Commentary: Why Trump's mass deportation plan is a lost cause

Published in Political News

Immigration, especially that of undocumented migrants, is a key issue — perhaps the key issue — in the presidential race.

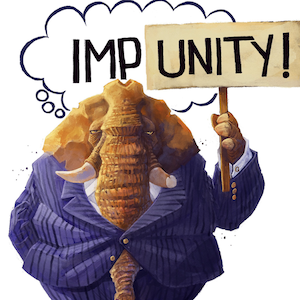

Despite the Biden administration's efforts to strengthen border security, the Trump campaign has taken a more extreme stance. Former President Donald Trump has spent months on the campaign trail pushing for mass deportations, proposing to deport an unprecedented 22 million people. This would severely impact migrant communities and the U.S. economy. Rhetoric aside, however, such an effort is condemned to fail from the start because of — ironically — one deeply rooted American value: family.

I am a researcher who has spent the last decade studying the movement of migrants through Mexico toward the United States. In this time, I have had the opportunity to meet hundreds of Central Americans moving northward toward the U.S. Some of the migrants I met had already lived in the U.S., been deported or chosen to leave, and were headed back again (sometimes for the second, third and fourth times).

These migrants had suffered countless terrible experiences. They’d spent time lost in the Arizona desert, nearly drowned in the Rio Grande, been kidnapped by drug cartels in Mexico, suffered hunger, faced deadly violence and walked thousands of miles. Despite all these dangers lying between them and the United States, they were headed back again (and again) for one primary reason: to get back to the families they had left behind.

For example, in 2015, I interviewed a man from El Salvador. At that time, he had been out of the United States for nearly a year, and had been deported three times from Mexico and once from the U.S. border when trying to enter California. When I asked him why he kept trying to get to the U.S., he explained: “I have a wife and three young daughters waiting for me in the United States.” He had lived in the U.S. for years, but after being stopped for speeding, he was deported to El Salvador. Ever since, he had been attempting to return.

When I asked if he feared the increased border policing, he said, "I'm not afraid. My life is there. I'm like Speedy Gonzales — small, fast and always escaping. No matter how much they try, I'll get away because my family is there." For the many migrants like him, there is no other option but to keep trying.

This strength and resilience of families — their desire to be together, to live their lives —are sufficient to thwart Trump's plans to deport 22 million undocumented migrants because, simply put, deported migrants will find a way to make it back. Of course, a combination of massive deportations at the border and from the interior of the United States would wreak havoc on family structures, the economy, and the nation’s social fabric. Still, families and communities would organize, move resources and mobilize to bring back the people they love, just as they always have.

Yes, for many Americans, immigration is a top concern in this election cycle. And deportation is the easy answer that, on the surface, looks like the obvious solution. But if we want order and control at the border, attacking families simply won’t work. The idea of mass deportation is not new — America has tried it since passage of the 1965 Immigration Act, and studies show it has never worked.

Instead, we must push politicians for more creative solutions that take into account and learn from our previous mistakes. Instead of thinking immigration as an issue of deportation, we have to think about it through the axis of inclusion, and recognition.

While calls for mass deportation are sure to fail, a more balanced approach to dealing with undocumented immigration would offer new pathways to legalization for undocumented immigrants (such as the parents of U.S. citizens) and open additional pathways for circular migration, where migrants could benefit from working in the U.S. for a period without having to permanently relocate to the United States. Such a solution might work.

What will not work is the mass deportation of parents, siblings, spouses, children, friends, neighbors and community members, who are destined to return to the U.S. through pure resilience (and to suffer greatly in doing so). And while Trump’s policies have constantly sought to dehumanize immigrants, in fact, his proposed deportation will fail because family ties and the desire to be with loved ones, despite dangers, are aspects of humanity at its best.

____

Garcia is an assistant professor of sociology at Yale University, specializing in international migration from Latin America. He is a public voices fellow with The OpEd Project.

____

©2024 The Fulcrum. Visit at thefulcrum.us. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments