Health Advice

/Health

Mayo Clinic Q&A: Tips for summer water safety

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: We just moved to an area with a lot of opportunities for water recreation and are so excited about our first summer on the water. But we want to make sure everyone stays safe. Can you give us some pointers for water safety?

ANSWER: Nothing beats a day at the lake, river, beach or pool for fun, fitness, fishing and relaxation. ...Read more

Delivering babies is usual for this nurse midwife, but it's far from her whole job

MINNEAPOLIS — Andrea Engdahl remembers the first time she said the words, 25 years ago.

“I want to be a midwife.”

She was pregnant with her first child at the time and exploring her health care options. A nurse midwife, she discovered, was a registered nurse who delivers babies and cares for women from puberty through menopause.

...Read more

How Trump's Medicaid work requirements could affect mental health care

For many people who have a serious mental illness or are recovering from one, trying to get or keep a job may be overwhelming and exhausting.

Finding out that you need a job in order to keep accessing your mental health care can feel insurmountable.

Yet that may soon be the case for nearly half a million Washington residents.

Under a new rule...Read more

Ask the Pediatrician: How reading can help prevent the summer slide

Summer vacation gives your child a much-needed break from school routines, which is important. But, at the same time, it can also result in what educators call the summer slide or "brain drain" — a learning gap that opens when kids spend long periods away from the classroom.

Not only can reading be a fun leisure activity, it can keep your ...Read more

How to talk to family and friends about a head and neck cancer diagnosis

ROCHESTER, Minn. — Talking to loved ones about a recent head and neck cancer diagnosis can be overwhelming. Of course, there is no one “right” or “wrong” way to handle these conversations — or adjusting to your life with cancer. Everyone has their own pace, preferences and relationship patterns. But taking the time to consider your ...Read more

Insurers fight state laws restricting surprise ambulance bills

Nicole Silva’s 4-year-old daughter was headed to a relative’s house near the southern Colorado town of La Jara when a vehicle T-boned the car she was riding in. A cascade of ambulance rides ensued — a ground ambulance to a local hospital, an air ambulance to Denver, and another ground ambulance to Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Silva’s...Read more

World's premier cancer institute faces crippling cuts and chaos

The Trump administration’s broadsides against scientific research have caused unprecedented upheaval at the National Cancer Institute, the storied federal government research hub that has spearheaded advances against the disease for decades.

NCI, which has long benefited from enthusiastic bipartisan support, now faces an exodus of clinicians...Read more

Missouri abortion ban would also restrict transgender care. It's already illegal

For Celeste Michael, the transgender community is being used as a pawn in Missouri’s push to ban abortion.

When the 23-year-old went to vote in Lee’s Summit last November, signs outside her polling place falsely claimed an abortion rights amendment would legalize transgender surgeries for minors. Nearly 52% of voters approved the measure, ...Read more

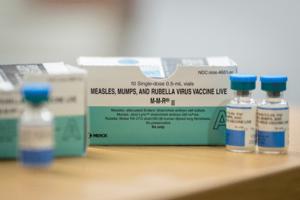

How a Supreme Court win for public health bolstered RFK Jr. and threatens no-cost vaccines

WASHINGTON — Public health advocates won a big case in the Supreme Court on the last day of this year's term, but the victory came with an asterisk.

The decision ended one threat to the no-cost preventive services — from cancer and diabetes screenings to statin drugs and vaccines — used by more than 150 million Americans who have health ...Read more

Dealing with extreme heat is a full-time job for parents of young kids -- and their schools

LOS ANGELES — When Aida Maravilla was on the hunt for a new apartment in 2021, she had one major goal: Find a place with air conditioning.

She learned the hard way that cool air is more than an amenity. When her daughter was an infant she remembers the baby waking up in tears from the heat. Maravilla would soothe her with a wet cloth and ...Read more

Measles cases are on the rise: How is Southern California faring?

Measles cases throughout the U.S. are on the rise — but Southern California is faring better than other states.

Nationally speaking, more cases have been reported halfway through 2025 than any other year since the disease was declared eradicated in the U.S. in 2000.

In California, 17 cases have been reported thus far in 2025. In 2024, the ...Read more

Workplace mental health at risk as key federal agency faces cuts

In Connecticut, construction workers in the Local 478 union who complete addiction treatment are connected with a recovery coach who checks in daily, attends recovery meetings with them, and helps them navigate the return to work for a year.

In Pennsylvania, doctors applying for credentials at Geisinger hospitals are not required to answer ...Read more

Editorial: Golden age for disease: RFK presides over rampant measles

Proving once again that anti-vax quack Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is a threat to public health, confirmed measles cases in the United States have hit a 33-year high.

It’s even worse since it’s been a quarter century since the deadly disease was declared completely eradicated in the country. But no more.

The ...Read more

States brace for reversal of Obamacare coverage gains under Trump's budget bill

Shorter enrollment periods. More paperwork. Higher premiums. The sweeping tax and spending bill pushed by President Donald Trump includes provisions that would not only reshape people’s experience with the Affordable Care Act but, according to some policy analysts, also sharply undermine the gains in health insurance coverage associated with ...Read more

Mayo Clinic Q and A: Signs of overtraining

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I've taken up running again and decided to enter a half-marathon. I know I have to push myself to get ready for the race, but I don't want to overdo it. What should I watch out for as I train?

ANSWER: We're surrounded by warning signs — on the roads, at work, and on packaging and equipment. Your body sends warning signs, too...Read more

South Carolina sees first measles case of 2025, officials say

An Upstate South Carolina resident has the measles, the South Carolina Department of Public Health confirmed Wednesday. It is the first case of the disease in the state since September 2024, the agency said.

The affected resident is not vaccinated and caught the virus during an international trip, according to a press release. They are ...Read more

The hidden costs of caregiving: Crisis goes well beyond financial issues

It’s no secret that the United States ranks near the bottom of high-income countries when it comes to caregiver support policies.

What is less known is the emotional, social and financial toll it takes on the 2 in 5 Americans who identify as family caregivers, according to a recent study conducted by Edward Jones in collaboration with Morning...Read more

Environmental Nutrition: Need help choosing a cereal that fits your needs? Read on

Cold cereals can be anything from a quick and easy breakfast to a comforting midnight snack and many things in between. Cereal was first developed in a sanitarium to aid with digestion. Over the years it transformed into something that was more sugar and less nutrition. Fortunately, the pendulum has swung back a bit. While there are plenty of ...Read more

Eating Well: 5 foods to stock up on in July

While the gourds of fall and the grassy green shoots of spring have their charm, it’s the summer produce that often brings the most joy. July is one of the best times to enjoy a wide variety of fruits and vegetables, and these are some that dietitians recommend stocking up on.

1. Tomatoes

Tomatoes are an excellent example of summer produce ...Read more

Mayo Clinic Q&A: Knee osteoarthritis: When is it time for a joint replacement?

DEAR MAYO CLINIC: I was diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis. When is a knee replacement appropriate?

ANSWER: Osteoarthritis is an extremely common condition affecting over 500 million people worldwide. The knee is the most frequently affected joint. Knee osteoarthritis occurs when protective cartilage in the knee wears down leading to ...Read more

Popular Stories

- Delivering babies is usual for this nurse midwife, but it's far from her whole job

- How Trump's Medicaid work requirements could affect mental health care

- Mayo Clinic Q&A: Tips for summer water safety

- How to talk to family and friends about a head and neck cancer diagnosis

- Eating Well: 5 foods to stock up on in July