Trump's plans to deport millions would have impact beyond the undocumented

Published in Political News

ORLANDO, Fla. — Former President Donald Trump’s threat of “mass deportation” of millions of people is a key vow of his re-election campaign and one that resonates with his supporters.

But the consequences of such a roundup would be sweeping in Florida and elsewhere: Sprawling holding camps for those awaiting deportation. Struggles for the state’s agricultural and hospitality industries. Legal residents, caught up in the search for illegal immigrants, required to regularly prove they belong here.

“This will create havoc in our community,” said Felipe Sousa-Lazaballet, who leads the Hope CommUnity Center in Apopka, which for decades as worked with immigrants in Orange County. “You would not only impact undocumented people. Our entire Central Florida community will be deeply impacted. Folks are afraid.”

Trump spokeswoman Karoline Leavitt said a large-scale “deportation operation” is necessary to stem “an unprecedented immigration, humanitarian, and national security crisis on our southern border.”

Neither Trump nor his campaign have provided a detailed plan for how that would be accomplished. But the former president has said he would have “no problem” using the military in the effort. And Tom Homan, head of Immigration and Border Enforcement during the Trump administration, told 60 Minutes this month there is a way to carry out mass deportation without separating families: “Families can be deported together.”

That speech chills the more than 700,000 U.S. citizens in Florida who have an undocumented family member, said Sousa-Lazaballet, who immigrated from Brazil at 14.

“I’m a U.S. citizen now, but I was undocumented for 15 years of my life, and I have family members who are undocumented,” he said. “He’s saying he’s going to use the military and essentially knock at everyone’s doors. Imagine what that would be like in terms of racial profiling.”

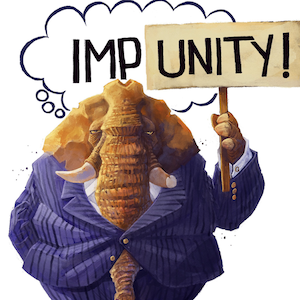

At the Republican National Convention in July, delegates waved signs reading “Mass Deportation Now.”

An American Values Survey poll this summer found that 79% of Republicans and 47% of independents supported “rounding up undocumented immigrants and putting them into militarized camps.”

The push for deportation from Trump and many other Republicans stems from their view that those who arrive without documentation have an unfair advantage over those who go through the full immigration process, contribute to “chaos” at the U.S.-Mexican border and impact the availability of jobs and housing for citizens across the country.

The number of undocumented in the U.S. is estimated at around 11 million, with more than 1 million in Florida.

The state’s agriculture, construction and hospitality industries rely on undocumented workers, who account for about 10% of their work force, according to the Florida Policy Institute.

Elizabeth Aranda, director of the Immigrant Well-Being Research Center at the University of South Florida, said history has shown the problems with deportation sweeps. In the notorious roundup of Mexicans in the 1950s, dubbed “Operation Wetback,” she said, U.S. citizens were caught up and deported when they couldn’t prove their identity.

The same could happen now, with the burden of proof on the immigrants themselves, Aranda said, if they were not afforded the right to a lawyer in immigration court.

“It would be such an abusive situation,” she said. “And yes, all of us would become the immigration police. … I think it would be a turn for our society that we don’t want to take.”

Trump’s plan would “use the force of the federal government” to push states and local authorities to round up anyone suspected of being in the United States without permission, said Ediberto Roman, the director of Immigration and Citizenship Initiatives at Florida International University.

Roman said that he would advise any Hispanic to carry proof of citizenship or legal residency at all times.

“If you happen to be driving or walking or existing while brown, you’re going to be presumptively challenged in terms of the appropriateness of you being here,” Roman said. “It’s going to be, frankly, a reign of terror.”

Who has legal status in the U.S. could also easily change.

The former president has also called for an end to universal birthright citizenship, in which the 14th Amendment grants citizenship to anyone born in this country, and had tried to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which protects 53,000 “Dreamers” brought into the country without permission as children.

Refugees, non-citizens with temporary approval to be in the U.S., might feel the impact of a second Trump presidency most quickly.

There are nearly 500,000 Haitians in Florida, and thousands of them are in the U.S. under Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, renewed by the Biden administration until early 2026. The program allows migrants from unsafe countries to live and work legally in the U.S.

Trump has said he would revoke Haitians’ legal status, calling them “illegal immigrants as far as I’m concerned.”

Last month, Trump and JD Vance, his vice presidential candidate, mocked legal Haitian residents in Ohio, falsely accusing them of eating dogs and cats even as local Republicans and business owners defended them.

Lugard Brevil, 32, a Haitian native, walked the length of the Americas from Chile to the U.S. before he was granted asylum and found a job working in the Orlando hospitality industry. The earthquake in Haiti in 2010 destroyed his home, and his family has died, so now “this is his home,” said Nattacha Wyllie, executive director of the Orlando-based Haitian American Art Network, who translated for Brevil.

“He has not been in trouble,” she said. “He goes to work and he does what he has to do.”

Nearly half of the hospitality industry workers in Central Florida are Haitian, she said. Without them, “There would be no Disney, ” she added. “There would not be hotels for these tourists to come through.”

Besides Haitians, thousands of Venezuelans and Cubans protected by TPS could be in danger of losing their status, said North Miami Vice Mayor Mary Estime-Irvin, the chair of the Orlando-based National Haitian American Elected Officials Network.

“They are legally here,” she said. “This country was based on the very fabric of immigrants of all countries. Why are we picking on Haitians? Why are we picking on any groups?”

____

©2024 Orlando Sentinel. Visit at orlandosentinel.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments