Can a brush with death change politicians? It did for notorious Alabama segregationist George Wallace

Published in Political News

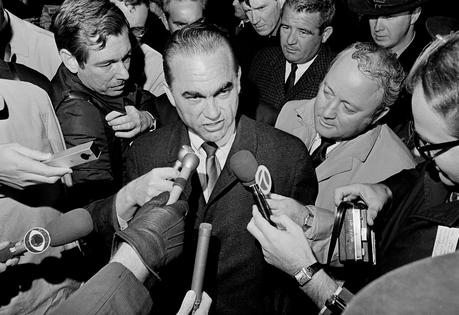

Donald Trump’s narrow escape from an assassin’s bullet led me – a historian who has written about political polarization and the Civil Rights Movement – to think back to another norm-smashing populist who encountered death on the campaign trail: former Alabama governor and U.S. presidential candidate George Wallace.

By 1972, Wallace’s image was fixed in most Americans’ minds as the face of the white South’s violent response to the Civil Rights Movement. Wallace had skillfully deployed divisive, racially tinged attacks against liberals, government and protesters to become a serious contender for the presidency.

So, Wallace turned heads when he publicly apologized and pleaded for forgiveness for his segregationist past after a 1972 assassination attempt at a campaign rally in Maryland left him paralyzed.

It’s impossible to look into Wallace’s heart and understand what moved him. Yet three factors probably loomed large.

First, the brush with death. It upended Wallace’s life and forced him to end his 1972 bid for the presidency. It also left a pugnacious man who had been a boxer in his youth and was proud of his physical prowess bound to a wheelchair. He underwent frequent surgeries and lived in constant pain.

It’s common for those who have faced death to reflect on their mortality and their life. Wallace was no exception.

Religion also may have played a role. While he was an earthy, profane man who didn’t resist temptations of the flesh, Wallace couldn’t escape the religious views that he had imbibed as a child and that permeated Southern culture. Faced with his own mortality, he thought about the fate of his soul and sought redemption by accepting Jesus, repenting and seeking forgiveness.

Less than a month after Wallace was shot, civil rights icon Shirley Chisholm visited him in his Maryland hospital room.

“I wouldn’t want what happened to you to happen to anyone,” she told the governor.

Wallace’s daughter Peggy recalled that Chisholm’s words brought her father to tears and he “started to change.”

In 1974, Wallace professed his conversion in a speech at Jerry Falwell’s Lynchburg, Virginia, megachurch. He told the congregation he had “been through the valley of the shadow of death,” and proclaimed, “I am whole through the grace of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.”

Wallace reached out to those he had wronged, including John Lewis, the civil rights leader whose skull had been broken by Wallace’s state troopers in Selma in 1965. Lewis was moved by their 1979 encounter.

“During that meeting, I could tell that he was a changed man; he was engaged in a campaign to seek forgiveness from the same African-Americans he had oppressed,” Lewis wrote for The New York Times in 1998. “He acknowledged his bigotry and assumed responsibility for the harm he had caused. He wanted to be forgiven.”

Politics had been Wallace’s life since he first won election to the Alabama Legislature in 1946. He could barely breathe without it, even after being nearly killed on the campaign trail.

“I don’t believe he needs a family,” his second wife, Cornelia, commented in the midst of an acrimonious divorce in 1978. “He just needs an audience.”

Wallace’s segregationist persona was a product, apparently, of politics. As a college student and budding politician, he was progressive by Southern standards: He avoided race-baiting and called for greater support for public services that benefited working-class Alabamians.

Years later, Ruth Johnson, whose husband, Frank, became a champion of civil rights as a federal judge, remembered Wallace as a college friend. “We were young and idealistic,” Ruth recalled. “And we loved George for his enthusiasms.”

In the late 1940s and 1950s, Wallace eschewed extremism. He refused to join the Dixiecrat rebellion against the Democratic Party’s civil rights platform at the 1948 Democratic convention. And he had a reputation for dealing fairly with Black attorneys and plaintiffs during his years as a state judge.

That changed after he lost the Democratic nomination for governor in 1958 to a rival who courted the Ku Klux Klan and openly appealed to white racism. With the South in flames as the Civil Rights Movement accelerated, Wallace won election in 1962 as a full-throated segregationist.

“Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” he proclaimed in his 1963 inaugural address. Wallace physically confronted a U.S. deputy attorney general and federal marshals as they attempted to enforce a court order admitting a Black woman to the University of Alabama.

Ambitious and sensing that racism wasn’t limited to the South, Wallace entered three Democratic presidential primaries in 1964 during his first term as governor. Then, after leaving office in 1967, he launched an unsuccessful third-party bid for the presidency in 1968.

He was reelected governor in 1970 and then pursued the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972 until his near-assassination. Despite his injuries, he remained in office, winning election to a third term and serving until 1979.

In 1983, even as Wallace’s physical and mental condition deteriorated, he won a fourth term as governor. Being in the limelight was “a matter of life and death” for him, a long-term adviser observed.

The South had changed as a result of the movement Wallace fought so viciously, and Black people had become a major force in the Democratic Party. Ever the politician, Wallace changed too, appointing Black politicians to positions at all levels of his administration.

Wallace wasn’t a saint. Two marriages ended in divorce, in part because of his emotional abuse of his wives.

Spike Lee’s documentary “4 Little Girls,” which recounts white supremacists’ 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four Black children, features chilling interviews with Wallace. They reveal a man who treated Black people who worked for him in the 1980s in an embarrassingly patronizing manner.

Still, Wallace reflected, repented and asked forgiveness. That’s worth remembering at a time when many of us hope our leaders will become introspective and perhaps even change.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Donald Nieman, Binghamton University, State University of New York

Read more:

Lincoln called for divided Americans to heed their ‘better angels,’ and politicians have invoked him ever since in crises − but for Abe, it was more than words

What 1860 and 1968 can teach America about the 2020 presidential election

Exploring the complexities of forgiveness

Donald Nieman receives funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the American Council of Learned Societies. In 2024 he has made donations totaling $460 to the following organizations: the Democratic National Committee, Sen. Jackie Rosen, the Democratic Election Fund, Democratic Majority, Democrats 2024 and Progressive Takeover..

Comments