I’m a Scholar of White Supremacy Who’s Visiting all 113 Places Where Confederate Statues Were Removed in Recent Years − Here’s Why Richmond Gets it Right

Published in Political News

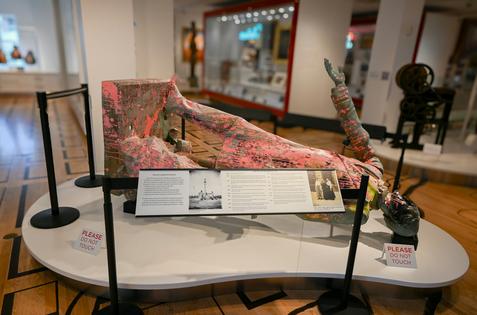

In a symbolic rebuke of the American South’s racist history, an old Confederate monument now has a meaningful new life, four years after it was toppled in Virginia.

In June 2020, protesters in Richmond used ropes to pull down the bronze statue of Confederate leader Jefferson Davis, splashed paint on its surface and slung a toilet paper noose around its neck. Charged discussions over what should become of it followed.

In 2022, the statue – carefully and controversially preserved in its degraded state and displayed on its back instead of its original upright position – went on display in a Richmond museum.

This year I visited the Davis statue in its new home. I am traveling to each of the 113 communities that removed or relocated Confederate symbols between 2015 and 2023 during the national reckoning sparked by the Black Lives Matter movement. As a sociologist who studies legacies of historical conflict, my goal is to understand how those sites – and the objects that for decades stood upon them – are reshaping where and how the Confederacy bears upon the nation’s current identity.

Seven of the Confederate statues taken down over the past decade commemorated Jefferson Davis. A Mississippi congressman and U.S. secretary of war, Davis led the Confederacy between 1861 and the end of the Civil War four years later.

Before it was damaged and pulled down by activists in 2020, Richmond’s 8-foot bronze rendering of Jefferson Davis occupied a premier plot on the city’s famed Monument Avenue. Standing in front of a 60-foot Doric column, the statue proclaimed the president of the Confederacy a heroic “exponent of constitutional principles” and “defender of the rights of state.”

Now the Davis statue is at The Valentine – a museum that occupies the site of the studio where the statue was sculpted in 1903. Curators there have gone to great lengths to conserve the monument in its “2020 state.” The pink paint covering much of its surface, toilet-paper noose and gleaming bronze surfaces – uncovered upon impact with the ground – remain.

These details offer physical evidence of protesters’ challenge to the city leaders who erected the statue. Richmond put it up 50 years after the Confederacy’s fall, with a plaque calling the Civil War an “unflinching struggle against overwhelming odds,” fought “to clothe their country with freedom.”

Such ostensibly lofty principles reflect the “Lost Cause” myth advanced by groups such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which helped to fund and place the monument in 1907. This Lost Cause account obscures the fact that Confederates, in fact, seceded from the Union to defend and perpetuate slavery.

Moving the statue from its public perch on Monument Avenue and into a museum transformed it from a commemorative object glorifying its subject to a historical artifact. And presenting the statue in its prone and damaged state makes its removal the center of that historical story.

Indeed, this unscrubbed statue still allows viewers to consider why Davis was celebrated in the first place. But they can no longer avoid reckoning with those who refused to allow him to remain standing.

Monuments removed entirely from public view quickly fade from public memory, as my 2022 study with Christina Simko and Nicole Fox found. Moving them to alternative sites, meanwhile, enables public conversation about them to continue.

Our research casts doubt on claims that movements against Confederate symbols seek to “erase history.” But who guides this process is pivotal to a full and honest appraisal of the histories that these objects embody.

An hour’s drive south of Richmond presents a sharply opposing case. That’s where another Confederate statue has been claimed by a local resident and displayed in a fenced area on the edge of a cornfield.

Its interpretative marker, installed as part of the cornfield display in 2021 after the statue was removed from the grounds of the nearby Isle of Wight County courthouse, has a critical bent. Yet its critique is not of Confederate supporters of enslavement.

“By 2020,” the marker reads, “historical monuments and memorials on public land were allowed to be vandalized and destroyed in many localities. It was decided by those who wanted to protect this monument that it should be taken out of government ownership and control.”

The government courthouse itself fails to counter this challenge. The monument’s original site includes no trace or mention of the statue that once resided there or why it was removed.

That lack of recognition remains the case with the majority of removed Confederate monuments. But a handful of other Virginia communities beyond Richmond do now provide a space for the public to grapple with these histories.

Warwick County’s courthouse in Newport News includes a weatherproofed display panel telling the story of the Confederate monument that once stood there and explaining why and how county officials responded to activists’ calls to remove and place it in storage.

A cemetery in Hampton has added a plaque to the obelisk of its Confederate soldier’s statue that reframes the significance of the Civil War. It was, the plaque says, the beginning of “the path to freedom for millions of people who had been enslaved.”

And in Roanoke, a statue of Henrietta Lacks, whose “immortal” cell sample taken shortly before her death in 1951 continues to transform medical research, now stands where a monument to Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee once stood. The Lee statue remains on view, but in a cemetery 2 miles down the road.

These approaches represent different and sometimes conflicting narratives about removed monuments. But the fates of all these statues and their grounds illustrate an unfolding movement to recast the connections between the past and today.

Who defines American values? In their respective reckonings with the Confederacy – and with modern racial justice movements – relocated Confederate statues are bellwethers of ongoing struggles to resolve this question.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: David Cunningham, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

Read more:

Jan Smuts was a white supremacist. Nelson Mandela a black liberation hero. New book explores what they have in common

Racism is such a touchy topic that many US educators avoid it – we are college professors who tackled that challenge head on

‘Yellowstone’ highlights Montana’s long-forgotten connection to the Confederacy

David Cunningham does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments