Latino voters are a growing force in Pennsylvania’s old industrial towns − and they could provide Harris or Trump with their margin of victory

Published in Political News

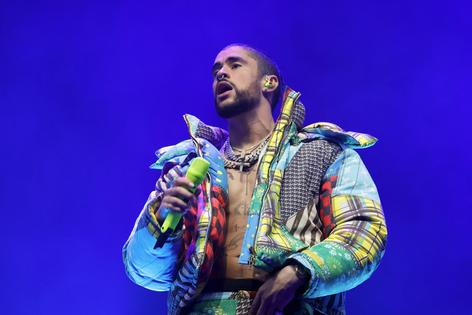

After Taylor Swift endorsed Kamala Harris for president in early September 2024, posting a message to her 284 million fans on Instagram, some Democratic strategists suggested that an endorsement from Puerto Rican recording artist Bad Bunny could do more to sway the election – particularly in the key swing state of Pennsylvania, which is home to about 300,000 eligible Puerto Rican voters.

But when many Americans think of Pennsylvania’s deindustrialized eastern counties – including presidential bellwethers such as Northampton – they may think more of Billy Joel’s “Allentown” than Bad Bunny’s “Una Velita,” a song about the aftermath of Hurricane Maria.

As a professor of history and director of Latina/o Studies at Penn State, I think that both entertainers – the legendary singer-songwriter and the Grammy-winning titan of reggaeton and trap – can help explain the political terrain in the Keystone State, which is widely viewed as the battleground that will determine the next president.

In 1982, when Billy Joel recorded his somber song about workers left behind because “they’re closing all the factories down,” he was mainly describing the situation in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 6 miles from Allentown.

Beginning in the late 1970s, the massive Bethlehem Steel Corp. began to lay off tens of thousands of workers. But Joel found that not much rhymed with “Bethlehem,” so he used the neighboring city instead.

By the 1970s, Pennsylvania’s smaller industrial cities such as Bethlehem, Hazleton, York, Reading and Lancaster were losing population and vitality, and in many cases had been declining for decades.

And for many Americans, especially those outside Pennsylvania, the image of these cities hasn’t changed since. They still think of shrinking cities populated by white factory workers.

But Allentown, Bethlehem and other older industrial cities in Pennsylvania have made a remarkable recovery thanks in part to the arrival of new residents – most of them Latinos from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. Since the 1990s, these newcomers have helped restore population growth, stabilize housing markets and provide labor to new industries such as warehousing and transportation.

Allentown is now 54% Latino – a higher Latino percentage than Los Angeles.

Lancaster and York, which are 40% and 38% Latino, respectively, have significantly larger proportions of Latinos than Chicago and New York. And Reading, with 69% Latinos, is almost as Latino as Miami, at 70%. Of course, the overall number of Latino voters in those major cities is much larger.

Three factors are driving Latinos to settle in these cities. They tend to have plenty of warehousing and logistics jobs, affordable housing and a small community feel – particularly in comparison to New York City, where many of these new residents came from rather than directly from Puerto Rico or the Dominican Republic.

Industrial cities such as Allentown, Bethlehem and Reading had long been Democratic strongholds because of the labor movement. And they still are – though that’s now a result of both union influence and the political leanings of Hispanic voters.

According to a 2022 survey from Pew Research Center, 60% of Latino adults in the U.S. say the Democratic Party represents the interests of “people like them,” compared with 34% who say the same of the Republican Party.

The 2020 U.S. census found for the first time that there were more than 1 million Latinos in Pennsylvania – a figure that has since increased to more than 1.1 million. This includes about 580,000 eligible voters, though Latinos tend to both register and to vote at much lower rates than non-Latino white and Black voters.

It’s certainly an oversimplification to attribute a state or national margin of victory to just one demographic – whether soccer moms in the 1990s, office-park dads and values voters in the 2000s or Latinos in 2024.

But in a very close election like this one, small shifts in the margins among key groups, such as Latino voters in Pennsylvania, can determine who becomes president.

The Latino vote encompasses various nationalities and identities, and partisan preferences differ markedly among them.

For example, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans have shown the greatest loyalty to the Democratic Party, while Cubans are famously the most Republican-leaning, followed by Venezuelans.

Moreover, Pennsylvania’s Hispanic population shows a very different distribution from the national scene. Across the U.S., people of Mexican ancestry account for about 60% of all Latinos, Puerto Ricans compose 9.5%, and Cubans, Dominicans and Salvadorans make up about 4% each.

But in Pennsylvania, 53% of Latinos are Puerto Rican and 13% identify as Mexican. Meanwhile, 11% say they are Dominican, and only 3% Cuban.

And this brings us back to Bad Bunny, who was born and raised in Vega Baja, a small city on the northern coast of Puerto Rico. People born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens, but can vote in U.S. elections only when they live on the mainland. And those who live in Pennsylvania could prove pivotal come November.

Overall, Latinos were part of the coalition that in 2020 helped Joe Biden win the state of his birth and go to the White House.

Biden won about 75% of Pennsylvania Latino votes to 25% for Trump. Given that Biden won Pennsylvania by just 80,000 votes in 2020, how the state’s 580,000 Latino voters split their votes in 2024 could determine the next president.

This is borne out in the most recent polling of Latinos in bellwether Northampton County. Among Latinos in the county, the September 2024 poll found that Harris was leading Trump 60% to 25%.

This was certainly a strong Harris lead, but the significance was in the margins.

The poll found that Harris had not reached Biden’s Latino vote share statewide in 2020, and Trump was also falling short of his own 2020 Latino totals. So by the numbers, about 90,000 Latino voters might still be undecided – and therefore could be pivotal in their decisions on whom to support and by what margin.

It is for this reason that there has been so much talk about whether Bad Bunny will make an endorsement in the race. Both campaigns clearly believe that the support of high-profile Latinas and Latinos might help persuade members of the community.

In addition to national support from stars such as America Ferrera and Rosario Dawson, the Harris campaign recently held a rally in Allentown featuring Emmy-winning actress Liza Colón-Zayas from “The Bear,” and “Hamilton” and “In the Heights” star Anthony Ramos – both of Puerto Rican descent.

The Trump campaign, meanwhile, brought Puerto Rican rappers Anuel AA and Justin Quiles on stage to endorse the former president at his Johnstown rally in late August.

Latinos are like any other voters in that they make their decisions based on some combination of economic interests, cultural values and community sentiment. Nobody knows whether a celebrity endorsement will make a difference – but campaigns will try anything to get undecided voters to relate to their candidate.

The Democratic National Committee announced on Sept. 29 it would be spending more money in the final weeks leading up to Election Day on engaging Puerto Rican and other Latino voters in Pennsylvania.

So while the biggest concentrations of Hispanic voters in the U.S. are still in the Southwest, the most decisive group of Latina and Latino voters may be those living far from the border, in eastern Pennsylvania.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: A. K. Sandoval-Strausz, Penn State

Read more:

Pennsylvania continues tradition as ‘keystone state’ in presidential elections

What early 2024 polls are revealing about voters of color and the GOP − and it’s not all about Donald Trump

So-called ‘Latino vote’ is 32 million Americans with diverse political opinions and national origins

A. K. Sandoval-Strausz has received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Comments