David Gilmour on nepo babies, deluded baby boomers and giving up the fight over Pink Floyd

Published in Entertainment News

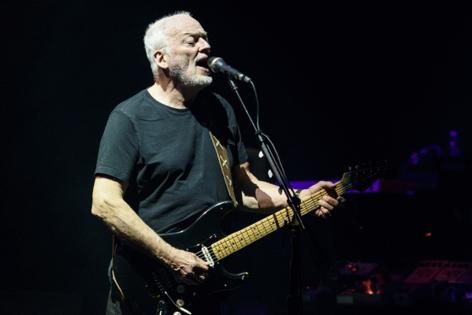

LOS ANGELES — It's dusk inside an empty Hollywood Bowl as David Gilmour peers out from the stage and delivers his song "Dark and Velvet Nights" to no one in particular. A strutting psych-blues jam with visions of "great cities that toppled and drowned," it's a highlight from the Pink Floyd veteran's strong new solo album, "Luck and Strange" — and one of the latter-day cuts his fans will politely nod their heads to a few hours from now between beloved oldies such as "Wish You Were Here" and "Comfortably Numb."

At 78, Gilmour has been at this long enough to know what his audience wants, which is as much of Pink Floyd's '70s-era songbook as he's willing to play. Not that he especially cares: "When I'm working, I don't consider an audience member's views because that's the death of art, if you ask me," he says after sound check at the Bowl before the second of three gigs there last week. "I'm sorry if it's arrogant to call what I do art, but I'll stick with it." For him, performing his music is its own reward — one reason he sings at close to full power, his voice brawny yet lithe, as his live band test-runs a few tunes behind him.

Gilmour's tour behind "Luck and Strange" — his first studio album and his first road show in nearly a decade — is limited in terms of its itinerary, with dates in only four cities. But in each he's playing multi-night engagements: After stops in Rome, London and Los Angeles (where he also played Inglewood's newly opened Intuit Dome), he opened a five-show run Monday night at New York's Madison Square Garden.

The bookings are an indication of Gilmour's enduring popularity, even as his relationship with Pink Floyd's Roger Waters has hit an all-time low. Last year, after his wife and writing partner, Polly Samson, tweeted that Waters was a "Putin apologist and a lying, thieving, hypocritical, tax-avoiding, lip-synching, misogynistic, sick-with-envy megalomaniac," Gilmour wrote in a follow-up post, "Every word demonstrably true." For a while there, relations between the ex-bandmates seemed at risk of scotching a lucrative deal to sell Pink Floyd's catalog — a deal that eventually went through this year when the band handed over the rights to its recorded work to Sony Music for a reported $400 million. (Pink Floyd's most recent studio album, "The Endless River," came out in 2014, three decades after Waters' departure and six years after the death of keyboardist Richard Wright.)

Seated on a couch backstage at the Bowl, his black pants matching his black T-shirt, Gilmour says he has little interest in addressing the drama with Waters. His thoughts are consumed, he says, by "Luck and Strange," for which he recruited a producer, Charlie Andrew, with no deep affinity for Pink Floyd's classic material. "It was refreshing," he says of the experience with Andrew, who's best known for his work with the British indie-rock band Alt-J. In addition to his wife, who wrote the album's lyrics, Gilmour enlisted his 22-year-old daughter, Romany, to sing and play harp on the LP; there's also a track constructed around an old recording of Wright from 2007. (Pink Floyd's remaining founding member is drummer Nick Mason.) The album is handsome and searching and muscular, and after our talk Gilmour plays most of it onstage at the Bowl while throwing a few familiar bones to the capacity crowd.

Q: What's the hardest song in your set to sing?

A: F—, I don't know. "Coming Back to Life" starts more or less a cappella, so it's got to be spot-on. "Time" is quite high for me these days. "A Great Day for Freedom" is pretty exposed. Obviously, we've got other parts going on — harmonies and so forth. But no lip syncing.

Q: Do you use a prompter?

A: Yeah. I never used one until the last tour I did, in 2015 and 2016. I never needed to. Of course, the minute you start using one … Did you see at sound check? The guy hadn't lined it up from the beginning of the song, and my mind went blank. In the old days, you're there strumming a chord, everyone's playing something, you walk up to the mic and it just comes out. It always did for me. There was a line in "Shine On You Crazy Diamond" that always got me — I used to have those couple of lines on a piece of paper on the stage in front of me. Polly eventually said, "God, just have [a prompter] — give yourself the security." I think I could do without it, but it would take quite a while to be prepared.

Q: To wean yourself from that security.

A: Exactly. And I don't think I want to do that. So I'll contend with this particular trick of the trade.

Q: Your daughter Romany appears on "Luck and Strange," and now she's touring in your band. I wondered if you're familiar with the term "nepo baby."

A: I know all about nepo babies, and I'm entirely in agreement with the sentiment that it's a bad thing to approach. But I was mucking about with this song in my studio at home — this song by the Montgolfier Brothers, "Between Two Points" — and the sentiments of the lyrics just were not working for me. I'm this big, strong, tough person, and this was a very fragile sort of thing. Polly said, "Why don't you try someone else? Maybe try Romany singing it." So I said to Rom, "Come on, have a quick go at this." She said, "Oh, Dad, I've got an essay to write." "Gimme half an hour." "Ugh, OK." She came in the studio in my barn at home, she sang it once, and that's 90% of the vocal you hear. That's not nepo baby — that's f— earned.

Q: Last time you played the Bowl, in 2016, David Crosby joined you for a few songs. What was the initial seed of your long friendship?

A: Graham Nash, really. I knew Nash a little bit in in London when he was still in the Hollies. In fact, he was in one of the studios and we were in another studio the night that he flounced out. I used to play backgammon in the lobby there with one or two of those guys. Anyway, I'd go and see [Crosby, Stills & Nash's] shows and say hi, and I became very friendly with David. He'd come over to the house, and we went on holiday together, boating in the Mediterranean. I was very fond of him.

Q: Did his passing last year come as a shock?

A: His dying, I would call it.

Q: What's the distinction?

A: I hate the word "passing" — "passing away." Why can't people just call things as they are?

Q: What was it like to be the heartthrob in Pink Floyd?

A: I have no idea how to answer that. Maybe you should ask Roger that question — I mean about me, obviously [laughs].

Q: I'm curious because you clearly had a strong look. Yet Pink Floyd didn't ever seem to be selling sex.

A: No.

Q: Which made it different from other bands of that era.

A: I wouldn't say all other bands. I think our audiences were largely male, and though I don't count myself in the nomenclature of prog — hate that word — I would think something in the audiences might have been similar.

Q: What still excites you about the guitar?

A: I just want it to give birth to new tunes. The actual playing and melodies and stuff, they're up here [points to head] and you just transfer it onto the strings. But I want an instrument to give me the start of a song. And, often, getting discomfited slightly helps that process along. I'm a really rotten piano player, but I've written quite a few songs which I think are pretty good on the piano.

Q: Being bad helped you?

A: It's the limitations. When you get a guitar and it's got a different tuning, you find something new. The comfort zone can be too comfortable.

Q: Does that apply to the conveniences of modern recording technology?

A: That gets rid of the obstacles in the way of doing things you get in your head. But yes, it's different from how you develop things in the framework of a band that's been working together and knows each other telepathically from 50 years ago. How does one put this delicately? The reverence that people have around me means that the equality of a band that comes up out of school together — can shout at each other and even punch each other, then the next day you're back and everything's fine — you can't replicate that. That's probably why what we used to know as supergroups came along. Equality is hard to refind.

Q: As a world-famous rock star, you mean.

A: Yeah.

Q: You ever find that your audience is too reverent?

A: That I can't really tell. But I mean, all the way through one's life and career, you do this thing of going onstage and coming off at the end of a gig and going, God, that was s—, and then people come in and say, "God, that was great!" You think, You f— a—hole, what do you know?

Q: The new album's title track ponders the optimism of a postwar generation that saw itself as ushering in a golden age. Maybe I'm just hardwired to say this as a Gen X-er, but it's been exasperating to see that optimism harden among some boomers into a kind of deluded self-regard.

A: I agree. The boomer postwar thing — there was some lovely stuff, and it was an innocent age, but there was a f— of a lot that was not right. If you examine the political beliefs, racism, misogyny, all the things — they're all there. There were people trying their best to move forward — that's the thing I like about it — but a lot of them were f— it up as well.

Q: Recently we've seen a number of culturally prominent boomers take a variety of reactionary stances : your old bandmate Roger, of course, but also Eric Clapton and Van Morrison. Why haven't you drifted to the right?

A: I'm just not like that. I'm horrified by the division and the polarization of this world we're in today. It's the most dangerous moment — worse than the Bay of Pigs. There's no middle left. They're all way out there throwing brickbats at each other.

Q: In your view, you're in the middle.

A: I am, yeah. I used to describe myself quite happily as left of center, and I still think that I'm in the same place. But this spectrum of left and right is such a weird thing to get one's head around these days. The left goes so far around on the spectrum that it meets the far, far right at the back somewhere. I'm staggered at the stupidity of people who bandy around dangerous words without having looked them up in the dictionary.

Q: Such as?

A: I'm not going to give you an example right now. Sorry. I'm a pop musician, and I'm not wanting to go off into a major discussion on all these things at this moment.

Q: Thanks for your time.

A: Hope you like this album better than "The Endless River."

Q: I went back and read my review of that record. It was a little snotty.

A: I'll tell you: When we did that album, there was a thing that Andy Jackson, our engineer, had put together called "The Big Spliff" — a collection of all these bits and pieces of jams [from the sessions for 1994's "The Division Bell"] that was out there on bootlegs. A lot of fans wanted this stuff that we'd done in that time, and we thought we'd give it to them. My mistake, I suppose, was in being bullied by the record company to have it out as a properly paid-for Pink Floyd record. It should have been clear what it was — it was never intended to be the follow-up to "The Division Bell." But, you know, it's never too late to get caught in one of these traps again.

Q: Well, to that point: You're not worried that the sale of Pink Floyd's catalog might lead to other instances where the music is presented in a way you don't like?

A: No.

Q: Why not?

A: It's history — it's all past. This stuff is for future generations. I'm an old person. I've spent the last 40-odd years trying to fight the good fight against the forces of indolence and greed to do the best with our stuff that you can do. And I've given that fight up now. I've got my advance — because, you know, it's not fresh new money or anything like that. It's an advance against what I would have earned over the next few years anyway. But the arguments and fighting and idiocies that have been going on for the last 40 years between these four disparate groups of people and their managers and whatever — it's lovely to say goodbye to. And I haven't sold the publishing rights.

Q: Why hold onto those?

A: That's a very, very different issue. You have to have an agreement about synchronization licenses and all that sort of stuff. [Sony] bought the records, the recordings, and can do what they want. But if it comes on an advert, I'm not gonna give a shit. I'm just not going to. There are all sorts of things that are just as distasteful as that.

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments