How trains linked rival port cities along the US East Coast into a cultural and economic megalopolis

Published in Science & Technology News

The Northeast corridor is America’s busiest rail line. Each day, its trains deliver 800,000 passengers to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington and points in between.

The Northeast corridor is also a name for the place those trains serve: the coastal plain stretching from Virginia to Massachusetts, where over 17% of the country’s population lives on less than 2% of its land. Northeasterners ride the corridor and live there too.

Like “Rust Belt,” “Deep South,” “Silicon Valley” and “Appalachia,” “Corridor” has become shorthand for what many people think of as the Northeast’s defining features: its brisk pace of life, high median incomes and liberal politics. In 1961, Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona wished someone had “sawed off the Eastern Seaboard and let it float out to sea.” In 2016, conservative F.H. Buckley disparaged “lawyers, academics, trust-fund babies and high-tech workers, clustered in the Acela Corridor.”

As a scholar of language and literature, I’m interested in what words can teach us about places. My new book, “The Northeast Corridor,” shows how America’s most important rail line has shaped the Northeast’s cultural identity and national reputation for almost 200 years. In my view, this bond between transit and territory will only strengthen as new federal investments in passenger service draw more Northeasterners aboard trains.

The first American railroads were stubs – strap iron curiosities that hauled marble, granite and coal in winter months when canals froze. It was not until 1830 that the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad opened the nation’s first public passenger line.

Railway mania ensued. Within a few years, trains were crisscrossing the Eastern Seaboard. A new periodical, The Railroad Journal, predicted that tracks would one day form a “great chain which, is in our day to stretch along the Atlantic coast, and bring its chief capitals into rapid, constant, and mutually beneficial relation.”

The Boston & Providence Railroad forged one link of this chain in New England. The Philadelphia & Trenton cast another in Pennsylvania, and the Philadelphia, Wilmington, & Baltimore hammered out a third through Delaware and Maryland. Named for the cities they linked, these carriers helped turn a collection of rival ports into a cohesive economic unit.

Despite their rapid growth, each railroad remained a separate fiefdom beset by its own state mandates, financial shortfalls and technological limitations. An antebellum train trip from Baltimore to New York would have required multiple transfers and two ferry rides, and taken most of a day.

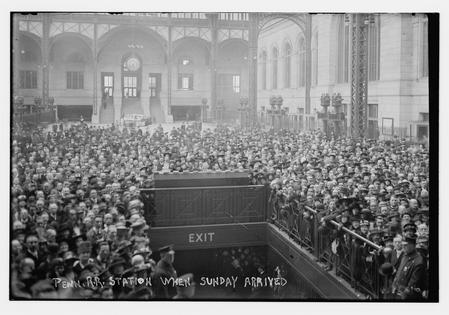

The “great chain” began to take modern shape in the late 19th century as corporate consolidations created two highly resourced super carriers: the New Haven and Pennsylvania railroads. Engineering advances permitted the construction of new bridges, embankments and terminals. With the opening of a tunnel under the Hudson River from New Jersey to Manhattan in New York City in 1910, and a bridge over Hell Gate Strait between the New York boroughs of Queens and the Bronx in 1917, trains could roll continuously between New England and the Chesapeake region.

Railroading became a way of life for Northeasterners. Physicist Albert Einstein liked watching trains click-clack through Princeton Junction during his time at Princeton University’s Institute for Advanced Study in the 1930s and 1940s.

...continued

Comments