What's in a surname? What last names reveal about social mobility.

Published in Slideshow World

Subscribe

What's in a surname? What last names reveal about social mobility.

Americans pride themselves in living in the "land of opportunity." Rags-to-riches stories continue to appeal because they embody the idea that people can be free from social constraints and class systems. People hope that anyone—no matter where they're from—can achieve the American Dream through initiative and hard work.

However, great wealth can hinge on something as simple as a name.Surnames examined academic research to see how a person's name could determine their social status and ability to become successful.

Many economists have researched intergenerational social mobility through different lenses.

World Bank researcherRoy van der Weide and a team of economists studied social mobility in terms of educational achievement being the key to future success. They found that people in developing countries don't have the same opportunities for education as high-income nations, so the opportunity to move to different social strata is also lower.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development studied social mobility through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic, finding that economically disadvantaged people had trouble accessing educational resources. Inflation and employment recovery also created more challenges, keeping lower-income workers from advancement.

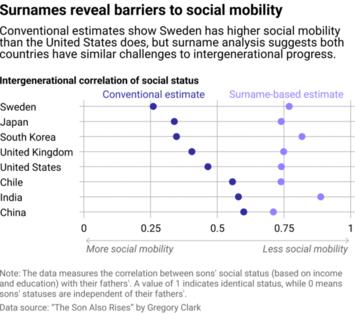

Many of these findings do not come as a surprise, but economist Gregory Clark's research published in his book, "The Son Also Rises" stands out because it looks at something people are born with—a surname—rather than a situation people are born into. Clark suggests that in America and elsewhere, vast changes in social mobility are much lower than commonly believed, dashing the notion that in America, most people can bootstrap their way to success.

Visit thestacker.com for similar lists and stories.

Across the world, surnames determine social mobility potential

Clark looked at centuries of census and genealogical data, which allowed him to see just how slowly it could take for people to move across social strata.

In England, for example, he looked at unusual surnames dating back to the Norman invasion, which began in 1066. Tracing these surnames by where they went to school and their occupations, Clark surprisinglydiscovered very little change in social mobility—not just for a few generations, but for the last 1,000 years.

Clark found that the elite generally remain elite—for example, Norman-sounding names are still overrepresented at Oxford and Cambridge, even as these schools' admission criteria have become more standardized and accessible to more of the population. Clark even found that surnames of wealthy people also increased their descendants' probability of being wealthy, living longer, and choosing to become doctors or lawyers.

While this may not be surprising for a historically rigid society like the United Kingdom's, when Clark applied it to other countries, he got similar results. Sweden has a great deal of government assistance programs to help lower-income families move to higher social levels. Yet, Clark found that Swedes with surnames of elite statusconsistently maintained that status in the form of wealth, education, and occupations over the course of 200 years.

Even communist countries like China also have surprisingly low rates of social mobility. While the 1949 revolution pushed out the ruling elite class, causing some social mobility in the country, Communist party leadership became the new elite, continuing the cycle in a similar manner.

Even with the rose-colored glasses of the American Dream, the U.S. is in the middle of the pack when it comes to social mobility. With the U.S., a nation of immigrants, Clark took the approach of looking at names by ethnicity, suggesting that racial inequalities persist for a longer period than some way have initially thought.

But other factors also increase social mobility prospects

Other researchers have used different factors to explore social mobility rates across generations. A 2019 study by Xi Song at the University of Pennsylvania and other collaborators suggests that social mobility was rising before World War II, with industrialization driving change as new types of higher-paying manufacturing jobs lured workers away from farms to cities. For those born after 1940, however, social mobility hasn't changed much across generations.

Raj Chetty and other researchers from Harvard University and the University of California, Berkeley, found that geography plays a significant role in the probability of achieving upward mobility in the U.S. Their 2014 paper, which examined decades of data on millions of U.S. residents, discovered different regions of the country had larger disparities depending on the level of economic opportunity. Those in the Southeastern United States have less chance of achieving a higher social mobility than those in the Mountain West. In Charlotte, North Carolina, the likelihood of a person moving from the bottom to the top quintile of income was 4.4%, while in San Jose, they had a nearly 13% chance of making the jump. In examining surnames, the researchers found a smaller relationship between surnames and social mobility than Clark.

If a surname holds the key to determining one's social status at birth, it's more difficult to change the status quo. A study on surnames in Modena, Italy's local newspapers, published in a 2024 issue of the journal Social Indicators Research, found that those with higher social status made the news more often and had more social clout. In the U.S., this is evident in the political realm, with family dynasties like the Kennedys and Bushes maintaining high social status for several generations.

While one's name may be indicative of social status, governments could play a role in increasing social mobility for those who aren't born to the right family. In research published in 2022, Brookings Institution found that the opportunity for upward wealth mobility decreases with age, so policies should take into account how to create more upward mobility throughout a person's life. Programs to improve homeownership rates, encourage saving, and promote retirement planning can help people build wealth in a way that could propel them upward, regardless of their family lineage.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Surnames and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Comments