Weather

/Knowledge

Hurricane center says Atlantic system likely to become tropical depression

The National Hurricane Center on Sunday said a system in the eastern Atlantic could become a tropical depression soon while continuing to keep tabs on one other Atlantic system.

As of the NHC’s 2 p.m. tropical outlook, the system dubbed Invest 97 continued to show signs of organization with expanded showers and thunderstorms as it was about ...Read more

Hurricane center gives high chance 1 of 2 tracked Atlantic systems will develop

The National Hurricane Center on Sunday has given an Atlantic tropical wave a high chance of becoming the season’s next tropical depression or storm while also keeping track of a second system.

As of the NHC’s 8 a.m. tropical outlook, the wave that emerged off the coast of Africa on Saturday has increased showers and thunderstorms as it ...Read more

Fires, storms and blazing temperatures forecast for western US

Fires, storms and the potential for near-record high temperatures across the western U.S. are in the offing for the coming week.

The Gifford Fire, about 125 miles (201 kilometers) northwest of Los Angeles, had burned 113,648 acres and was 21% contained through Saturday, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, ...Read more

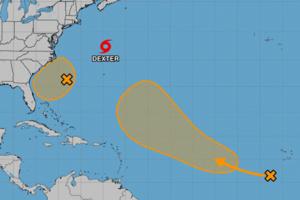

Hurricane center ups odds on new Atlantic system, keeps track of 2nd

ORLANDO, Fla. — The National Hurricane Center on Saturday increased the odds a new tropical wave that has ventured into the Atlantic will develop while also keeping track of a second system that could become the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 8 p.m. tropical advisory, the new system was just off the west coast...Read more

Hurricane center ups odds on new Atlantic system, keeps track of 2nd

ORLANDO, Fla. — The National Hurricane Center on Saturday increased the odds a new tropical wave that has ventured into the Atlantic will develop while also keeping track of a second system that could become the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 2 p.m. tropical advisory, the new system was just offshore of the ...Read more

Hurricane center ups odds on new Atlantic system, keeps track of 2nd

ORLANDO, Fla. — The National Hurricane Center on Saturday increased the odds a new tropical wave that has ventured into the Atlantic will develop while also keeping track of a second system that could become the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 8 a.m. tropical advisory, the new system has emerged offshore of the...Read more

Hurricane center keeps track of 2 Atlantic systems

ORLANDO, Fla. — The National Hurricane Center on Friday continued to keep track of two systems in the Atlantic that could become the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 2 p.m. Eastern time tropical advisory, the closest was a weak area of low pressure located a couple hundred miles offshore of North Carolina with a...Read more

Hurricane center keeps track of 2 Atlantic systems

ORLANDO, Fla. — The National Hurricane Center on Friday continued to keep track of two systems in the Atlantic that could become the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 8 a.m. tropical advisory, the closest was a weak area of low pressure located a couple hundred miles offshore of North Carolina with a few ...Read more

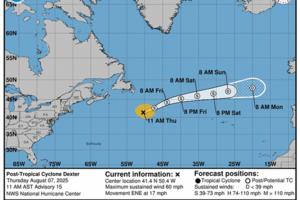

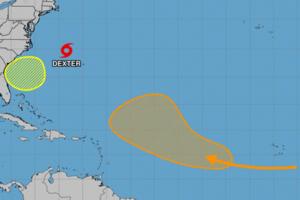

Hurricane center tracks 2 Atlantic systems while Tropical Storm Dexter becomes extratropical

The National Hurricane Center on Thursday said Tropical Storm Dexter had become extratropical, but continued to keep track of two developing Atlantic systems that could become the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 2 p.m. Eastern time tropical advisory, closer to the the U.S. but moving away is what is now expected ...Read more

Hurricane center keeps tracking 2 Atlantic systems while TS Dexter becoming extratropical

The National Hurricane Center on Thursday forecast Tropical Storm Dexter to become extratropical, but continued to keep track of two developing Atlantic systems that could become the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 8 a.m. tropical advisory, closer to the the U.S. but moving away was a weak area of low pressure a ...Read more

SoCal heat wave peaks today, but sweltering temps, fire risk will last for days

LOS ANGELES — The worst of Southern California's ongoing heat wave is expected to land Thursday, but relief is not yet in sight. Temperatures will remain toasty over the weekend, and another hot spell is forecast next week.

Temperatures will hit the triple digits in the San Fernando and Antelope valleys on Thursday, while interior regions of ...Read more

Colorado weather: Red flag, heat and smoke advisories active statewide

DENVER —Dangerous fire conditions, soaring temperatures and smoky skies across Colorado prompted severe weather alerts for parts of the Western Slope, Front Range and Eastern Plains on Wednesday.

Temperatures are expected to reach 100 degrees in Denver, Boulder, the western metro and Fort Collins, National Weather Service forecasters said in ...Read more

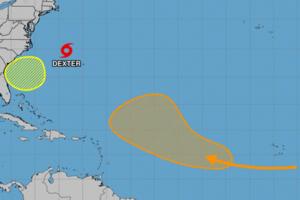

Hurricane center eyes 2 Atlantic systems along with Tropical Storm Dexter

ORLANDO, Fla. — The National Hurricane Center on Wednesday continued to keep track of Tropical Storm Dexter as well as two developing Atlantic systems that could become the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 8 a.m. tropical advisory, the closest system to the U.S. was a weak area of low pressure that had formed ...Read more

Hurricane center increases odds system off Florida will develop amid Atlantic upsurge

ORLANDO, Fla. — The National Hurricane Center on Tuesday increased the chances an expected low pressure area off the northeast coast of Florida could develop into a tropical depression or storm while keeping an eye on another Atlantic system plus Tropical Storm Dexter.

As of the NHC’s 2 p.m. Eastern time tropical outlook, forecasters expect...Read more

Hurricane center increases odds system off Florida will develop amid Atlantic upsurge

ORLANDO, Fla. — The National Hurricane Center on Tuesday increased the chances an expected low pressure area off the northeast coast of Florida could develop into a tropical depression or storm while keeping an eye on another Atlantic system plus Tropical Storm Dexter.

As of the NHC’s 8 a.m. tropical outlook, forecasters expect a weak ...Read more

Hurricane center eyes potential systems near Florida, in Atlantic while TS Dexter churns

The National Hurricane Center on Monday increased the odds two systems could form into the season’s next tropical depression or storm, including one near Florida’s coast, while newly formed Tropical Storm Dexter continued to churn in the Atlantic.

As of the NHC’s 2 p.m. Eastern time tropical outlook, forecasters expect a broad area of low...Read more

Hurricane center eyes potential systems near Florida, in Atlantic while TS Dexter churns

ORLANDO, Fla. — The National Hurricane Center on Monday increased the odds two systems could form into the season’s next tropical depression or storm, including one near Florida’s coast, while newly formed Tropical Storm Dexter continued to churn in the Atlantic.

As of the NHC’s 8 a.m. tropical outlook, forecasters expect a broad area ...Read more

Hurricane center tracks 3 Atlantic systems that could develop

The National Hurricane Center continued Sunday to track three systems in the Atlantic with the potential to form into the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 2 p.m. tropical outlook, it had increased chances for a system off the U.S. East Coast to form while also forecasting a tropical wave to roll off the African ...Read more

Hurricane center tracks 2 Atlantic systems that could develop

The National Hurricane Center continued Sunday to track two systems in the Atlantic with the potential to form into the season’s next tropical depression or storm.

As of the NHC’s 8 a.m. tropical outlook, it had increased chances for a system off the U.S. East Coast to form while also forecasting a tropical wave to roll off the African ...Read more

One dead from severe Charlotte-area storms. Thousands without power on Saturday

CHARLOTTE, N.C. — A driver died in a two-car wreck during intense storms that swept across the Charlotte region Friday night, a State Highway Patrol trooper said.

Gabriella Elise Cruz, 22, of Bryson City, died at the scene on Interstate 40 West in Claremont, Master Trooper Christopher Casey said in a news release.

An SUV driver collided with...Read more

Popular Stories

- Hurricane center says Atlantic system likely to become tropical depression

- Fires, storms and blazing temperatures forecast for western US

- Hurricane center gives high chance 1 of 2 tracked Atlantic systems will develop

- Hurricane center ups odds on new Atlantic system, keeps track of 2nd

- Hurricane center keeps track of 2 Atlantic systems