Science & Technology

/Knowledge

Biden creates 2 vast national monuments during final week in office

President Joe Biden on Tuesday created two new vast national monuments in California’s desert and far north that protect lands considered sacred by tribes, bolstering his conservation legacy days before leaving office.

Biden signed proclamations establishing the 624,000-acre Chuckwalla National Monument south of Joshua Tree National Park in ...Read more

$20 billion Delta tunnel plan wins endorsement from Silicon Valley's largest water agency

SAN JOSE, Calif. — Gov. Gavin Newsom’s $20 billion plan to build a massive, 45-mile long tunnel under the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to make it easier to move water from Northern California to Southern California won the endorsement of Silicon Valley’s largest water agency on Tuesday.

By a vote of 6-1, with director Rebecca Eisenberg ...Read more

Firefly looks to punch NASA moon ticket with overnight SpaceX launch

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — A SpaceX mission set to lift off overnight marks a first for Firefly Aerospace under NASA’s plans to build up American companies to support its lunar goals.

A Falcon 9 targeting a 1:11 a.m.Eastern time, liftoff Wednesday from KSC’s Launch Pad 39-A is carrying the Cedar Park, Texas-based company’s Blue Ghost lunar ...Read more

EPA warns of toxic forever chemicals in sewage sludge used on farmland, including thousands of acres near the Chicago area

CHICAGO — Farmers who use sewage sludge as fertilizer and their neighbors face higher risks of cancer and other diseases, according to a new federal analysis that pins the blame on toxic forever chemicals.

The findings are particularly relevant for northeast Illinois, where more than 777,000 tons of sludge from Chicago and Cook County have ...Read more

Mega data centers are coming. Their power needs are staggering

Facebook’s parent company is building Minnesota’s first mega data center in Rosemount to house its fast-growing need for computing muscle.

Amazon and Microsoft bought land for large data centers near Xcel Energy’s soon-retiring coal plant in Becker. A Colorado company called Tract has advanced a project in Farmington and is eyeing ...Read more

Colorado to start regulating emission of 5 air toxins that make people sick

DENVER — Colorado air pollution regulators spend a lot of time thinking about greenhouse gases that create a smog across the Front Range and contribute to global warming, But this week, they’ll focus on five toxic chemicals that make people sick.

Five new compounds soon will be listed as priority toxic air contaminants in Colorado and, ...Read more

China discusses sale of TikTok US to Musk as one possible option

Chinese officials are evaluating a potential option that involves Elon Musk acquiring the U.S. operations of TikTok if the company fails to fend off a controversial ban on the short-video app, according to people familiar with the matter.

Beijing officials strongly prefer that TikTok remains under the ownership of parent ByteDance Ltd., the ...Read more

San Jose water agency to vote on whether to help fund Gov. Gavin Newsom's $20 billion Delta tunnel project

SAN JOSE, Calif. — Silicon Valley’s largest water agency will vote Tuesday on whether to support Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan to spend $20 billion to build a massive, 45-mile long tunnel under the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to make it easier to move water from Northern California to Southern California.

The board of the Santa Clara Valley ...Read more

Climate change threatens Miami real estate. The new appraiser wants lower taxes for that

MIAMI — Miami-Dade’s newly elected property appraiser says it’s time for county property estimators to factor in the harm that climate change will bring to the local real estate market — and to lower property values accordingly.

“When we look to consider the future value of a property, we should also start considering location, ...Read more

Maryland Port Administration to launch multi-year, $147 million project to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

BALTIMORE — The Maryland Port Administration said Monday that it is beginning preliminary work on a multi-year, federally funded $147 million project to reduce greenhouse gas emissions at the Port of Baltimore.

The funds are part of a $3 billion national investment in ports that was part of the Inflation Reduction Act signed by outgoing ...Read more

LA fires: Fast wildfires are more destructive and harder to contain

Investigators are trying to determine what caused several wind-driven wildfires that have destroyed thousands of homes across the Los Angeles area in January 2025. Given the fires’ locations, and lack of lightning at the time, it’s likely that utility infrastructure, other equipment or human activities were involved.

California’...Read more

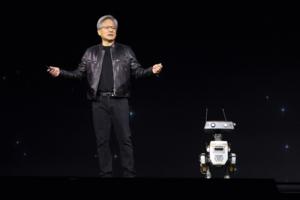

White House unveils new curbs on exporting Nvidia AI chips

The White House unveiled sweeping new limits on the sale of advanced AI chips by Nvidia Corp. and its peers, leaving the Trump administration to decide how and whether to implement curbs that have encountered fierce industry opposition.

The rules, which are set to take effect in one year, establish caps on the amount of computing power that can...Read more

Sonos CEO to step down after disastrous app overhaul

Sonos Chief Executive Patrick Spence is stepping down and leaving the company’s board in a shake-up that comes as the wireless speaker maker tries to win back the trust of its customers.

Last year, the Santa Barbara-based company botched the overhaul of its phone app that customers use to control their speakers and other audio products. The ...Read more

Washington Legislature considers climate, environmental bills this session

SEATTLE — Don't expect any grand or sweeping climate and environmental laws out of Washington's Capitol during this long legislative session, starting Monday.

Rather, this session is largely about "implementation," said state Rep. Joe Fitzgibbon, D-Burien. That is to say, it's about making sure the state's current policies and initiatives —...Read more

SpaceX sends up 5th Space Coast launch of the year

SpaceX knocked out another launch on Monday sending up the fifth Space Coast mission of the year.

A Falcon 9 rocket carrying 21 satellites took off through overcast skies at 11:47 a.m. from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s Space Launch Complex 40.

The first-stage booster for the mission made its 15th flight with a recovery landing ...Read more

Firefighting planes are dumping ocean water on the Los Angeles fires − why using saltwater is typically a last resort

Firefighters battling the deadly wildfires that raced through the Los Angeles area in January 2025 have been hampered by a limited supply of freshwater. So, when the winds are calm enough, skilled pilots flying planes aptly named Super Scoopers are skimming off 1,500 gallons of seawater at a time and dumping it with high precision on the ...Read more

One way Trump could help revive rural America’s economies

Picture yourself living the American Dream. You likely have more opportunity than your parents did. Through hard work, smart choices and perhaps some good luck along the way, you have financial stability and a great deal of freedom to choose your next steps in life.

Chances are also good that you live in or near a vibrant community ...Read more

Apex predators captured in Canada to be flown to Colorado and released. Here's why

Wildlife experts are in the process of capturing gray wolves from Canada in order to release them in Colorado, effectively doubling the state’s small, recently reintroduced population.

Until recently, gray wolves were virtually extinct in Colorado, but state officials are going to great lengths to change that.

As many as 15 gray wolves will ...Read more

Blue Origin now shooting for early Monday debut launch of New Glenn rocket

Blue Origin pushed again its planned debut launch of its New Glenn rocket from the Space Coast, now targeting an early Monday morning liftoff.

The 321-foot-tall rocket making its debut on the NG-1 mission is targeting a three-hour window from 1-4 a.m. Monday for liftoff from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s Launch Complex 36.

It had been...Read more

From watts to warheads: Secretary of energy oversees big science research and the US nuclear arsenal

The U.S. Department of Energy was created in 1977 by merging two agencies with different missions: the Atomic Energy Commission, which developed, tested and maintained the nation’s nuclear weapons, and the Energy Research and Development Administration, a collection of domestic energy research programs.

Today the department ...Read more

Popular Stories

- China discusses sale of TikTok US to Musk as one possible option

- Mega data centers are coming. Their power needs are staggering

- Colorado to start regulating emission of 5 air toxins that make people sick

- San Jose water agency to vote on whether to help fund Gov. Gavin Newsom's $20 billion Delta tunnel project

- EPA warns of toxic forever chemicals in sewage sludge used on farmland, including thousands of acres near the Chicago area