Shedding light on the unique trauma of a Holocaust survivor’s child

Published in Mom's Advice

There’s a school of thought that argues how important it is for the remaining Holocaust survivors to discuss their experiences while they still can, so that subsequent generations can learn from the past. Studies have supported this line of thinking.

Estimates tag the remaining number of Jewish Holocaust survivors at about 245,000. But try to imagine the pain and difficulty for them to relive the atrocities of the past that they witnessed firsthand.

Psychologists say the silence surrounding their experiences, while having a profound effect on their lives, could also affect the next generation. Children of survivors were often raised in environments marked by unspoken trauma, often leading to anxiety, hyper-vigilance and PTSD symptoms in the children themselves.

That’s how Mitchell Raff grew up. His family, sufferers of the Holocaust, “believed that silence — suppressing the horrors visited upon them in their young lives — could cauterize their wounds and insulate” he and his sister.

“Naively,” Raff writes, “I thought I could refuse this inheritance, but it doesn’t work that way. Sometimes you can’t choose what you inherit, and my birthright included those wounds.”

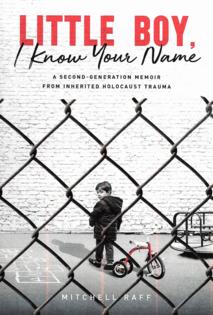

That’s the backdrop behind Raff’s riveting book "Little Boy, I Know Your Name," a second-generation memoir from inherited Holocaust trauma.

For much of his childhood, Mitchell lived in fear and was beaten and humiliated by his mother, seemingly without good reason. In so many ways, that mirrors the life of a concentration camp survivor: being considered unworthy and undeserving of respect, compassion or life itself, and living in that constant state. Life was a minefield.

Just consider the life of Raff’s mother: parents divorced, Nazis invade her home, she watches her own mother die, lives in loneliness, confined spaces, in constant fear of being captured. And she’s not even a teenager yet.

These vivid images are what followed the author to his adult life, with the hope of overcoming the trials and traumas of Issa and Sally, his beloved uncle and aunt who raised him, and his own father and mother. It’s not something for which people can snap their fingers and make this influence on them go away.

Raff as a four-year-old lived in Los Angeles with Issa and Sally until one day, through the fence at a playground, an old, frail woman calls the young boy over and declares “Little boy, I know your name.” It’s his mother, who assumes custody of the child and in the process removes any love and contentment from his upbringing. Eventually, she takes the boy and his sister to Israel, where they are placed in other homes and attend schools where the primary language is Hebrew. Eventually, Issa and Sally rescue him and take him back.

The effects of Raff’s childhood and upbringing carry through to adulthood. “It was impossible to expect I could take all the hits of my childhood and not bleed or break.”

He marries a girl outside the Jewish religion, tries to find a trade for a career, and has a son. The scars remain, and he goes down a difficult path. And there’s the effect on the third generation as well.

Mitchell Raff is a gifted storyteller who, by writing this book, relives his own story in a manner that his ancestors could not. He is talented in recreating the settings, emotions and actions that had such a profound effect on him. And he reveals a side of the Holocaust — the effects on the next generation — that are not conveyed enough in literature and formal studies. His story is so personal, authentic and heartbreaking.

"Little Boy, I Know Your Name" must have been a hard book to write but an important story to tell. And Raff tells it quite well.

As the author laments, “The Holocaust is a weirdly absent parent. We feel its presence but never enough to truly know it.”

Comments