A Catholic hospital sent this risky miscarriage patient home. Did it break California law?

Published in Health & Fitness

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Rachel Harrison and Marcell Johnson were elated to have a baby. It would be the first for the couple, who have been together nearly 10 years and were looking forward to starting a family.

In September, when she was a little more than 17 weeks pregnant, Harrison was at home when she felt a gush of fluid. As the couple, both 29, readied to go to the hospital, Harrison also discovered blood and clotting.

They rushed to Mercy San Juan Medical Center, the hospital closest to their Carmichael home and the place Harrison had selected to give birth.

But in the labor and delivery clinic, Harrison was turned away because she was not yet 20 weeks along. She was sent to the emergency room, where she and Johnson waited hours to be seen.

“I had a feeling, you know, woman’s intuition, that something isn’t right,” Harrison said.

But she kept hoping her baby would be OK.

Harrison, herself born at 24 weeks to a mother addicted to drugs, had researched pre-term birth extensively after an earlier scare in her pregnancy and found that babies can sometimes be delivered as early as 18 weeks, though the odds of survival are low.

So she and Johnson prayed and hoped for the best. “We’re very spiritual people and we believe in God,” she said.

Finally, after blood tests and an ultrasound, the couple was told Harrison had lost all amniotic fluid. The baby’s heart rate was low and it would likely not survive.

The medical team at the Catholic-affiliated hospital told her that they could not help. A surgical abortion – known as a dilation and evacuation – could remove the tissue, but Mercy San Juan would not perform it because fetal heart tones were detected.

While California has some of the most expansive abortion access laws in the country, they include exceptions for religious or moral reasons. These exceptions – which courts have upheld as a religious freedom protection – can lead to gaps in care for patients like Harrison and questions over when and how they are applied. And in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court decision that overturned nationwide abortion rights, the exemptions in California have come under new scrutiny by state lawmakers eager to expand protections for reproductive care.

For Harrison, the hospital advised she go home and miscarry without medical intervention.

Johnson, her longtime partner, said he was struck by the instructions they were given: pass the fetus and dispose of it at home. By that point in Harrison’s pregnancy, the baby was about the size of an avocado. They only told her to return if her symptoms worsened.

“That was really hard for me to deal with and comprehend. I was really angry and frustrated. I couldn’t imagine someone (saying) go home and flush your baby down the toilet, essentially,” he said.

‘Very high risk of complications’

Most miscarriages, about 80%, happen during the first 14 weeks of pregnancy. In the second trimester, a miscarriage – particularly one in which a person’s water breaks or they experience labor-like symptoms – are rarer, and riskier, said Dr. Holly Rankin, a fellow at UC Davis Health who specializes in complex family planning.

“People who break their water early are at very high risk of complications,” she said, including heavy blood loss and infection.

A spokesperson for Dignity Health, the nonprofit health system that operates Mercy San Juan, said it does not comment on specific patient cases due to privacy laws.

“At Dignity Health Mercy San Juan Medical Center, our goal is to provide the highest quality care to all patients. When a pregnant woman’s health is at risk, appropriate emergency care is provided,” the spokesperson said in an email.

Rankin said Harrison’s symptoms – broken water and bleeding – are consistent with preterm premature rupture of membranes, or PPROM. In that scenario, it’s safest to remove all tissue from the uterus to prevent dangerous blood loss, infection, or in extreme cases, sepsis.

“Passing a 17-week pregnancy at home is not really recommended,” Rankin said. “People are going to have significant pain, significant bleeding, and could have a retained or left behind placenta, which again causes ongoing bleeding and pain.”

Rankin called Harrison’s case “really upsetting” and said ideally, she would have been seen by an obstetrician who could evaluate her.

“This is a rare situation but it is one that every OB/GYN should know how to manage and should know how to counsel a patient appropriately,” she said. “Even at a Catholic institution, if they’re not able to provide (an abortive procedure) or induction because there are heart tones, then they must expeditiously transfer a patient to a place that can do that care. That is the standard of care.”

Catholic hospitals deny miscarriage care

Harrison’s case is the second in recent months to come to light in which a Catholic-affiliated hospital in California declined to provide a patient with abortion care.

In September, Attorney General Rob Bonta filed a lawsuit against Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Humboldt County, alleging the hospital illegally “dumped” a patient onto another clinic.

The patient in that case, Anna Nusslock, was pregnant with twins and also had her water break early, at 15 weeks. She also experienced heavy bleeding.

Doctors at Providence told Nusslock that she risked infection or death if her pregnancy was not immediately terminated, but said hospital policy prevented them from providing that care because fetal heart tones could be detected from one of the twins. The heavily bleeding Nusslock was handed a bucket of towels and sent to a smaller clinic 20 minutes away.

After Bonta’s lawsuit, Providence St. Joseph agreed to provide emergency abortions if a patient’s life or bodily function would be seriously jeopardized without one.

A spokesperson for Bonta declined to comment on Harrison’s case but said in a statement:

“Abortion care is healthcare; and in California, access to abortion care is a constitutionally protected right. The Attorney General will always defend reproductive rights, and will continue to use the full force of his office to hold accountable those who break the law.”

In the two years since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, California’s Democratic-led legislature has worked to remove barriers for abortion access and voters added the right to an abortion to the state constitution.

It’s a far contrast from states including Texas and Georgia, where pregnant women have died after delayed or denied emergency care.

California allows hospitals and individual providers to refuse to perform an abortion on religious or moral grounds, but there’s gray area.

According to the ACLU of Northern California, religious exemptions in the state don’t apply in cases of medical emergencies or pregnancy loss. Bonta’s office affirmed that hospitals are required to perform emergency abortions, but would not respond to questions about whether religious exemptions apply during pregnancy loss episodes.

Harrison has contacted the attorney general’s office about her experience at the hospital. The office declined to comment on whether they were investigating the case.

President-elect Donald Trump has said he is fine with leaving abortion up to individual states to regulate as they please. Still, advocates for reproductive rights are concerned his administration may move to further restrict abortion rights by banning mail-order abortion pills or imposing other limits.

Democratic Assembly member Mia Bonta, who is married to Attorney General Rob Bonta, said she plans to introduce a bill in the upcoming legislative session to ensure emergency reproductive care is covered under California’s emergency room care laws.

“It’s very important that we’re proactive and clear in our statute,” she said. “What we don’t want to have happen is a chilling effect that keeps people from getting the health care that they need.”

It’s unclear whether Harrison’s case was or should have been considered an emergency, since she was not in extreme pain or bleeding heavily. But the denial of care put her at greater risk for that, Dr. Rankin said.

‘They failed us’

“I don’t know what to do,” Harrison recalled repeating in the Mercy San Juan emergency department in September.

Though the physician assistant advising her was kind, she said she didn’t get the care or guidance she needed after six hours at the hospital.

“At that point there was nothing they could do. So we just got the discharge papers and then came home,” she said.

After resting for a few hours, Harrison began having contractions. The couple went to Kaiser Permanente Sacramento after family members urged them to get a second opinion. There, Harrison was seen immediately and the hospital administered blood tests, an ultrasound and a pelvic exam.

“Doctors came in and they said that at this point, the baby did pass away,” she said, pausing to wipe tears from her eyes.

The doctors recommended she undergo dilation and curettage, a procedure to remove the fetus and placenta, sometimes referred to as a surgical abortion.

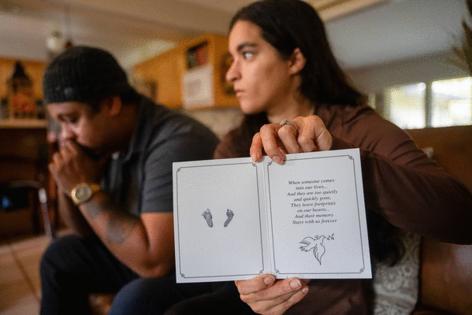

It was over quickly. When Harrison woke up, she was given a card stamped with her baby’s tiny footprints. The hospital arranged to cremate the remains of their baby, a boy. They had already started collecting clothes and supplies for him.

“This, to me, means more than just someone telling me to flush my baby down the toilet,” said Johnson, holding the white container with their baby’s ashes. “At least he can still be with us in some fashion.”

Soon after the episode, Harrison dealt with the unexpected and heartbreaking realities of miscarriage: “I didn’t know I was gonna have breast milk. So that was really hard, emotionally and physically,” she said.

They put the baby clothes and diapers they had begun to collect in a cabinet, out of sight.

“As first time parents, we went to Mercy San Juan to get help and for them to guide us,” she said. “They did not. I feel like they failed us as individuals, as two people going there to get help.”

The couple eventually wants to try for another baby but the emotional pain still lingers, Harrison said. “It’s not something that I think is going to go away immediately. We obviously still have to heal from it.”

©2024 The Sacramento Bee. Visit at sacbee.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments