appointees who chose not to help him in that effort to overturn democracy.

Targeting fellow Republicans follows Nixonian precedent. The top name on an early draft of Nixon’s enemies list was a Republican who worked in the Nixon White House on Henry Kissinger’s National Security Council staff.

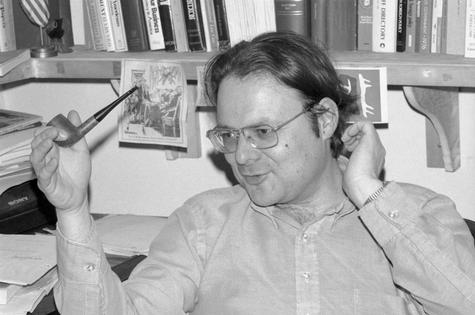

The story of that aide, Morton H. Halperin, demonstrates the dangers of enemies lists to their makers as well as their targets. I tell this story in my book “Chasing Shadows: The Nixon Tapes, the Chennault Affair, and the Origins of Watergate.”

Morton Halperin committed no crime.

To Nixon and Kissinger, however, he was the man who knew too much. They mobilized the police power of the state against him, because they feared what he could reveal about them.

Kissinger, as national security adviser, had told Halperin about the secret bombing of Cambodia. The waves of B-52 attacks on North Vietnamese infiltration routes was no secret to the Cambodians, but Nixon and Kissinger kept it from the American people. The New York Times, however, soon found out and ran a front-page story about the bombing campaign.

Looking for the leaker, Nixon had FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover tap Halperin’s phone. The wiretap never produced any evidence against Halperin, but Nixon continued it even after Halperin resigned from the White House and became an adviser to the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination, Maine Sen. Edmund S. Muskie.

At that point, the Halperin wiretap became a way for Nixon to spy on top Democrats, including former Defense Secretary Clark Clifford, who had served as an adviser to Democratic Presidents Harry Truman, John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Hoover reported to the White House on a conversation Halperin had with Leslie Gelb, another Muskie adviser, about an article Clifford was writing for Life magazine criticizing Nixon on Vietnam.

There was nothing remotely illegal about criticizing the president, of course, but the FBI director sent the information to the White House anyway.

“This is the kind of early warning we need more of,” chief domestic adviser John Ehrlichman wrote White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman. “Your game planners are now in an excellent position to map anticipatory action.”

The FBI is not supposed to be a political intelligence operation, secretly helping the president plan moves against his critics. In this case, it was.

The keepers of Nixon’s enemies lists – there was more than one – added the names of Gelb and Clifford.

Nixon didn’t fully weaponize the state against Halperin until the 1971 leak of the Pentagon Papers, a top secret Defense Department history of America’s involvement in Vietnam.

Nixon persuaded himself that Halperin and Gelb were part of a conspiracy that was leaking the papers as a warmup to leaking Nixon’s own damaging secrets during his 1972 reelection campaign.

This wasn’t true. Halperin’s and Gelb’s involvement with the Pentagon Papers was innocent. Halperin oversaw the study as deputy assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs in the Johnson administration, and Gelb was the study’s day-to-day supervisor as director of policy planning and arms control.

They let Daniel Ellsberg read it in 1969, when he was doing work on Vietnam for the government, but they didn’t know he was going to leak it. Not even Ellsberg knew it at the time; he decided much later. Ellsberg leaked the papers without informing Halperin or Gelb.

None of this made a difference to Nixon. He hated Jews, intellectuals and Ivy Leaguers, and Halperin and Gelb were all three. So was Kissinger, of course, but Nixon made exceptions for those who continually demonstrated their devotion to him.

Having convinced himself that Halperin and Gelb were conspiring against him, Nixon resolved to conspire against them.

Nixon ordered his aides to break into the Brookings Institution, where Halperin and Gelb then worked, because he believed – mistakenly – that they were keeping classified documents there.

To commit this and other crimes, Nixon created the Special Investigations Unit, later known as the Plumbers. The Brookings burglary did not take place, but the Plumbers did break into the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist seeking evidence of a conspiracy. They came up empty-handed.

Being on Nixon’s enemies list did not break Halperin. He went on to testify as a defense witness in Ellsberg’s trial for leaking the Pentagon Papers and became director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Washington office. If, as the saying goes, a conservative is a liberal who’s been mugged, perhaps a civil libertarian is a Republican whose phone has been tapped.

Nixon’s illegal wiretaps and Plumbers operation ultimately became part of an article of impeachment against him. The House Judiciary Committee passed the article by 28 to 10, with seven Republicans joining the committee’s Democratic majority on July 29, 1974, less than two weeks before Nixon resigned rather than face impeachment and conviction.

Things are different now. In Trump’s first term, the vast majority of congressional Republicans proved unwilling to impeach or convict him. He will begin his second term armed with a Supreme Court decision declaring him immune from criminal prosecution for most “official acts.”

Almost all of Nixon’s abuses of power could be described as “official acts,” which should give everyone an idea what the Supreme Court has unleashed on the republic.

Though circumstances are different, Nixon’s enemies list does have a lesson to teach us today. An enemies list isn’t a weapon against “the Deep State.” An enemies list was a tool that a president used to create a deep state of his own.

Nixon’s Plumbers operated above the law, outside the U.S. Constitution, and beyond accountability to anyone other than him. Nixon used the government as a weapon against the targets of his hatred.

This is why conservatives like Buckley abominated the enemies list: “It is fascist in its automatic assumption that the state in all matters comes before the rights of the individual.”

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Ken Hughes, University of Virginia

Read more:

Supreme Court’s ruling in Trump v. United States would have given Nixon immunity for Watergate crimes — but 50 years ago he needed a presidential pardon to avoid prison

The weaponization of the federal government has a long history

How democracy gets eroded – lessons from a Nixon expert

Ken Hughes is a research specialist with the Presidential Recordings Program of the University of Virginia's Miller Center, whose work is funded in part by grants from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.

Comments