How the Gaza humanitarian aid pier traces its origins to discarded cigar boxes before World War II

Published in Political News

Palestinians in Gaza have begun receiving humanitarian aid delivered through a newly completed floating pier off the coast of the besieged territory. Built by the U.S. military and operated in coordination with the United Nations, aid groups and other nations’ militaries, the pier can trace its origins back to a mid-20th century U.S. Navy officer who collected discarded cigar boxes to experiment with a new idea.

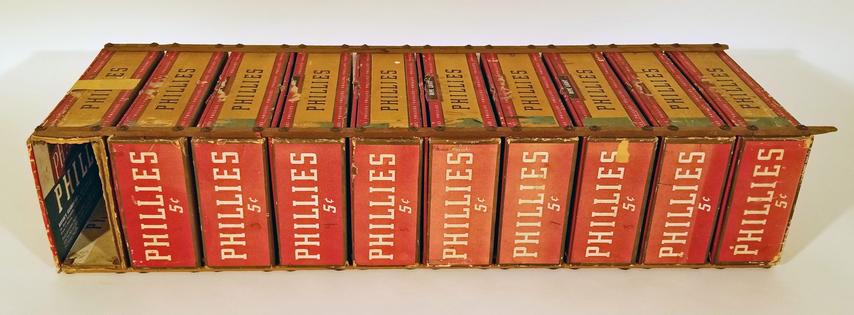

Among the artifacts of the military collections of the National Museum of American History, I happened upon these humble cigar boxes and the remarkable story they contain.

In 1939, John Noble Laycock, then a commander in the Navy’s Civil Engineer Corps, was assigned, as the war plans officer for the Navy’s Bureau of Yards and Docks in Washington, D.C., to help prepare for a potential war in the Pacific.

Laycock had to figure out how to construct naval bases on undeveloped islands. The top priority would be what the military called “naval lighterage,” the process of getting cargo and supplies from ships to a shoreline where there were no ports or even piers to dock at.

That’s exactly the problem the relief effort faced in Gaza – and one that military forces and humanitarian groups have faced countless times in the past century.

In the office files of his predecessors, Laycock found plans developed in the 1930s to use small pontoons – essentially floating boxes – that could be easily transported and quickly assembled by hand into larger barges or floating platforms. But Laycock saw problems with the plans’ design and method of connecting the pontoons to each other. And he had an idea.

In my research into his work, I found that around July 1940, Laycock began visiting every concessionaire in the Navy’s headquarters building, which was then located along the National Mall, asking them to save empty cigar boxes for him. Laycock and a helper lined up the boxes and spaced them evenly. Then they linked them together using wooden strips from children’s kites, which they fastened to the corners of the boxes with small nuts and screws.

The simple model demonstrated that it was possible to connect individual, uniformly sized, small pontoon boxes into a much longer, and much stronger, floating beam. Multiple beams could be combined into the base for a platform of any needed size. A big enough platform could support cargo, military trucks and armored vehicles weighing up to 55 tons.

In August 1940, during his family vacation, Laycock figured out how exactly to connect the individual pontoons, which were made of steel and not wood or cardboard like his cigar-box model. He designed steel fasteners – scaled-up nuts and bolts nicknamed “jewelry” that could be inserted and tightened by hand – that could handle the stress of the movement of the ocean beneath a floating platform.

Through trial and error, and applying various military requirements such as the width of the steel plates, weight of the empty pontoon, depth needed to float and load-bearing capacity, Laycock designed a basic pontoon 5 feet high by 7 feet long by 5 feet wide. He also designed a curved section to serve as the bow of a pontoon-based transport vessel. By 1941, testing had proved the design and the system were ready for mass production.

The pontoon technology first went to war in the South Pacific in February 1942 with the Naval Construction Force, nicknamed the Seabees, who took it to Bora Bora in the Society Islands. The Seabees were pleased with how it worked and helped contribute to the system’s nickname – Laycock’s “magic box.”

The universal nature of the pontoons permitted construction of an array of floating structures, including dredges, barges, floating cranes, workshops, storehouses and gas stations, tug boats, pile drivers and dry docks. These pontoon structures could be found from Guadalcanal to the Marianas, the Aleutians and the Philippines.

The planning for the invasion of Sicily in July 1943 found another use for Laycock’s pontoon system. In late 1942, Royal Navy Capt. Thomas A. Hussey recognized that the Sicilian beaches had gentle slopes. During an invasion, landing craft, especially those designed for tanks, could be expected to run aground several hundred feet from dry land, in water 6 feet deep. Even waterproofed vehicles would be swamped and could sink.

Aware of Laycock’s pontoons, Hussey inquired whether the units could form a floating road, called a causeway, to bridge the gap between ship and shore. Laycock designed a method to build narrow causeways two pontoons wide and 30 pontoons long – roughly 175 feet. Setting them side by side would form a 325-foot floating causeway. They could even be towed or carried by landing craft and deployed upon arrival in shallow water.

Tested successfully in mid-March 1943, the causeways proved a success at Sicily. In 23 days of round-the-clock shifts, the Seabees unloaded over 10,000 vehicles, including trucks, jeeps, half-tracks and towed artillery, on the causeways. Senior American and British leaders said the landings could not have succeeded so rapidly were it not for the pontoon causeways.

Much like Sicily, the Normandy coast of France also featured beaches with gentle, flat slopes. Floating pontoon causeways were key to the June 6, 1944, D-Day landings for U.S., British and Canadian forces. Engineers would anchor one end of the causeway on the shore and extend the structure out into the ocean far enough that whether it was low or high tide, cargo-carrying vessels could dock without running aground.

Along the sides, every few hundred feet along the causeway, additional pontoons were attached to form piers, so multiple vessels could dock at the same time, regardless of tidal conditions. They could unload directly onto dry pontoons just as they would at any regular pier or dock.

This system allowed a massive, around-the-clock flow of tanks, trucks, artillery, supplies and personnel to support the fighting as the Allied forces moved inland through Normandy over the coming months.

Over the decades, this concept, with technological advancements in construction and fasteners, evolved into pontoon systems used in the Korean and Vietnam wars. Those have since been improved as well and have helped provide humanitarian aid such as in Haiti after a massive earthquake in 2010.

The pier at Gaza involves both parts of the pontoon system – Laycock’s original floating platform as a cargo transfer site 3 miles offshore, and the British-suggested floating causeway and pier system allowing truck deliveries to get to dry land. All from a humble concept model of cigar boxes.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

Read more:

I’ve spent decades overseeing relief operations around the world, and here’s what’s going wrong in Gaza

Delivering aid during war is tricky − here’s what to know about what Gaza relief operations may face

Frank A. Blazich Jr. does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments