We asked a Nobel Prize-winning economist how to fix fintech

Published in Science & Technology News

Financial services, like many institutions, are losing Americans’ trust. That’s a problem. Economies depend on a healthy financial system, as became painfully evident during the 2008 financial crisis, and that system operates largely on trust — confidence that people can access the money in their bank accounts, that their investment accounts are secure, and that their trades will be filled at quoted market prices, to name just a few everyday financial interactions.

But building confidence in financial services is tricky. Financial systems are technical and complex and therefore somewhat opaque, and that opacity erodes trust. Financial technology from online trading and blockchain to mobile payments and banking has the potential to make financial services more transparent and trustworthy, but it’s not yet clear if, or to what extent, those innovations are making a difference.

Take blockchain, for example. Its proponents argue that trust isn’t necessary because a decentralized network of computers verifies and collectively stores transactions, making the record tamper-proof. Even so, I suspect few people understand how blockchain works, or how to mine or store digital coins. That may explain why many investors own cryptocurrencies through financial intermediaries such as crypto exchanges and banks, or more recently exchange-traded funds, all of which require no less trust than traditional financial services.

Now add artificial intelligence to the mix. AI could conceivably make financial services more accessible but also less transparent.

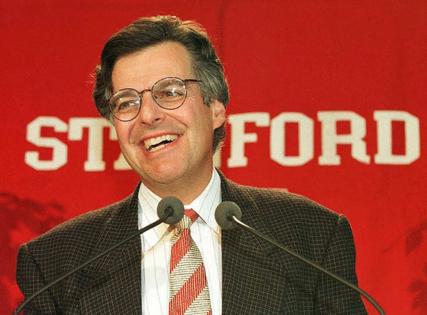

To better understand how these new technologies might affect our trust in the world of finance, I spoke to Myron Scholes, who together with Robert C. Merton won a Nobel Prize in economics in 1997 for a method to determine the value of derivatives and has been thinking deeply on the subject of trust for decades. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our correspondence:

Nir Kaissar: Myron, how would you characterize the level and directionality of trust in financial services?

Myron Scholes: In my view, lack of trust and uncertainty go hand in hand. It is difficult for investors to separate the truth from fiction. Uncertainty masks the truth. Many products are offered to investors showing high rates of return. Although there are always caveats claiming that future returns are not guaranteed and could differ from past results, how is the investor to know whether the results shown are not data-mined — found by searching the past for the best results or seeding a bunch of alternatives and then showing actual results on the best of them that randomly generated good returns?

Increases in the levels of uncertainty in the financial system have led to an erosion of trust, especially when the promised good results don’t materialize. Tail events or downside shocks expose products that suffer large losses in bad times while making smaller gains most of the time. To garner extra returns, investors have sold put options that need to be paid off with market drawdowns. With higher levels of uncertainty, products are offered that make promises that have a low probability of success. This makes it difficult and costly for honest product providers to distinguish themselves from the cheaters. Many products that should be developed for investors are not: It becomes too costly to build trust.

Nir Kaissar: In that regard, new financial products, which are almost always marketed as an improvement, run the risk of making it harder for investors and consumers to navigate the financial system. One example is the explosion in the number of ETFs in recent years. That raises the questions: Is financial technology building or eroding trust in financial services? And does fintech make trust more or less important?

Myron Scholes: All new innovations precede the infrastructure to govern them. Under uncertainty, it is difficult to ascertain which innovations will be successful. It would be too expensive for financial institutions to set up all the controls and constraints that eventually come into being for successful products that demonstrate sustainability. This means that newer projects attract cheaters to game the system.

We saw that recently with cryptocurrencies and the many coins that were developed and failed. We see that with the rush into AI-generated financial solutions and products. Financial (or business) innovations are brought forward if they can provide services faster, more individualized, and more flexibly. With more uncertainty, flexibility gains value, offering the ability to change with changing circumstances and new desired outcomes. With technology, financial companies can offer services more tailored to satisfy a given investor or provide a specific solution, rather than to focus on selling a particular product.

Moreover, no one wants to wait too long for a solution to their problem. Some other financial entity will provide it soon. Speed, individualization and flexibility are cornerstones of innovations if they can be provided at lower cost. Technology facilitates each of these. But the move to more of a focus on solutions requires trust. Individuals must trust their financial advisers, who have more acumen than they do, to design and implement the solution and allow for flexibility as needs change.

This is objective-based, client-focused, a bottoms-up and not a top-down approach. This is where financial innovation and services are heading. Fintech is facilitating this evolution.

Nir Kaissar: So, how do we reconcile the uncertainty created by new financial products with the higher level of trust that these new, technology-based products require? How should financial services companies build trust, and what role does technology play?

Myron Scholes: Technology is a tool to innovate and to monitor. Institutions that have a long history of innovations that monitor cheaters and control their offerings are more likely to be successful. To maintain trust, their rate of innovation most likely will be slow and monitored. They will educate clients. They will be cautious. They need to protect their reputations. They put constraints on the innovation process. This takes longer for the educational process to unfold and the rollout of new services is slower and less flexible.

Financial technology helps the education and trust-building process within and outside entities. Learning and trust building need to occur within organizations. Learning occurs from one-on-one communication from entity to client and from fellow investors to fellow investors. Clients compare across financial entities. Most advisers interact with clients to educate and understand their requirements to fashion solutions for them. They use the reputation of their firms to grow and maintain client relationships. They use the track records of similar offerings to build trust.

New technology and new innovations, however, can break through the governing constraints of old infrastructure by providing more idiosyncratic services faster and more individualized. Older in-house infrastructure may be far more costly than newer fintech. Clients trade off the lower-cost offerings of new innovators with the cost of developing trust to use those new offerings. With success, the new offerings displace the old and the cycle repeats itself.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments