Harry Partch's priceless musical instruments return to San Diego after 33-year odyssey

Published in Entertainment News

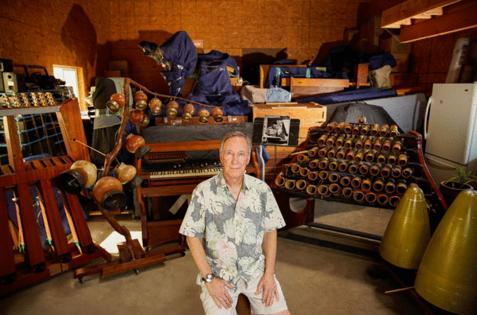

SAN DIEGO — A treasure trove of unique musical instruments invented and built by pioneering composer Harry Partch between 1930 and 1972 were quietly returned to San Diego last week, ending a 33-year-long transcontinental odyssey.

“I am beyond exhausted, but my heart is full,” said longtime Partch champion Jon Szanto, who was pivotal in bringing these ear- and eye-popping instruments back home. “Second only to my beloved family, this is the most important thing I’ve done in my life.”

The singular instruments’ return is the latest chapter in the legacy of Oakland native Partch, who was born in 1901 and began writing his own music at the age of 14. A visionary composer whose high-profile admirers include Paul Simon, Tom Waits and composer Lou Harrison, Partch was a devoted hobo early in his adult life and a tireless innovator throughout it.

He moved to Encinitas in 1967 before settling in Normal Heights, a San Diego community whose name could not have been more at odds with Partch’s cutting-edge, proudly left-of-center approach to life and music. He died in 1974 at the age of 73. His impact is still being felt.

A lifelong maverick and proud iconoclast, Partch rejected Western music’s conventional 12-tone octave and “the tyranny of the piano scale,” which he resolutely dismissed as “wholly irrational — an oppressive lid on musical expression.”

After creating an expansive, 43-tone scale, he designed and built an increasingly exotic array of unique musical instruments to bring the microtonal music he heard in his head to life.

The more than three-dozen instruments he created — all designed and painstakingly handcrafted by Partch — include the 72-string Kithara II, which is nearly 7 feet tall, and the Bass Marimba, which is 7 1/2 feet long and weighs about 600 pounds. Among the unorthodox materials he used to create his instruments were brass artillery shells, bamboo, hubcaps and the carefully calibrated, cut-off tops of 12-gallon industrial Pyrex chemical bottles.

The instruments’ coast-to-coast trek began in early 1991, when they were moved from their longtime home at San Diego State University to, in succession, the music departments at universities in New York, New Jersey and Washington, where they sat in storage since 2019.

After years of effort by Szanto to find a permanent home here for the instruments, they were carefully packed into a 52-foot-long semitrailer and arrived Oct. 2 at an undisclosed San Diego location. It took Szanto and about 15 colleagues and volunteers three hours to unload and move all the instruments into their new home.

The return of the instruments is an overdue full-circle moment. It comes just a few months after the July 31 death of former San Diego State University music professor Danlee Mitchell, who was the music director for San Diego’s Harry Partch Ensemble from its inception in 1970 until 1986, when the nonprofit group stopped touring due to rising costs. Five years later, Mitchell indefinitely loaned the instruments to a university in New York.

‘This is wonderful!’

News of the instruments’ return to San Diego has drawn immense excitement from members of the music community, near and far.

“I was a student when I first saw and heard the Partch instruments — in photos and on recordings — and I was stunned not only by their sounds but by their beauty,” said UC San Diego music professor Steven Schick, one of the nation’s most acclaimed percussion soloists. “Having these instruments in San Diego again will return them to their proper home and will create a vital center here for the continuation of Partch’s legacy.”

“This is wonderful news!” said violin star Leila Josefowicz, who will be the soloist at the San Diego Symphony’s Nov. 16 and 17 concerts at Jacobs Music Center. “Harry Partch was one of the most exciting, creative and experimental artists in our field — a composer, an inventor, an instrument builder, a philosopher … It is so important more people know about his music, his incredible inventiveness in our art form, and his amazing instruments.”

Those sentiments are shared by veteran Harry Partch Ensemble member Francis Thumm and by retired San Diego Symphony percussionist Jim Plank, the latter of whom will be inducted into the San Diego Music Hall of Fame on Nov. 8.

“There’s a genuine feeling of relief and excitement just knowing Harry’s instruments are here again. It’s like welcoming old friends back that have been gone far too long,” said Thumm.

“These instruments,” said Plank, “are integral to Harry’s music and to his position in the pantheon of great American composers. His music cannot be heard except through these instruments, because they are like no other Western instruments in existence. I’m absolutely thrilled they are finally coming back to San Diego. And it’s a credit to Jon Szanto for devoting years to finding a way to get these instruments back here where they belong.”

Partch earned a National Institute of Arts and Letters honor in 1966 and received commissions and grants from the Guggenheim and Carnegie foundations. His life and work have been documented in books and film. Partch independently released 15 albums of his music before he was signed by Columbia Masterworks, one of the classical music world’s most prestigious record labels.

His two albums for Columbia, 1969’s “The World of Harry Partch” and 1971’s “Delusion of the Fury (A Ritual of Dream and Delusion),” earned him international praise, inspiring fellow composers Lou Harrison and György Ligeti, along with former San Diego singer-songwriter Tom Waits, a 2011 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee.

“He definitely was an influence on me — when you hear Harry’s music, you can’t help but incorporate it,” Waits said in a 2004 interview with The San Diego Union-Tribune. “He designed his own instruments, which are awesome to behold, and system of notation. And he incorporated Chinese poetry with the things he read on passing water towers when he was a railroad bum. He invented himself and his music.”

Partch’s influence also extends to Paul Simon, an avowed fan of what he has described as Partch’s “strange, often eerily beautiful, landscape of sound.”

Simon recorded a song for his 2016 album, “Stranger to Stranger,” that features five of Partch’s colorfully named instruments: Chromelodeon, Cloud Chamber Bowls, Kithara, Marimba Eroica and Sonic Canons.

Some of the Partch instruments were also featured on Ha; Willner’s all-star 1992 album, “Weird Nightmare: Meditations on Mingus.” It featured San Diego’s Thumm, jazz greats Henry Threadgill and Bill Frisell, rapper Chuck D. of Public Enemy, Elvis Costello, Keith Richards and Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones, and others, including former San Diego drummer and classically trained percussionist Michael Blair, a former Tom Waits band member.

“I was fortunate to visit Danlee MItchell when the totally unique Partch instruments were stored at San Diego State,” Blair said via email from his home in Stockholm.

“I was a ‘kid in a candy store’ playing all the instruments and feeling the love and concern necessary to keep the Partch legacy alive… That Danlee’s hard-earned legacy brings the sounds and possibilities of Partch’s work back ‘home’ makes good sense.”

Passing the torch

Szanto became the curator and archivist for Partch’s estate in 1996. That is the same year he launched corporealmeadows.com, a dizzyingly comprehensive website for all things Partch. He headed San Diego’s nonprofit Harry Partch Foundation, which he hopes to obtain funding soon to reactivate, and has produced and overseen the releases of several posthumous Partch albums.

“Jon has made it his mission to preserve the legacy of Harry and all the physical aspects of Harry’s music,” Plank said. “Danlee Mitchell’s passing was, symbolically, the passing of the torch — and, by extension, the instruments and the history of Partch’s music — to Jon to get the instruments back here, safely store them, and get them ready for the future.”

Szanto, like Plank, spent decades as a percussionist in the San Diego Symphony and he joined the Harry Partch Ensemble in 1971. Alongside Thumm, Randy Hoffman and other devoted members, Szanto did three West Coast tours with the ensemble. He was also on board for its concerts in New York, Philadelphia and the German cities of Cologne and Berlin, where the 1980 live album “The Bewitched: A Ballet Satire” was recorded.

The instruments first arrived in San Diego in 1967 for a brief stay at UC San Diego in La Jolla, where Partch taught a semester-long seminar as a Regent’s Lecturer. After some UCSD concerts in May 1968, Partch and the instruments moved to Los Angeles for a major production of “Delusion of the Fury” at UCLA’s Royce Hall in early 1969.

Had things gone better at UCSD, it is possible the instruments might have found a home at the La Jolla campus. But that’s not how things transpired.

“Harry was underwhelmed by how the UCSD music department handled things during his semester there. After that, he didn’t want to have anything to do with them,” Szanto said.

“Until Danlee offered to have the instruments housed in the SDSU music department, Harry never had the support of an academic institution for more than a year or two. They always gave him the bum’s rush. Danlee told me that at one point, when Partch was tired of it all, he told Danlee: ‘Put everything in a truck, take it down to the beach in Del Mar, and have the biggest bonfire you can have.’ ”

Later in 1968, Partch and his instruments returned to San Diego. He died six years later. The instruments remained here for 22 years, under Mitchell’s careful watch, in a large room in the SDSU music building where the Partch Ensemble rehearsed for concerts here and national and international concert tours.

Szanto worked closely through the years with Mitchell, who founded SDSU’s percussion department in 1964. Mitchell was Partch’s most trusted confidante and collaborator and upon the composer’s death, Mitchell was designated as the sole recipient of his instruments and music. Szanto, in turn, was Mitchell’s most trusted confidante.

Facsimile instruments

In the early 1990s, Mitchell agreed to loan the Partch instruments for an indefinite but extended time period to Dean Drummond, a former Los Angeles Partch associate based in New York. This proved to be both a sound and regrettable move that provided greater exposure for the instruments, while abruptly silencing San Diego’s widely acclaimed Harry Partch Ensemble.

“The tough thing about losing the Partch instruments for so long,” Thumm said, “is that a whole musical world disappeared, instantly. We lost that world, which was not only an integral part of San Diego but also part of our lives. It was devastating to us to suddenly have that world go away.

“With any other musical ensemble, be it a rock band or an orchestra, after the rehearsals or concerts, everybody takes their instruments home with them. So, it was really tough to lose the instruments and the rapport we had developed as a group of musicians. Harry looked at his instruments, and protected them, as if they were almost his children. So having them finally come back to San Diego after all these years is a real homecoming for us. And none of us are getting any younger.”

The instruments’ move to the East Coast in 1991 was well intended, at least in theory.

It afforded audiences more opportunity to experience Partch’s music on the instruments he created, not on the facsimile instruments played by Germany’s Ensemble Musikfabrik — which had Partch instrument copies built in 2012 and performed his epic “Delusion of the Fury” at Carnegie Hall in 2015 — or the Los Angeles-based PARTCH Ensemble, which built its own copies.

Both groups appear earnest in their desire to share Partch’s music, but neither have any direct connection to the composer or San Diego’s Harry Partch Ensemble. None of the members of Musikfabrik and Grammy Award-winning PARTCH worked or consulted with Partch or Mitchell to learn the exacting requirements of performing his work, the specific meaning and intention behind every note and musical gesture, or the very specific philosophy and impetus for each of his compositions and how they were to be performed.

“There are people out there having their way with Harry’s music in ways that aren’t right, and I’ll be damned if anyone is going to do that with his original instruments,” Szanto said.

“When Harry made them, they were not just instruments, but works of art as well. That is why it’s so important they are cared for and maintained for here for generations to come.”

Drummond, who was the director of the Harry Partch Institute at New Jersey’s Montclair State University, died in 2013. A year later, the instruments were moved to the University of Washington in Seattle, where Drummond associate Charles Corey became the curator of the instruments. He also became the director of a new Partch ensemble that was even more detached from the composer and San Diego’s Harry Partch Ensemble than the group Drummond had led on the East Coast.

In 2019, University of Washington administrators decided they no longer wanted to spend money to keep the Partch instruments, mirroring the actions of aesthetically challenged administrators at other universities that had previously housed the historic instruments.

Now, after languishing in storage in Seattle for the past five years, the instruments are finally back in San Diego to stay.

Szanto, 71, is eager to set a new chapter in motion for Partch’s legacy. He estimates at least a dozen former Harry Partch Ensemble members are still musically active, although not all of them are still in San Diego.

“It will be a matter of getting funding,” he said. “But once we take stock of the instruments — some of which are now nearly 100 years old — and make any necessary restorations, the next stage is to get a fully functional organization to oversee them.

“There is a validity to having duplicate instruments that could travel for people to experience in other parts of the world. And that can be a secondary goal after the time and love is put into restoring the original instruments. We want people to be able to come to see and hear these instruments because there is absolutely no substitute for the originals.”

©2024 The San Diego Union-Tribune. Visit sandiegouniontribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments