Politics

/ArcaMax

James Stavridis: 10 ways to force Putin back to the bargaining table

Vladimir Putin came to Alaska and got the red-carpet treatment, complete with a fighter-jet flyover and a warm presidential handshake. The state was an ironic location for a summit given Russia’s continuing seller’s remorse over having sold it to America in the mid-19th century. While expectations were low for a full ceasefire, most ...Read more

Mary McNamara: Let's unpack our toxic fixation with 'the TikToker who fell in love with her psychiatrist'

Let’s unpack our need to unpack the whole “woman on TikTok who fell in love with her psychiatrist” saga.

First the facts: Kendra Hilty recently posted 25 videos on TikTok in which she discussed her decision to end four years of 30-minute monthly sessions (most of them on Zoom) with a male psychiatrist who prescribed her medication. At ...Read more

Editorial: Bob Odenkirk's reflection on fatherhood hits home

When comedian Mike Birbiglia asked actor Bob Odenkirk whom he’s jealous of, the Chicago-area native gave an answer that left the podcast host speechless.

“Anyone who has little kids at home,” Odenkirk said.

“There’s no question,” he continued. “I knew what I was doing when I had kids growing up. I was being a dad. I mean, that ...Read more

Commentary: AI will be more disruptive than COVID. Which party can seize the moment?

Democrats, bless their hearts, keep trying to figure out the magic formula to stop President Donald Trump. But here’s a cold splash of reality: If Trump’s popularity ever collapses, it will probably be because of something completely beyond their control.

In 2020, it wasn’t some brilliant strategy that defeated Trump. It was COVID. A ...Read more

Commentary: 'Made in America' is alive, well and misunderstood

The president supports purchasing goods that are “made in America.” To encourage this, President Donald Trump has imposed tariffs on imports from literally every country that the U.S. does business with, with 10% to 15% as the floor baseline. His hope is that tariffs would push more companies to move their manufacturing and production ...Read more

Commentary: Medicaid is not a luxury, it's a lifeline

Every time I chased stability to build a future, chronic illness pulled me back into a hospital bed.

Sometimes it has been for days, sometimes weeks. My life with sickle cell disease is a relentless cycle of excruciating pain, nerve damage and blood transfusions. I’ve survived two kidney transplants, countless medical procedures and numerous ...Read more

Commentary: The cost of small lies -- A citizen's response

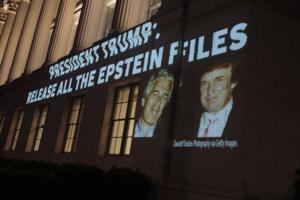

Over the past several years, we've watched President Donald Trump and his administration wield misinformation not just as a shield, but as a weapon—deploying conspiracy theories, half-truths, and outright falsehoods to bury tough headlines and duck accountability.

The first months of Republican control, instead of being a time of bold policy...Read more

Gustavo Arellano: Can homegrown teens replace immigrant farm labor? In 1965, the US tried

I sank into Randy Carter's comfy couch, excited to see the Hollywood veteran's magnum opus.

Around the first floor of his Glendale home were framed photos and posters of films the 77-year-old had worked on during his career. "Apocalypse Now." "The Godfather II." "The Conversation."

What we were about to watch was nowhere near the caliber of ...Read more

Commentary: You want to leave TikTok? Good luck

Trying to delete TikTok starts with a tap and ends with second thoughts. Everything in between feels tedious as your decision is repeatedly challenged.

Although you insist that your decision is permanent, the app still prompts you to review all your data, click through another confirmation screen, and consider deactivating your account instead....Read more

Parmy Olson: ChatGPT-5 hasn't fully fixed its most concerning problem

Sam Altman has a good problem. With 700 million people using ChatGPT on a weekly basis — a number that could hit a billion before the year is out — a backlash ensued when he abruptly changed the product last week.

OpenAI’s innovator’s dilemma, one that has beset the likes of Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Apple Inc., is that usage is so ...Read more

Commentary: The heat-safety law isn't enough. Farmworkers are still dying every summer

By midmorning in the Central Valley, the light turns hard and white, bleaching the sky and flattening every shadow. The rows of melons stretch to the horizon, vines twisted low in cracked soil. Pickers move in the rhythm the crop demands — bend, twist, lift, drop — their long sleeves damp with sweat, caps pulled low, bandanas hiding heat-...Read more

Jackie Calmes: Donald Trump makes America worse than tacky

For President Donald Trump, it's all about appearances.

He's busy with so many makeovers: The Versailles-ification of the Oval Office, which seems to sprout more gold leaf and ornamentation every time Trump assembles the media there. The paving of the Rose Garden, now Mar-a-Lago Patio North, crowded with white tables and yellow umbrellas just ...Read more

Commentary: The true cost of abandoning science

Any trip to the dark night skies of our Southern California deserts reveals a vista full of wonder and mystery — riddles that astrophysicists like myself spend our days unraveling.

I am fortunate to study how the first galaxies formed and evolved over the vast span of 13 billion years into the beautiful structures that fill those skies. NASA...Read more

Commentary: Let voters, not politicians, decide elections

The effort in Texas to hastily redraw congressional maps for partisan advantage reveals vulnerabilities in our democratic system, subject to exploitation by bad actors. As this crisis escalates into multiple states, it threatens the notion that voters should determine who wins elections.

Driving the effort to rig these maps is President Donald ...Read more

Mark Gongloff: Pope Leo is becoming the climate champion we need

While the leader of 340 million Americans furiously works to derail climate action, the leader of 1.4 billion Catholics is embracing it.

In May, when Pope Leo XIV succeeded the late Pope Francis, I suggested he could be the kind of climate champion the world needs when President Donald Trump seems determined to turn the U.S. from one of the ...Read more

Michael Hiltzik: Trump's deal with Nvidia puts our national security on sale to the highest bidder

One thing that can be said about Donald Trump's transactional approach to policy-making is that, as destructive as it might be to our economic health, it gives business leaders clear options to get what they want out of the White House.

The latest case-in-point are the deals struck by chipmakers Nvidia and AMD to secure licenses to export their...Read more

Ronald Brownstein: How to avoid a gerrymandering war

The nakedly partisan congressional redistricting effort that Texas Republicans are pursuing at President Donald Trump’s command shows what the map-making process should not look like. It’s more difficult to say exactly what an appropriate redistricting process should entail.

Reformers typically place the highest priority on avoiding bias ...Read more

Editorial: Hiding the homeless won't solve the problem

The White House has promised swift action on homelessness. It aims to dismantle encampments, force addicts and the mentally ill into treatment, and yank federal funds from cities that refuse to police tents and open-air drug use. For residents exasperated by sidewalk squalor, that sounds like overdue toughness.

In reality, casting the homeless ...Read more

Steve Lopez: My bathroom scale is rigged, and so are my book sales. Lawsuits and pink slips to follow

I stepped on my bathroom scale the other morning and could not believe the three digits staring up at me.

And I mean that literally — the scale was rigged.

I know this because I've been dieting my butt off, and I swear I've dropped 20 pounds. So the first thing I did was ask my wife whether she messed with the scale as some kind of prank.

...Read more

Commentary: Unlike at Columbia, Trump's attack on UCLA is aimed at taxpayer money

President Donald Trump’s demand for a whopping $1 billion payment from UCLA sent shock waves through the UC system. For those of us on the inside, the announcement elicited a range of responses. Some faculty and staff reacted with horror, others voiced increasing fear about the ongoing assault on academic freedom, and some merely muttered in ...Read more