Entertainment

/ArcaMax

Joe Jonas drops hint over Camp Rock 3

Joe Jonas appears to have suggested Camp Rock 3 is on its way.

The Sucker singer, along with his Jonas Brothers bandmates and siblings Nick and Kevin Jonas, starred opposite Demi Lovato in the 2008 Disney movie and its 2010 follow-up Camp Rock 2: The Final Jam, and he's suggested a script has been written for a third installment in the series, ...Read more

Zoe Kravitz and Lisa Bonet lost snake in Taylor Swift's house

Zoe Kravitz and her mom almost lost their pet snake in Taylor Swift's house.

The Big Little Lies actress and Lisa Bonet were staying at her friend's home amid the Los Angeles wildfires earlier this year when they got into a "little bit of a pickle" after the 57-year-old model's beloved reptile Orpheus slithered its way into a tiny hole in the ...Read more

Dolly Parton gives advice to Kelly Clarkson after Brandon Blackstock death

Dolly Parton has urged Kelly Clarkson to "remember the very best" of her time with Brandon Blackstock.

The 79-year-old music icon has offered some advice to her friends Kelly and Reba McEntire following the death of Blackstock - who was Kelly's ex-husband and Reba's stepson - and touched on her own experiences with grief after her husband Carl ...Read more

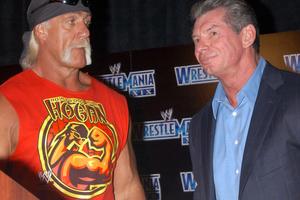

Ex WWE boss Vince McMahon says Hulk Hogan 'wasn't a racist' in very rare interview

Vince McMahon says Hulk Hogan "said some racist things" but "wasn't a racist".

The former WWE boss - who has given his first interview since resigning from the wrestling promotion's parent company TKO amid a lawsuit accusing him of sex trafficking and sexual assault - has reflected on the late world champion's 2015 scandal when he was heard ...Read more

Jimmy Kimmel obtains Italian citizenship

Jimmy Kimmel has obtained Italian citizenship.

The 57-year-old presenter - who has Katie, 33, and Kevin, 31, with ex-wife Gina Maddy and Jane, 11, and Billy, eight, with spouse Molly McNearney - has Italian heritage on his mother's side so sought to obtain official links to Europe because he is so unhappy with the state of the US under the ...Read more

Manny Jacinto recommends couples therapy

Manny Jacinto has advised all couples to get therapy.

The Freakier Friday actor tied the knot with Grey's Anatomy actress Dianne Doan and revealed the best piece of advice he was given prior to marriage, was to go to couples therapy "before you need it".

Manny, 37, told Cosmopolitan: "A good piece of advice that was given to me was to go to ...Read more

Reba McEntire pays tribute to Brandon Blackstock

Reba McEntire has paid tribute to her former stepson Brandon Blackstock following his death.

Brandon, 48, passed away last week after a secret three-year battle with melanoma and Reba - who was married to Brandon's father Narvel Blackstock from 1989 to 2015 - shared her grief in a comment on her son Shelby Blackstock's Instagram post.

Shelby -...Read more

Travis Kelce: 'I sort of made Taylor Swift a football fan'

Travis Kelce says he "made [Taylor Swift] a football fan".

The 35-year-old Kansas City Chiefs player has been dating pop superstar Taylor, 35, for two years and Travis revealed Taylor is now the "most engulfed fan" and even reads injury reports.

He told America's GQ: "I sort of made her a football fan. She is the most engulfed fan now. She ...Read more

Sean Avery and Hilary Rhoda reconcile

Sean Avery and Hilary Rhoda are back together.

The 45-year-old former pro ice hockey player and the 38-year-old model tied the knot in October 2015 and welcomed son Nash in 2020 but Hilary filed for divorce in July 2022 and a few months later, requested a temporary restraining order against him.

The restraining order became permanent in ...Read more

Johnny Depp to return to Pirates of the Caribbean franchise?

Johnny Depp could return for a new Pirates of the Caribbean movie.

Franchise producer Jerry Bruckheimer revealed work is currently being done on a new screenplay and he has spoken to Depp about reprising his role as Captain Jack Sparrow.

He told Entertainment Weekly: "If he likes the way the part's written, I think he would do it. It's all ...Read more

Chris O'Dowd to star in Artificial

Chris O'Dowd is set to star in Artificial.

According to The Hollywood Reporter, the Bridesmaids actor has joined the cast of Luca Guadagnino's comedic drama, which is reported to be a recounting of the rocky period at OpenAI in 2023 where CEO Sam Altman was fired and rehired in a matter of days.

Andrew Garfield, Cooper Koch, Yura Borisov, ...Read more

Jimmy Kimmel secures Italian citizenship in case he needs to escape during Trump's second term

Jimmy Kimmel revealed he has his Italian passport ready, just in case.

During an interview with comedian Sarah Silverman on her podcast, the “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” host discussed how “much worse” the president’s second term has been for the country, without getting into specifics. He said he has obtained Italian citizenship as a result....Read more

Review: South Korea-set 'Butterfly' packages family melodrama as an action-packed thriller

Thrillers, thrillers, thrillers, so many thrillers. Every third show I review seems to be one, and even if that math is not perfectly correct, the seeming is real enough. Sometimes they are full of interesting characters and ideas, sometimes full of posturing stereotypes with nothing to say, sometimes mostly smoke and noise, and often just take ...Read more

Jazz singer Sheila Jordan dies at 96

DETROIT — A jazz legend with a long, storied career and a global fan base, Detroit-born singer Sheila Jordan died on Monday in her home in New York City at the age of 96.

Named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 2012, Jordan is largely considered an underappreciated artist, considering her vocal talent and lengthy recording and ...Read more

Travis Kelce opens up about early stages of Taylor Swift romance

Travis Kelce says he and Taylor Swift are "just two people in love".

The 35-year-old NFL star opened up about the beginning of his relationship with pop superstar Taylor, 35, insisting that "it happened very organically".

Travis - who first spoke about his crush on Taylor on his New Heights podcast in 2023 - told America's GQ magazine: "...Read more

Angelina Jolie planning to leave LA

Angelina Jolie is planning to leave Los Angeles.

The 50-year-old actress - who shares custody of her children with former husband Brad Pitt - is set to be looking at putting "the house up for sale" and moving abroad next year when her youngest children, twins Knox and Vivienne, turn 18.

A source told PEOPLE: "Angelina never wanted to live in ...Read more

What to stream: Choose a Kurosawa original or one of many remakes

For his latest film “Highest 2 Lowest,” Spike Lee has turned to one of his influences, and one of cinema's most iconic filmmakers, Akira Kurosawa, remaking his 1963 film “High and Low.” Kurosawa’s films have been remade almost as long as he’s been making movies, so “Highest 2 Lowest” enters a pantheon of Kurosawa remakes that go ...Read more

Miriam Margolyes doesn't fear being cancelled

Miriam Margolyes doesn't worry about being cancelled.

The 84-year-old actress has faced a backlash for her criticism of the Israeli government's actions in Gaza but she believes she has a responsibility to speak out and try to instigate change, and she doesn't worry about the consequences for her career.

She told The Guardian newspaper: "...Read more

Cate Blanchett 'wildly interested' in English-language Squid Game

Cate Blanchett is "wildly open" to leading an English-language take on Squid Game.

The 56-year-old actress made a surprise appearance in the third series of the South Korean series as an unnamed American recruiter and she aditted she would love to take the role further.

Asked if she is interested in an English-language Squid Game sequel or ...Read more

Chris Hemsworth didn't find playing drums easy

Chris Hemsworth struggled to get to grips with the "very basics" of drumming ahead of his performance with Ed Sheeran.

The Thor actor joined the Bad Habits hitmaker on stage at a concert in Bucharest, Romania to play Thinking Out Loud in front of 70,000 fans last August for his Limitless: Live Better Now series but footage from the National ...Read more