Can 'magic' mushrooms help one of the most painful conditions?

Published in Health & Fitness

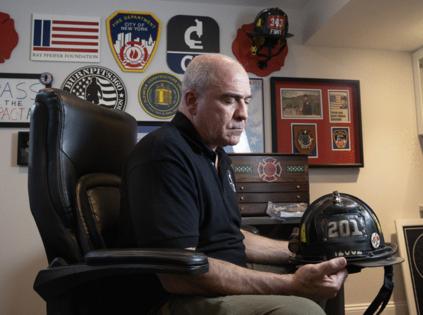

PHILADELPHIA — Joe McKay tried everything medicine had to offer for the blinding headaches that began in the months after 9/11, when the former New York City firefighter spent weeks wading through the curtains of dust and smoke at the World Trade Center.

On his worst days, McKay was incapacitated by pain every few hours, feeling like someone had stabbed him in the eye with an ice pick. "It's the worst pain I've ever felt," he said.

He tried numerous prescription medications without lasting relief. Doctors diagnosed him with a condition called cluster headaches, also known as "suicide" headaches for the despair experienced by suffers.

Then McKay heard about an unusual treatment that some cluster headache patients swore by: psilocybin, the psychedelic chemical found in "magic" mushrooms.

McKay called a friend who knew someone who used to go to Grateful Dead concerts, and, in his backyard in Monmouth County, N.J., took a nibble of a chocolate he was told contained psychedelic mushrooms. He felt a bit "blissful," and it seemed to help keep his headaches at bay. When the symptoms came roaring back, and nothing else seemed to work, he learned about a specific protocol for psilocybin developed via a grassroots effort from cluster headache patients, then tried again.

The next day, he felt the shadows of a cluster headache attack, but it never came. Same with the day after. McKay's headaches didn't return for a year.

The experience gave him something he hadn't had for a very long time: hope. "I can live with this," he thought. "I had something that worked."

That's not how medicine is supposed to happen. Psychedelic drugs that are illegal aren't supposed to work better than prescription medications, backed by reams of research data.

But for McKay and many other people with cluster headaches, that's the reality.

Now, science is slowly catching up to what patients are experiencing in backyards all over the globe, and preliminary research is showing that, for some, psilocybin could be a game-changing treatment for cluster headaches. Scientific studies are vetting its potential — along with other psychedelic drugs — for other hard-to-treat conditions like mental illness.

When it comes to psilocybin and cluster headaches, some academics are aided by a grassroots, advocacy organization known as Clusterbusters (McKay is now on the board), which developed instructions on how to grow your own mushrooms from spores (legal to purchase in Pa., just not to grow), and a protocol for how to use low, non-hallucinogenic doses to treat and prevent cluster headaches.

"There's really compelling evidence that [psilocybin] is efficacious and safe and seems to help people" with cluster headaches, said Dominic Sisti, associate professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania. "There's really no reason why we ought not look into it further."

'Prayed for death'

It's not clear what causes the crushing pain associated with cluster headaches, nor why psilocybin might help.

Research on cluster headaches suggests they may stem from a surge of certain chemicals near a nerve that transmits information between the face and brain, or from problems in the brain region known as the hypothalamus. This is also the region of the brain that psilocybin appears to act on, limited research on psychedelics is showing.

Cluster headaches affect fewer than 1 in 1,000 adults — including Tom, a therapist in private practice in his mid-60s who works in Montgomery County. His headaches began in December, 2008, and are unbearable. In a 2020 survey, cluster headache patients reported the pain is worse than every other condition, such as unmedicated childbirth, kidney stones, and getting shot. "There were times where I prayed for death," said Tom, who declined to provide his last name to protect his professional license. "I prayed for God's mercy to take me out."

Over the years, he's tried various prescription medications, which would work for a while, until the headaches came thundering back.

He heard about people who used psilocybin, but as a recovering alcoholic, he was leery of illegal drugs that produced psychedelic experiences.

Psilocybin, MDMA (also known as Ecstasy or Molly), and LSD are all considered psychedelics because, at certain doses, users can hallucinate.

Tom learned that firsthand, when he finally decided to give psilocybin a try in 2022. "I felt like the light was brighter. Colors were sharper, more vibrant."

He still uses psilocybin sometimes — as a way to stay pain-free for longer, and a complement to the multiple prescription drugs he takes, not as a way to get high. "I'm not over here partying and having a good time. For me, it's medicine, and I really do think of it as medicine," Tom said.

With the gaps in knowledge about psilocybin come gaps in understanding about its potential risks: Although the data suggest psilocybin is generally well tolerated, people who have bipolar disorder (or a family history of it) may exhibit more psychotic symptoms after taking psychedelics than people without that history.

Tom has only told a few people he takes "magic" mushrooms, and even hesitated sharing it with his neurologist. But the doctor didn't have a problem with it. "'I just won't put it in your record,'" he told Tom.

"I was shocked," Tom said.

Research roadblocks

Psychedelics such as psilocybin and ayahuasca have been used medicinally for thousands of years in indigenous communities. But the U.S. has classified psilocybin as an illegal substance in the most restrictive category, along with heroin and LSD (another type of hallucinogen that research suggests could have some health benefits, including for cluster headaches). This makes it difficult to conduct research studies using psilocybin.

Despite this roadblock, scientists have managed to investigate the potential benefits of psychedelics, and generated early data showing they could help conditions ranging from depression to addiction to PTSD. In 2021, a clinic opened up in West Philly, offering psychedelic-assisted therapy.

That said, psychedelics have a certain "hype bubble" around them at the moment, said Penn's Sisti. Some people claim the drugs will cure many ailments, although they have little (if any) supporting evidence.

And neither regulators nor most members of the public appear convinced they should be widely used as medicine. In August, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration declined to approve a treatment that combined MDMA with psychotherapy for PTSD, and on Election Day, voters in Massachusetts (a fairly liberal state) rejected a ballot measure to allow people to grow psilocybin at home.

The fact that psilocybin remains illegal to grow and use likely deters some cluster headache patients from trying it, writes Joanna Kempner in her 2024 book "Psychedelic Outlaws," about the cluster headache patient community. One advocate Kempner spoke with said she hears from many patients of color who worry about getting caught by police.

One cluster headache patient Kempner met was charged with a felony after police pulled him over for a traffic stop and found mushrooms in his car. (His sentence came with mandatory rehab and probation, no jail time, according to Kempner's account.)

Early data

But many cluster headache patients who have benefited from psilocybin remain undaunted.

Over the years, Clusterbusters has pushed for rigorous research into psilocybin's benefits, even offering to fund the studies themselves, said Kempner, also associate professor in the Department of Sociology at Rutgers University, who lives in West Philly and has had migraines since she was a child.

The advocacy is starting to pay off. A 2015 Clusterbusters survey of 500 patients found people reported psilocybin worked as well as or better than most conventional medications, even at low (non-hallucinogenic) doses. "People keep reporting that psychedelics are the most effective treatment they've used, compared to all the other available legal treatments," said Kempner.

A 2022 paper published in the scientific journal Headache tested psilocybin in 16 cluster headache patients using a randomized controlled trial — the gold standard in medical research — in which they received either psilocybin or a placebo. The research showed a "pulse" dosing schedule of psilocybin, similar to what Clusterbusters recommends (three doses, five days apart), appeared to reduce the frequency of attacks.

But the finding wasn't a slam dunk, as the results were not statistically significant — meaning, they could have been due to chance. This isn't a surprise, said Kempner, because only a small number of patients took psilocybin, too few to generate more convincing data. But when the study participants returned for a 2024 paper to repeat the pulse dosing six months later, the frequency of cluster attacks were cut in half — a finding that was statistically significant.

Still, research isn't confirming the "outrageously positive effects" people are reporting from psilocybin, said Kempner. That may reflect the difficulty of testing therapies for cluster headaches, she noted: The pain comes and goes, and many patients may not be willing to take the risk of getting a placebo drug while they're experiencing blinding pain, especially when they could grow the drug being tested at home. "It's such a hard disease to study," she said.

Despite all we still don't know about psilocybin and cluster headache, Kempner remains impressed by the data cluster headache patients have fought to get — and, even more, by how they used that advocacy to form a community.

Another way to serve

Psilocybin doesn't work for everyone with cluster headaches, but the advocacy around it has created a community of patients who can pick each other up when they fall, and offer hope that someday, somehow, they will get relief.

"The drugs themselves, the mushrooms themselves, have knitted together this incredible community of people who support each other," Kempner said. "That's what impresses me."

Now retired from firefighting, Joe McKay has devoted his life to what he considers new types of service.

When cluster headaches took his life away, and psilocybin helped give it back, McKay vowed to serve this new community, fighting to give people with cluster headache access to the medicine that helped him the most.

Even though psilocybin is illegal, McKay doesn't worry about talking to lawmakers or advocating for the right to use it. "For the people in my community, a lot of us, it's psilocybin or suicide," he said. "I shouldn't go to jail because I just want to be pain free." That said, he doesn't like being put in this predicament. "I don't want to be an outlaw, but I am."

To him, this work is an extension of what he did as a firefighter. "I took an oath of office to serve and protect the people. Every single cluster headache attack is a medical emergency. How do you not help?"

©2024 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments