Lisa Jarvis: Trump leaving WHO puts US at the back of the line in global health

Published in Op Eds

President Donald Trump’s swift move to withdraw the U.S. from the World Health Organization will compromise global health — and is no way to Make America Healthy Again.

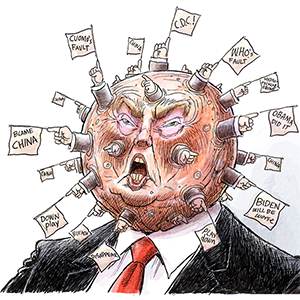

Trump is picking up a task he started back in 2020, when he first tried to pull out of the WHO. At the time, he claimed the organization helped China cover up the extent and source of COVID. That effort got a reprieve from former President Joe Biden, who reversed the decision on his first day in office.

Trump’s new executive order revives his previous criticisms and complaints that the U.S. is paying more than its fair share toward keeping the global health effort afloat. “World Health ripped us off,” he told reporters while signing executive orders on Monday.

It’s true that the U.S. contributes more money than any other country toward advancing the WHO’s mission of improving global health. In 2022 and 2023, we kicked in $1.28 billion, $400 million more than the second-highest contributor, Germany. But weigh that cost against the dangerously high price of withdrawing and it looks like a pretty good deal.

It’s impossible to overstate the WHO’s vital job of ensuring public health for billions of people. The organization steps in amid health emergencies (whether due to a natural disaster or war); acts as the world’s pathogen police, constantly surveilling existing and emerging threats; and drives development of vaccines and medicines. And, of course, it coordinates the response amid global pandemics.

Withdrawing from the WHO runs counter to our national interest, says Lawrence Gostin, director of Georgetown University’s O’Neill Institute for National & Global Health Law. “When all major decisions are undertaken around the world on health — like the pandemic treaty, the next director general, or when we have to respond to a major health emergency — the U.S. will be on the outside looking in.”

What does it mean to be on the outside looking in? The U.S. might not get the most up-to-date information on disease outbreaks and will lose its position as the most influential voice in shaping global health policies. That will affect the health of people around the world — including in the U.S.

For example, the WHO coordinates a vast influenza network that for decades has tracked and coordinated a global response to seasonal and emerging flu viruses. That effort guides decision-making about the composition of our routine flu shots as well as helps researchers determine when and how to develop novel vaccines against potential pandemic-causing pathogens. The U.S. will lose its voice in those discussions as well as the earliest access to those data.

And when it comes time to put shots in arms in an emergency, the WHO is responsible for determining how those get distributed. “We used to be at the front of the line, expecting to get vaccines and life-saving treatments first,” Gostin says. “Now we’re going to be at the back of the line.”

The U.S. will also be ceding its outsize influence over global health issues. Although Trump centered his decision to withdraw on China, which he has falsely claimed owns and controls the WHO, the move could put more power in his adversary’s hands. For example, the WHO acts as a regulatory body for low- and middle-income countries that cannot afford their own health infrastructure, and the U.S. currently has a prominent seat at the table when it comes to guiding health priorities there.

Walking away from the WHO would elevate the influence of other countries like China and Russia, which could have very different, and sometimes problematic approaches to health, “and will be all too happy to control what happens,” says Chris Beyrer, director of the Duke Global Health Institute.

Meanwhile, global health will suffer. The WHO will need to fill the financial hole left by the U.S. — and if it doesn’t, critical programs will be lost. Because of the WHO’s gargantuan efforts alongside the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and several nonprofits, the world is on the cusp of eradicating polio.

“But that’s a reversible trend,” warns Colin Carlson, an epidemiologist at the Yale University School of Public Health. Although much has been made of softening vaccination rates in the U.S. (a valid concern), the larger threat is if uptake falters in countries where risks of preventable infections are high, whether due to lack of funding or coordination.

Then there’s the compounded effect of Trump’s withdrawal from WHO while also switching course on U.S. policy on climate change, which ups the risk of new and existing infectious diseases affecting Americans. A hotter world raises the risk of a spillover of pathogens from animals to humans and can push mosquitos carrying diseases like dengue and Zika into areas that previously didn’t worry about the viruses. “We are in an era where there is an increased number of cross-species transmissions and outbreaks, largely due to habitat destruction and climate change,” Beyrer says.

So many facets of global health hinge on everyone working together. Pathogens don’t know borders, and they certainly don’t recognize political parties. Pretending otherwise is a bad way to protect the health of Americans.

_____

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lisa Jarvis is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering biotech, health care and the pharmaceutical industry. Previously, she was executive editor of Chemical & Engineering News.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments