What is voluntary sterilization? A health communication expert unpacks how a legacy of forced sterilization shapes doctor-patient conversations today

Published in Health & Fitness

Sterilization is a safe and effective form of permanent birth control used by more than 220 million couples around the world. Despite its prevalence, however, patients seeking sterilization from their doctors often face a surprising number of challenges.

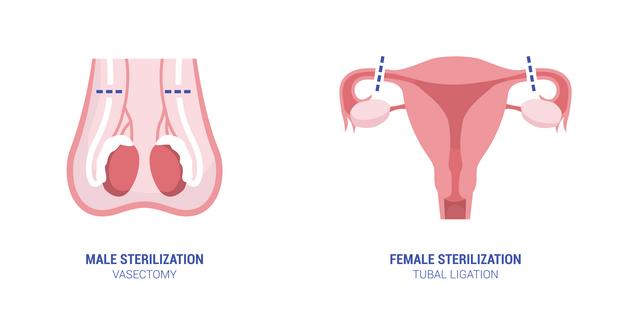

In men, the sterilization process is known as a vasectomy, which involves severing the tubes that carry the supply of sperm to the semen. In women, sterilization involves a procedure called tubal ligation. In this form of permanent birth control, the fallopian tubes are severed – or ligated – preventing eggs produced by the ovaries from traveling through the fallopian tubes to fertilize an egg. Vasectomies and tubal ligations can be reversed in some cases, although success rates vary widely.

A 2018 study found that female sterilization is the No. 1 form of contraception in the U.S., used by nearly 1 in 5 women ages 15 to 49. And a partner’s vasectomy is the fifth leading contraceptive, relied on by 5.6% of women in that age group, after birth control pills, male condoms and intrauterine devices, or IUDs.

I’m a scholar of health communication with expertise in women’s health issues and interactions between patients and doctors. My work explores how patients manage the stigma associated with seeking sterilization and communicate with others about their reproductive decisions. My research also illuminates why patients find talking about sterilization with their doctors so challenging.

Ethical guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend that doctors should respect a female patient’s wishes as a matter of “reproductive justice” when deciding whether to approve their request for voluntary sterilization. The American Urological Association, on the other hand, does not appear to offer ethical guidelines concerning the provision of vasectomy services for male patients.

Yet research has documented that patients seeking sterilization procedures, especially women, are sometimes told that their doctors will not perform the procedure because of the person’s age, number of children or potential risk of regret, among other factors. Providers may also refuse to perform sterilization procedures for other reasons, including fear of legal culpability, backlash from the medical community or conscientious refusal. The latter means that a doctor cannot be compelled to provide a medical service that goes against their best judgment or personal convictions.

This hesitancy to approve sterilization requests reflects the tension over forced sterilization in the past.

Perceptions of sterilization in the U.S. have been marred by a dark history of eugenics, in which racist ideas about who ought to have children have shaped reproductive policies and doctors’ reproductive counseling. And these views have given rise to the term “voluntary” sterilization, meant to contrast with the “involuntary” – or forced – sterilization of earlier decades.

From the late 1800s until the late 1940s, eugenicist movements sought to preserve racial purity by limiting the breeding of people who were considered “unfit” and promoting the proliferation of those who were white and of European descent, from middle or upper classes and considered able-bodied and of sound mind. Widespread federally funded involuntary sterilizations continued in the U.S. until 1979.

In contrast, women who were poor, disabled, immigrant, Black, Hispanic or Indigenous who sought to have children often faced coercive or forced sterilization, sometimes without their consent or knowledge.

When women who were considered “desirable” sought to limit their family size or forgo having children altogether through voluntary sterilization, they were sometimes denied the procedure. That trend continues today despite ethical guidelines recommending otherwise, since doctors cannot be compelled to perform medical procedures they find objectionable. Furthermore, sterilization services, like other reproductive health services, are often not offered at religiously affiliated hospitals.

These cultural views contribute to disparities in access to sterilization that persist today.

In 1979, federal legislation went into effect to halt Medicaid-funded involuntary sterilizations and to limit Medicaid-funded sterilization services to any person of sound mind over the age of 21. But ironically, this legislation – which was designed to prohibit involuntary sterilization – now restricts some patients who are seeking sterilization.

Laws vary widely from state to state, meaning that where you live dictates how accessible voluntary sterilization is to you. For example, in Kansas, the most legally restrictive U.S. state, individual doctors are not held accountable for refusing to perform sterilizations, even if they are medically necessary. In addition, medical facilities and individual doctors can also legally refuse to provide information or refer patients elsewhere to procure the procedure.

In contrast, in California – a state that has progressive reproductive health care rights – a right to voluntary sterilization is enshrined in law. This means that patients cannot be discriminated against because of factors like age or the number of children they have. Yet forced sterilization is still legal in California for patients with developmental disabilities who are under conservatorship.

This patchwork of policies across U.S. states creates room for bias in the patient counseling process. Today, when Black and Native American women seek sterilization voluntarily, they are still more than twice as likely as non-Hispanic white women to be approved for the procedure by their doctors. In my view, this shows that decisions about who can be sterilized are still inherently attached to racial bias as well as gender and class bias.

In the aftermath of the fall of Roe v. Wade, which overturned nearly 50 years of abortion rights, people living in at least 13 U.S. states may now be in a double bind: unable to find a doctor who will grant them the permanent sterilization they desire to prevent an unwanted pregnancy, and also unable to access an abortion should a pregnancy occur.

With abortion access reduced in many states after the Supreme Court’s ruling overturning Roe v. Wade, it’s more important than ever for patients to be able to discuss voluntary sterilization freely with their medical providers.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It was written by: Elizabeth Hintz, University of Connecticut. Like this article? subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more:

Forced sterilization policies in the US targeted minorities and those with disabilities – and lasted into the 21st century

Forced sterilization programs in California once harmed thousands – particularly Latinas

Elizabeth Hintz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments