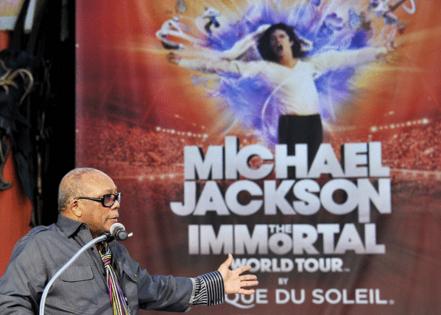

Quincy Jones, legendary composer who shaped Michael Jackson's solo career, has died

Published in Entertainment News

LOS ANGELES — Quincy Jones, who expanded the American songbook as a musician, composer and producer and shaped some of the biggest stars and most memorable songs in the second half of the 20th century, has died at his home in Bel-Air.

Widely considered one of the most influential forces in modern American music, Jones died Sunday surrounded by his children, siblings and close family, according to his publicist Arnold Robinson. He was 91. No cause of death was disclosed.

“[A]lthough this is an incredible loss for our family, we celebrate the great life that he lived and know there will never be another like him,” Jones’ family said in a statement to The Times. “He is truly one of a kind and we will miss him dearly; we take comfort and immense pride in knowing that the love and joy, that were the essence of his being, was shared with the world through all that he created. Through his music and his boundless love, Quincy Jones’ heart will beat for eternity.”

The arc of Jones’ long career stretched from smoky jazz clubs, where he collaborated with innovators such as Miles Davis, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, to his Los Angeles power base, where, like a titan, he watched over his musical empire from a mansion atop Bel-Air.

During his career, Jones helped mold Michael Jackson into a mega-star by producing a trilogy of albums that made the pop singer arguably the best-known musician in the world, raised tens of millions for Ethiopian famine victims by producing the bestselling song “We Are the World” and won 28 Grammy awards, more than any artist aside Beyonce and George Solti.

If some stars reached a career cruising altitude where they were identified by just one name — Prince, Madonna, Sting — Jones boiled it down to a single letter: Q.

Harvard historian and literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. said he viewed Jones’ influence and career milestones as being on par with American innovators and big thinkers like Henry Ford, Thomas Edison and Bill Gates.

“We’re talking about the people who define an era in the broadest possible way,” Gates told Smithsonian Magazine in 2008. “Quincy has a lifeline into the collective consciousness of the American public.”

Oprah Winfrey, who worked with Jones when he helped produce and score the music for “The Color Purple,” described him as being a force of nature, unlike anything she’d encountered.

“Quincy Jones on a bad day does more than most people do in a lifetime,” she said in “The Complete Quincy Jones: My Journey and Passions.”

The late Miles Davis put it another way: “Certain paperboys can go in any yard with any dog and they won’t get bit. He just has it.”

When he was young and amid the legends of the day, Jones said he would “sit down, shut up and listen,” silently absorbing lessons he realized he couldn’t possibly get anywhere else. But fame and success ultimately released any reluctance to speak out, and seemed to loosen his ego as well.

Asked by The Times in 2011 to compare himself to Kanye West (now kown as Ye), Jones seemed indignant.

“Did [West] write for a symphony orchestra? Does he write for a jazz orchestra? Come on, man ... I’m not putting him down or making a judgment or anything, but we come from two different sides of the planet.”

In testament to the respect Jones commanded, when Barack Obama was exploring a presidential bid, one of his first stops in Southern California was the producer’s Bel-Air estate.

Taking in the home’s king-of-the-universe views, Obama listened while Jones told stories of jamming with legends like Gillespie or the surge of power he felt working the soundboard as one mega-star after another stepped forward to sing a verse for “We Are the World.”

Quincy Delight Jones Jr. was born March 14, 1933, in Chicago. His father, Quincy Jones Sr., was a semi professional baseball player and a carpenter. His mother, Sarah Frances, was a bank officer and an apartment manager. His younger brother, Lloyd, died in 1998.

As a youth, Jones was exposed to Black roots and religious music and early jazz piano. His mother was an avid singer of spirituals and a next-door neighbor, Lucy Jackson, helped Jones learn to tap out boogie-woogie on the keyboard.

When he was 10, Jones’ mother was committed to a mental institution. The impact was profound and Jones said he was left with painful memories of the trips to the psychiatric hospital, unsure exactly why his mother couldn’t come home with him.

“They took her away in a straitjacket, man,” he said in a 2009 interview with The Times. “For me, that was the end of what mother meant.”

With his mother institutionalized, Jones said, he began to run the streets. It was a tough, beaten-down neighborhood on the south side of Chicago and gangsters controlled every block. One day when Jones was walking home, a group of street toughs pinned him to a fence, plunged a knife blade into one of his hands and stabbed him in the temple with an ice pick.

That helped convince Jones’ father, who had divorced and remarried, that it was time to get out of Chicago.

In search of a better job and a safer environment, Jones’ father moved his newly blended family to Bremer, Washington, in 1943 and found work at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. When the war ended, the family moved to Seattle.

The upheaval and family turbulence shaped Jones. “If I had a good family,” he once joked, “I might have been a terrible musician.”

When he was 14, he befriended a teenager named Ray Charles. The friendship, which lasted a lifetime, opened a new world for Jones.

In Charles, Jones found an emerging prodigy, a musician who played a blend of blues, gospel and R&B he’d never heard. The two started playing together and Charles — blind since he was 7 — urged Jones to pursue arranging and composing.

“I met Ray Charles at 14 and he was 16,” Jones recalled “But he was like a hundred years older than me.”

After high school, Jones attended Seattle University and earned a scholarship to what’s now the Berklee College of Music in Boston. In the early ’50s he joined Lionel Hampton’s big band as a trumpeter and arranger and later toured South America and the Middle East with Gillespie’s big band.

Jones’ visibility escalated and, barely into his mid-20s, he was soon arranging and recording for Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Count Basie, Duke Ellington and, of course, Charles.

In the late ’50s, Jones relocated to Paris, where he studied composition with the highly regarded teacher Nadia Boulanger and composer Olivier Messiaen. But a European tour leading his own big band in the early ’60s ran into financial problems and came to an unceremonious end.

“We had the best jazz band on the planet,” Jones told Musician magazine, ”and yet we were literally starving. That’s when I discovered that there was music, and there was the music business.”

Another door opened when Mercury Records offered Jones a position as musical director of the company’s New York division. In 1964, he was promoted to vice president of Mercury Records, the first Black person to hold an executive position at a major U.S. record company.

Jones’ successes continued. In the mid-’60s, he produced four million-selling singles and 10 Top 40 hits for Lesley Gore, including “It’s My Party.” He also arranged Frank Sinatra’s iconic “Fly Me to the Moon.”

In 1964, he agreed to compose the music for Sidney Lumet’s “The Pawnbroker.” It was the first of more than 30 films that Jones would score, a list that included “The Deadly Affair,” “In the Heat of the Night,” “Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice,” “They Call Me Mr. Tibbs!” and “The Getaway.”

While the jobs came quickly, the undertow of racism in the industry was always there, tugging at him.

When Jones was asked to write the soundtrack for “In Cold Blood,” he said Truman Capote, who wrote the bestselling book the film was based on, tried to block him from working on the film.

“He said, ‘I just don’t understand why you want a colored man’s music in a film with no negros,’” Jones told the San Francisco Chronicle in a 2008 interview. “I knew it was going to be hard for a Black guy to break into movies.”

The musical score for “In Cold Blood,” though, earned him an Academy Award nomination in 1967, the first of seven times he was nominated.

Jones was equally productive for television, composing the theme music for “Sanford and Son,” “The Bill Cosby Show,” “Banacek” and “Ironside.”

His busy schedule also included the founding of his own company, Qwest Productions, and stints providing arrangements for Peggy Lee, Sarah Vaughan, Billy Eckstine and Ella Fitzgerald, Sinatra and his own bands.

After producing the soundtrack for the 1978 film “The Wiz” — which featured Diana Ross and Michael Jackson — Jones was approached by Jackson, who wondered if he would produce his next album.

Jackson’s record label initially stood in the way, worried that Jones was a jazz guy. Jackson pushed back, insisting he wanted to work with Jones.

“Everybody said, ‘You can’t make Michael any bigger that he was in the Jackson 5,’” Jones recalled. “I said, ‘We’ll see.’”

The album, “Off the Wall,” was a critical success, but the follow-up, “Thriller,” released in 1982, became the bestselling album of all time and earned eight Grammy awards. Suddenly, Jackson’s career was kicked into the stratosphere and Jones was regarded as the high priest of pop music.

Five years later, Jackson released “Bad,” the third and final collaboration between the two. It yielded five No. 1 hits.

Jackson, Jones said, was the hardest-working performer he’d ever seen. To fully harness the emotional might that Jackson seemed to possess, Jones said he transformed the recording studio into a concert stage by dimming the lights and urging Jackson to dance while he recorded, as if an entire audience were bearing witness. Decades later, Jones was awarded $9.4 million after a Los Angeles jury determined he’d been shortchanged millions in royalties by Jackson’s estate.

A year later, following the 1985 American Music Awards, Jones assembled a star-studded team of musicians, from Ross to Bruce Springsteen, to record “We Are the World.” The song became one of the bestselling singles of all time and raised nearly $70 million to assist victims of the famine in Ethiopia.

But the workload, the stress and the weight of a crumbling marriage had taken a toll and Jones broke.

He postponed all ongoing projects, canceled his scheduled appearances and flew to Tahiti. Alone.

“I stayed for 31 days,” he told The Times in 1989. “It was the most heavy 31 days of my life. I went all the way down. I just wandered from island to island. I was really in trouble.”

As he put the pieces back together, Jones said he felt oddly renewed, as if he’d undergone a spiritual cleansing. “Sometimes you need God to just slap you and say, ‘Let’s take a look and see what’s going on here.’”

Back in L.A., his career resumed briskly. He formed Quincy Jones Entertainment, a partnership with Time Warner, produced NBC’s ‘Fresh Prince of Bel Air,” staged an inauguration concert for President Bill Clinton and began recording “The Q Series,” an ambitious anthology of Black American music. He also formed Qwest Broadcasting, which then was the largest minority-owned broadcasting company in the U.S.

In 1996, he produced the 68th annual Academy Awards telecast. Three years later, U2 lead singer Bono, singer-songwriter Bob Geldof and Jones met with Pope John Paul II as part of an effort to erase the debt load shouldered by third world nations. And in 2008, he was named an artistic adviser to the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, a post some urged him to reject in protest over China’s dismal human rights records.

The awards and honors bestowed on Jones were nearly mind-bending. He was nominated for a Grammy 80 times, winning 28 times. He received eight Academy Award nominations. He was the first musician whom France honored as both Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur. He was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and he received Kennedy Center Honors.

Jones’ Quincy Jones Foundation distributed millions of dollars in L.A. and abroad to advance humanitarian causes and encourage arts education. Quincy Jones Elementary School in South L.A. was named in his honor. When he attended the ribbon-cutting in 2011, he said it brought back memories of when he first arrived in L.A.

Late in life, Jones reflected on his mortality, telling The Times that he had deleted the names of 188 friends and associates from his iPhone in a single year. All dead.

“You start out playing in bands and doing duets,” he said. “And then you worry that in the end it’s all going to be a solo.”

Jones was married three times, the longest to actress Peggy Lipton. He is survived by seven children, including actor Rashida Jones.

____

Former Times jazz critic Don Heckman contributed to this story prior to his death in 2020. Marble is a former Times editor.

©2024 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments