Misspoke: The long and winding road to becoming a political weasel word

Published in Political News

During the Sept. 24, 2024, debate, Democratic vice presidential hopeful Tim Walz said he “misspoke” when asked to clarify his story of being in Hong Kong during the Tiananmen Square crackdown in June 1989.

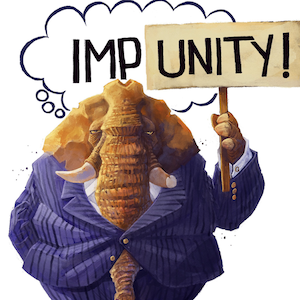

To many, Walz’s use of the word misspoke came across as an attempt to weasel out of what was at best an embellishment and at worst an outright lie.

The word misspoke has certainly long been used to politically backpedal after verbal inaccuracies or blunders, as Ronald Reagan learned in 1981 after he said that Syrian surface-to-air missiles placed in Lebanon were “offensive weapons,” when they were in fact defensive weapons. Both Presidents Bill Clinton and the much “misunderestimated” George W. Bush likewise were deemed to have misspoken after making mistakes, big and small.

For instance, a spokesperson for Clinton claimed he had misspoken when the then-president said that North Korea would not be allowed to develop a nuclear bomb – after there was reason to believe they had already developed them. During George W. Bush’s term in office, verbal errors were so common they earned a nickname of their own: “Bushisms.”

But misspoke’s extension to factual fabrication is one step further down the semantic road. In using it in this way, Walz joined other “misspoken” politicians, such as Hillary Clinton, who used it after falsely recollecting having landed in Bosnia under sniper fire.

As a sociolinguist who writes about how language changes over time, misspoke’s euphemistic recasting of lying as an inadvertent mistake calls for deeper linguistic scrutiny.

To understand how and why words morph like this, linguists like to trace them to their very beginnings.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “misspeaking” is quite old in the history of English, appearing as “missprecon” in a Northumbrian text dating before the 11th century. Its original sense was one of “to grumble” or “to mumble,” a meaning now obsolete.

But after the 11th century, its meaning shifted from inarticulateness to that of speaking amiss or disparagingly, often mentioned in reference to saying something improper or upsetting. Chaucer makes use of this sense in the “Miller’s Tale”: “And therfore if that I mysspeke or seye, Wyte it the ale of Southwerk, I you preye,” where the Miller handily blames a bit too much ale for whatever impropriety might fall from his mouth.

Around the time Chaucer was composing “The Canterbury Tales” in the late 14th century, the word “misspeak” branched off down yet another semantic path, taking on the meaning of “to speak incorrectly or misleadingly.” It is this sense that gave birth to the modern political mea culpa used when backtracking on a misleading prior statement, such as by Sen. John McCain after he claimed President Barack Obama was directly responsible for terrorist attacks on Americans.

These shifts in the meaning of a word over time fall under what linguists refer to as “semantic broadening.” Semantic broadening, which means expansion of a word’s meaning, is incredibly common, generally occurring when a word becomes used more frequently and across more situations. As a result, its core sense can expand to take on supplemental or tangential meanings.

Semantic shift like this is constantly at work, pushing and pulling senses in related but new directions to stay relevant to the needs of speakers.

The word “soon,” for instance, at first carried a meaning of “immediately,” but human nature being what it is, its meaning began to creep in the direction of “as immediately as possible” as people took their merry time.

Some new meanings, such as the nonliteral use of “literally” and Walz’s use of “misspeak,” are sites of contest, with multiple meanings at play.

The semantic broadening of misspeaking to cover not just misleading but knowingly false information didn’t start with Walz, nor did it begin with Clinton. In fact, this politically expedient expansion seems to go back at least to the Nixon administration.

In 1973, Nixon and his advisers were called to task in a Time article accusing them of a tendency to “make flat statements one day, and the next day reverse field with the simple phrase, ‘I misspoke myself.’” Given the Watergate scandal, it’s safe to say that misspoke as used by his administration had already shifted into deceptive speech territory.

Perhaps misspeaking’s semantic slippery slope started even further back, when the prefix “mis,” with its sense of “badly,” combined with “speaking.”

Consider other potentially weaselly words that are also formed by “mis” prefixation: misunderstood, misinterpret, mishear, mistake. These are all examples of words, like misspeak, that can and have been used by politicians to avoid taking responsibility for the false or “misleading” things they say.

Even if led astray by its prefix, from a linguistic perspective, the broadening of misspeak to cover not just incorrect but fabricated statements turns out to be not such a surprising development given the tendency of words to take on new senses over time, particularly in the world of political doublespeak.

The bigger surprise might be how this new meaning translates with voters, but that’s one surprise that will have to wait for the ballot box.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Valerie M. Fridland, University of Nevada, Reno

Read more:

Presidential pauses? What those ‘ums’ and ‘uhs’ really tell us about candidates for the White House

Why George Santos’ lies are even worse than the usual political lies – a moral philosopher explains

From ‘dada’ to Darth Vader – why the way we name fathers reminds us we spring from the same well

Valerie M. Fridland does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments