Kamala Harris is no Hubert Humphrey − how the presumed 2024 Democratic presidential nominee isn’t like the 1968 party candidate

Published in Political News

Staring straight at the camera, with a grave expression on his face, the president uttered these famous words: “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.”

Lyndon Johnson made that announcement at the end of his nationally televised address on the Vietnam War on March 31, 1968. Those words now echo loudly, as pundits recall them in the wake of Joe Biden’s withdrawal from the 2024 presidential election.

Like Biden, Johnson was a sitting Democratic president who was eligible for another term. Both men understood the odds against reelection, and both opted out. Their decisions shape their legacies as presidents who compiled impressive records yet failed to sustain their power across a longer span.

As the author of “The Men and the Moment,” a short narrative history of the presidential election of 1968, I have reflected on these parallels, too. But I think we can learn more from the differences in the circumstances of Biden’s and Johnson’s withdrawals. They illustrate the high hurdles that the presumed Democratic presidential nominee, Vice President Kamala Harris, now must clear, while also sounding a note of hope for the Democratic Party.

One important distinction between Johnson and Biden was the nature and timing of their decisions.

Johnson arrived at his decision not to run for a second full term on his own, five months before the Democratic National Convention. It surprised everyone. No one expected this larger-than-life president – the force behind a massive slate of liberal government programs known as the Great Society, as well as the escalation of the Vietnam War – to voluntarily give up power.

But Johnson suffered as communist forces launched the Tet Offensive against U.S. troops in Vietnam. At home, critics on both the right and left blasted him. He realized that he could no longer forge a consensus in Congress. He rationalized that he could serve his final year in office by crafting peace in Vietnam.

That choice allowed other candidates to compete for delegates, from his loyal vice president, Hubert Humphrey, to anti-war senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy.

Biden, by contrast, renounced his nomination well after the primaries and just one month before the convention. Moreover, he succumbed to external pressure from donors and party leaders to leave the race, stemming from his disastrous performance in the June 27, 2024, debate.

Biden’s prolonged candidacy appears to have dictated that the party anoint Harris as his successor. Can she craft a message that resonates with voters? Can she win their trust and respect?

Running in the primaries would have provided answers. Instead, for now, those questions linger.

Another divergence between 1968 and 2024 was the process of delegate selection.

In 1968, only a handful of states had binding primaries, where all delegates pledged their vote to the election’s winner. It was more common for party insiders to choose delegates through state conventions and other bureaucratic means.

Humphrey campaigned through the spring and summer of 1968, but he avoided primary elections. McCarthy and Kennedy battled in those primaries, each trying to claim the mantle of the popular anti-war challenger. Then Kennedy was assassinated in June, and McCarthy failed to rally a viable coalition. Humphrey captured the nomination by winning the support of most Democratic officials.

By the next election cycle, the party had enacted reforms for choosing delegates, including open primaries and caucuses. That system remains in place now.

Yet this year’s extraordinary turn of events means that Harris has bypassed that system. Unlike Humphrey, she has to overcome voters’ doubts about whether she is the genuine preferred candidate of the Democratic Party.

If these distinctions from 1968 illustrate the obstacles before Harris, a final difference suggests one of her greatest assets: She has the support of almost the entire Democratic Party, including the sitting president.

Humphrey could not say the same. His own president kept hanging him out to dry.

To attract voters seeking change, Humphrey needed to articulate his own position on the Vietnam War, but Johnson was unwilling to make concessions as a prelude to peace. He bullied Humphrey into supporting his tough stance, which included a reluctance to halt bombings in North Vietnam.

Johnson didn’t respect Humphrey. Early in the race, LBJ privately beseeched Republican Nelson Rockefeller to run. By the general election, Johnson seemed more politically aligned with Republican nominee Richard Nixon than with his own vice president.

Vietnam was cleaving the party, and Humphrey could not heal the wounds. Finally, at the very end of September, Humphrey cast his independent stance on the war, pledging to halt the bombing of North Vietnam “as an acceptable risk for peace.” But it was too little, too late.

McCarthy, his fellow Minnesotan, offered the limpest of endorsements, and not until one week before Election Day. In the end, Humphrey could not unite Democratic voters, and Nixon triumphed.

Now, for all the ideological differences among prominent Democrats, the party looks unified in its ambition to negate the threat they see in Donald Trump. Biden will almost certainly exhibit more political generosity than Johnson.

In addressing the monumental task of a late presidential run against the polarizing figure of Trump, Harris faces challenges that are unique in American political history. If she can overcome them, she might avoid the fate of Humphrey.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

Read more:

Until 1968, presidential candidates were picked by party conventions – a process revived by Biden’s withdrawal from race

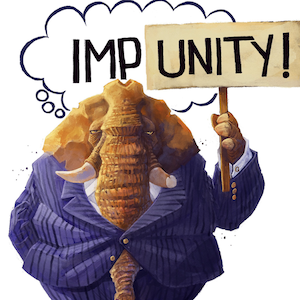

GOP attacks against Kamala Harris were already bad – they are about to get worse

Aram Goudsouzian does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments