Matthew Brooker: Oasis ticket surge pricing spurs misplaced fury

Published in Entertainment News

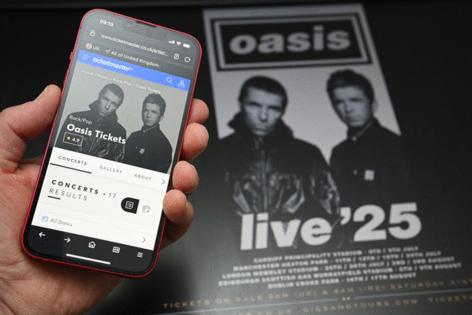

The use of "dynamic pricing" to sell tickets for the first Oasis concerts in 16 years has mired the British band's heralded reunion in controversy before it’s even begun. Fans waited for hours on Live Nation Entertainment Inc.’s Ticketmaster site at the weekend, only to see prices jump by multiples by the time they came to pay, prompting hundreds of complaints to advertising regulators, outrage from members of parliament and even the promise of a government probe. Some of the ire is misdirected.

We’ve heard this tune before. Taylor Swift and Bruce Springsteen are among artists who have run into similar furors in the U.S., where flexible ticket pricing has a longer history. In the U.K., the sale of Harry Styles tickets using the method attracted criticism in 2022. The Oasis affair brings the issue to a different level of public attention, though.

The Britpop band’s reunion tour will be one of the cultural events of 2025, at least among those who pine for the 1990s — a distant era when the U.K. was a more optimistic country and the economy was in great shape. An estimated 14 million people were expected to seek tickets, according to British press reports. Mess with that demographic at your peril. It clearly includes a number of the current parliamentary intake. “Scandalous,” “depressing” and “definitely cause for an investigation” were among members’ comments published Monday.

Lucy Powell, a Labour minister who is leader of the House of Commons, said she paid more than double the initial quoted cost for an Oasis ticket. Powell told BBC radio she didn’t “particularly like” surge pricing, before adding: “It is the market and how it operates.”

Precisely. Anyone who waited hours on the Ticketmaster site for a 148.50 pound ($195) ticket, only to be presented with a checkout price of more than 350 pounds ($458), has good reason to be irritated. But the advantage of a flexible pricing system is that it equalizes supply and demand. Tickets end up in the hands of those who value them most, in money terms. In economic terms, it’s a more efficient allocation of resources.

This can get obscured. Dynamic pricing has been around for a long time and is widely used for everything from ride-hailing and flights to hotel rooms. It has even spread to restaurants and beer. That hasn’t made it any more popular. An image of price-gouging attaches to the practice, perhaps because the most memorable examples tend to be negative — such as Uber prices jumping by multiple times as people tried to escape the London Bridge area after a 2017 terrorist attack in the U.K. capital. Examples of companies lowering prices at times of low demand are more easily forgotten. After all, humans are more averse to losses than they are pleased by gains.

Consider the position of a concert promoter. Pitch the cost of a ticket too high, and you might end up with half-empty arenas. Go too low and touts, or scalpers, will rush in and resell at a profit in the secondary market. They capture the excess value that would otherwise have gone to the artist and promoter. Dynamic pricing enables musicians to retain more of that surplus, which is the argument advanced by Ticketmaster and others for using the mechanism (ticketing platforms that earn a percentage also benefit from higher prices, of course).

The U.K. reaction betrays some muddled thinking. The government will examine dynamic pricing as part of a upcoming consultation into the ticketing market that’s aimed primarily at tackling scalpers. Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy said the government plans to end the “scourge” of touts and ensure tickets “at fair prices.”

But who decides what a “fair” price is? The implication is that the prices set by the Ticketmaster algorithm were too high, but the evidence for that is dubious. The cheapest ticket for Oasis’s July 25 date at Wembley Stadium in London was 740 pounds ($969) on secondary-sales site Viagogo as of Monday morning, or more than double the 350 pound Ticketmaster cost that caused outrage. That’s a clear sign that some money was left on the table. Forcing sellers to set a lower price by fiat would only hand more profit to scalpers (which few governments or consumers like but no one has found an effective way to eradicate).

That’s not to say that any ticketing system is perfect or beyond scrutiny. If you’re going to spend 11 hours waiting for your dream gig ticket, you’d at least want to know that the price may have doubled by the time you get to the front of the line. This seems to have come as a surprise to many. Companies that use dynamic pricing need to be transparent about it, though “people can always choose not to buy,” Oded Koenigsberg, a professor of marketing at London Business School, told me.

There’s also a social-equity argument here. What if the market-clearing price is more than some of the band’s core fan base can afford? That’s an especial irony for Oasis, whose image leans heavily on the band’s working-class Manchester roots (guitarist Noel Gallagher complained in 2022 that rock music had become too middle class).

Charging what the market will bear isn’t always the wisest strategy, at least for companies that want to retain consumer loyalty. Uber Technologies Inc. cancelled surge pricing on the night of the 2017 attack and refunded customers who had paid the higher prices.

Such considerations may count for less with rock icons, who can usually count on the devotion of followers. Oasis could surely do something for its priced-out fans if it chose, though. It’s an appeal that makes more sense than railing against a pricing mechanism.

———

(Matthew Brooker is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business and infrastructure. Formerly, he was an editor for Bloomberg News and the South China Morning Post.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments